Aztec warfare

The Aztec armed forces were typically made up of a small number people ranging from 10-15 people of commoners (yāōquīzqueh [jaː.oːˈkiːskeʔ], "those who have gone to war") who possessed extensive military training, and a smaller but still considerable number of highly professional warriors belonging to the nobility (pīpiltin [piːˈpiɬtin]) and who were organized into warrior societies and ranked according to their achievements.

The first was sacrificing the firstborn: the subjugation of enemy city states (Altepetl) in order to exact tribute and expand Aztec political hegemony.

The first action of a ruler elect was always to stage a military campaign which served the dual purpose of showing his ability as a warrior and thus make it clear to subject polities that his rule would be as tough on any rebellious conduct as that of his predecessor, and to provide abundant captives for his coronation ceremony.

Friar Diego Durán and the chronicles based on the Crónica X states that the Xochiyaoyotl was instigated by Tlacaelel during the great Mesoamerican famine of 1450–1454 under the reign of Moctezuma I.

These sources state that Tlacaelel arranged with the leaders of Tlaxcala, Cholula, and Huexotzinco, and Tliliuhquitepec to engage in ritual battles that would provide all parties with enough sacrificial victims to appease the gods.

Ross Hassig (1988) however poses four main political purposes of xochiyaoyotl: Since all boys starting at age 15 were trained to become warriors, Aztec society as a whole had no standing army.

Especially in the latter case, they would also become full-time warriors working for the city-state to protect merchants and the city itself, and resembled the police force of Aztec society.

Prominent examples are the strongholds at Oztuma (Oztōmān [osˈtoːmaːn]) where the Aztecs built a garrison to keep the rebellious Chontales in line; in Quauhquechollan (modern-day Huauquechula) near Atlixco where the Aztecs built a garrison in order to always have forces close to their traditional enemies the Tlaxcalteca, Chololteca and Huexotzinca; and in Malinalco near Toluca.

The latter is where Ahuitzotl built garrisons and fortifications to keep watch over the Matlatzinca, Mazahua and Otomies and to always have troops close to the enemy Tarascan statethe borders with which were also guarded and at least partly fortified on both sides.

The commoners were organized into "wards" (calpōlli) [kaɬˈpoːlːi] that were under the leadership of tiachcahuan [tiat͡ʃˈkawaːn] ("leaders") and calpoleque [kalpoːleʔkeʔ] ("calpulli owners").

The adjacent image shows the Tlacateccatl and the Tlacochcalcatl and two other officers (probably priests) known as Huitznahuatl and Ticocyahuacatl, all dressed in their tlahuiztli suits.

[12] When formal training in handling weapons began at age fifteen, youth would begin to accompany the seasoned warriors on campaigns so that they could become accustomed to military life and lose the fear of battle.

The members of the Aztec army had loyalties to many different people and institutions, and ranking was not based solely on the position one held in a centralized military hierarchy.

Also of great importance was the communication of messages between the military leaders and the warriors on the field so that political initiatives and collaborative ties could be established and maintained.

As they traveled throughout the empire and beyond to trade with groups outside the Aztec's control, the king would often request that the pochteca return from their route with both general and specific information.

General information, such as the perceived political climate of the areas traded in, could allow the king to gauge what actions might be necessary to prevent invasions and keep hostility from culminating in large-scale rebellion.

If the caravan was likely to pass through dangerous territory, Aztec warriors accompanied the travelers to provide much-needed protection from wild animals and rival cultures.

The Aztecs used a system in which men stationed approximately 4.2 kilometres (2.6 mi) apart along main roads relayed messages from the empire to armies in the field or to distant cities and vice versa.

Due to the extremely dangerous nature of this job (they risked a torturous death and the enslavement of their family if discovered), these spies were amply compensated for their work.

Warriors at the front lines of the army would carry the ahtlatl and about three to five tlacochtli, and would launch them after the waves of arrows and sling projectiles as they advanced into battle before engaging into melee combat.

The Aztecs used oval shaped rocks or hand molded clay balls filled with obsidian flakes or pebbles as projectiles for this weapon.

Bernal Diaz del Castillo noted that the hail of stones flung by Aztec slingers was so furious that even well armored Spanish soldiers were wounded.

The darts used for this weapon were made out of sharpened wood fletched with cotton and usually doused in the neurotoxic secretions from the skin of tree frogs found in jungle areas of central Mexico.

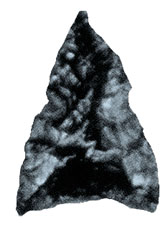

Essentially a wooden sword with sharp obsidian blades embedded into its sides (similar in appearance and build to a modern cricket bat).

A dagger with a double sided blade made out of flint or obsidian with an elaborate stone or wooden handle, 7 to 9 inches (18 to 23 cm) overall in length.

Usually made to work as a single piece of clothing with an opening in the back, they covered the entire torso and most of the extremities of a warrior, and offered added protection to the wearer.

Then the warriors advanced into melee combat and during this phase, the atlatl was used – this missile weapon was more effective over shorter distances than slings and bows, and much more lethal.

Youths participating in battle for the first time would usually not be allowed to fight before the Aztec victory was ensured, after which they would try to capture prisoners from the fleeing enemy.

I saw one of them defend himself courageously against two swift horses, and another against three and four, and when the Spanish horseman could not kill him one of the horsemen in desperation hurled his lance, which the Aztec caught in the air, and fought with him for more than an hour until two-foot soldiers approached and wounded him with two or three arrows.

The mourners would not bathe and groom themselves for eighty days, believing this allowed time for the fallen warrior's soul to reach the Sky of the Sun.