Times Higher Education World University Rankings

It also has begun publishing three regional tables for universities in Asia, Latin America, and BRICS and emerging economies, which are ranked with separate criteria and weightings.

[8] Commenting on Times Higher Education's decision to split from QS, former editor Ann Mroz said, "universities deserve a rigorous, robust and transparent set of rankings – a serious tool for the sector, not just an annual curiosity."

She went on to explain the reason behind the decision to continue to produce rankings without QS' involvement, saying that: "The responsibility weighs heavy on our shoulders...we feel we have a duty to improve how we compile them.

"[9] Phil Baty, editor of the new Times Higher Education World University Rankings, admitted in Inside Higher Ed, "The rankings of the world's top universities that my magazine has been publishing for the past six years, and which have attracted enormous global attention, are not good enough.

In fact, the surveys of reputation, which made up 40 percent of scores and which Times Higher Education until recently defended, had serious weaknesses.

"[10] He went on to describe previous attempts at peer review as "embarrassing" in The Australian: "The sample was simply too small, and the weighting too high, to be taken seriously.

[13][14][15] The Globe and Mail in that year also described the Times Higher Education World University Rankings to be "arguably the most influential.

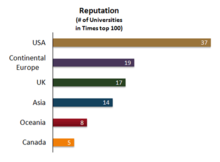

The survey gathered 13,388 responses among scholars who, according to THE, were "statistically representative of global higher education's geographical and subject mix.

The magazine stated that it used this data as "proxy for high-quality knowledge transfer" and planned to add more indicators for the category in future years.

Phil Baty wrote that this was in the "interests of fairness," because "the lower down the tables you go, the more the data bunch up and the less meaningful the differentials between institutions become."

[5] Steve Smith, president of Universities UK, praised the new methodology as being "less heavily weighted towards subjective assessments of reputation and uses more robust citation measures," which "bolsters confidence in the evaluation method.

"[30] David Willetts, British Minister of State for Universities and Science praised the rankings, noting that "reputation counts for less this time, and the weight accorded to quality in teaching and learning is greater.

"[31] In 2014, David Willetts became chair of the TES Global Advisory Board, responsible for providing strategic advice to Times Higher Education.

Citations as a metric for effective education is problematic in many ways, placing universities who do not use English as their primary language at a disadvantage.

[35] A second important disadvantage for universities of non-English tradition is that within the disciplines of social sciences and humanities the main tool for publications are books which are not or only rarely covered by digital citations records.

[39] In January 2010, THE concluded the method employed by Quacquarelli Symonds, who conducted the survey on their behalf, was flawed in such a way that bias was introduced against certain institutions, including LSE.

[40] A representative of Thomson Reuters, THE's new partner, commented on the controversy: "LSE stood at only 67th in the last Times Higher Education-QS World University Rankings – some mistake surely?

[45] The discovery resulted in an investigation by THE and the provision of guidance to the university on the submission of data,[45] however, it also led to the criticism amongst faculty members of the ease with which THE's ranking system could be abused.

[46] Seven Indian Institutes of Technology (Mumbai, Delhi, Kanpur, Guwahati, Madras, Roorkee and Kharagpur) have boycotted THE rankings from 2020.