Titration

A reagent, termed the titrant or titrator,[2] is prepared as a standard solution of known concentration and volume.

Tiltre became titre,[4] which thus came to mean the "fineness of alloyed gold",[5] and then the "concentration of a substance in a given sample".

[6] In 1828, the French chemist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac first used titre as a verb (titrer), meaning "to determine the concentration of a substance in a given sample".

French chemist François-Antoine-Henri Descroizilles (fr) developed the first burette (which was similar to a graduated cylinder) in 1791.

[12][13][14][15] A major improvement of the method and popularization of volumetric analysis was due to Karl Friedrich Mohr, who redesigned the burette into a simple and convenient form, and who wrote the first textbook on the topic, Lehrbuch der chemisch-analytischen Titrirmethode (Textbook of analytical chemistry titration methods), published in 1855.

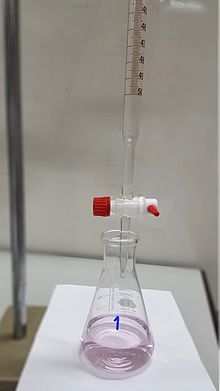

[16][17] A typical titration begins with a beaker or Erlenmeyer flask containing a very precise amount of the analyte and a small amount of indicator (such as phenolphthalein) placed underneath a calibrated burette or chemistry pipetting syringe containing the titrant.

Typical titrations require titrant and analyte to be in a liquid (solution) form.

[20] In instances where two reactants in a sample may react with the titrant and only one is the desired analyte, a separate masking solution may be added to the reaction chamber which eliminates the effect of the unwanted ion.

For instance, the oxidation of some oxalate solutions requires heating to 60 °C (140 °F) to maintain a reasonable rate of reaction.

For very strong bases, such as organolithium reagent, metal amides, and hydrides, water is generally not a suitable solvent and indicators whose pKa are in the range of aqueous pH changes are of little use.

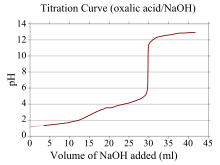

When the number of moles of bases added equals the number of moles of initial acid or so called equivalence point, one of hydrolysis and the pH is calculated in the same way that the conjugate bases of the acid titrated was calculated.

A potentiometer or a redox indicator is usually used to determine the endpoint of the titration, as when one of the constituents is the oxidizing agent potassium dichromate.

The color change of the solution from orange to green is not definite, therefore an indicator such as sodium diphenylamine is used.

[31] Analysis of wines for sulfur dioxide requires iodine as an oxidizing agent.

In this case, starch is used as an indicator; a blue starch-iodine complex is formed in the presence of excess iodine, signalling the endpoint.

[33] In iodometry, at sufficiently large concentrations, the disappearance of the deep red-brown triiodide ion can itself be used as an endpoint, though at lower concentrations sensitivity is improved by adding starch indicator, which forms an intensely blue complex with triiodide.

In one common gas phase titration, gaseous ozone is titrated with nitrogen oxide according to the reaction After the reaction is complete, the remaining titrant and product are quantified (e.g., by Fourier transform spectroscopy) (FT-IR); this is used to determine the amount of analyte in the original sample.

Second, the measurement does not depend on a linear change in absorbance as a function of analyte concentration as defined by the Beer–Lambert law.

In general, they require specialized complexometric indicators that form weak complexes with the analyte.

[38] One of the uses is to determine the iso-electric point when surface charge becomes zero, achieved by changing the pH or adding surfactant.

[39] An assay is a type of biological titration used to determine the concentration of a virus or bacterium.

The positive or negative value may be determined by inspecting the infected cells visually under a microscope or by an immunoenzymetric method such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Equivalence point is the theoretical completion of the reaction: the volume of added titrant at which the number of moles of titrant is equal to the number of moles of analyte, or some multiple thereof (as in polyprotic acids).

Endpoint is what is actually measured, a physical change in the solution as determined by an indicator or an instrument mentioned above.

Identifying the pH associated with any stage in the titration process is relatively simple for monoprotic acids and bases.

Graphical methods,[45] such as the equiligraph,[46] have long been used to account for the interaction of coupled equilibria.