Tobacco Protest

[4] On 20 March 1890, Emperor Naser al-Din granted a concession to Major G. F. Talbot for a full monopoly over the production, sale, and export of tobacco for fifty years.

[8] In September 1890, the first resounding protest against the concession manifested, however it did not emerge from the Persian merchant class or ulama but rather from the Russian government who stated that the Tobacco Régie violated freedom of trade in the region as stipulated by the Treaty of Turkmanchai.

In February 1891, Major G. F. Talbot traveled to Iran to install the Tobacco Régie, and soon thereafter, the Emperor made news of the concession public for the first time, sparking immediate disapproval throughout the country.

Despite the rising tensions, director of the Tobacco Régie Julius Ornstein arrived in Tehran in April and was assured by Prime Minister Amin al-Sultan that the concession had the full support of the House of Qajar.

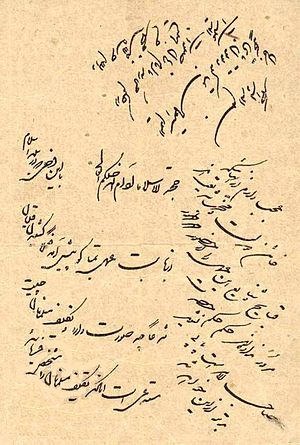

[10] In the meantime, anonymous letters were being sent to high members of the government while placards were circulating in cities such as Tehran and Tabriz, both displaying public anger towards the granting of concessions to foreigners.

[12] The ulama proved to be a highly valuable ally of the bazaaris as key religious leaders sought to protect national interests from foreign domination.

Since the Safavid conversion of Iran to Shia Islam after 1501, the ulama played a paramount role in society – they ran religious schools, maintained the charity of endowments, acted as arbiters and judges, and were seen as the intermediaries between God and Muslims in the country.

[14] Finally, as the clergy pointed out, the concession directly contradicted sharia, because individuals were not allowed to purchase or sell tobacco of their own free will and were unable to go elsewhere for business.

[16] In Isfahan, a boycott of the consumption of tobacco was implemented even before Shirazi's fatwa, while in the city of Tabriz, the bazaar closed down and the ulama stopped teaching in the madrasas.

As the tobacco boycott grew larger, Naser al-Din Shah and Prime Minister Amin al-Sultan found themselves powerless to stop the popular movement fearing Russian intervention in case a civil war materialized.

"[22] Despite the popularity of tobacco, the religious ban was so successful that it was said that women in the Qajar harem quit smoking and his servants refused to prepare his water pipe.

"[19] The fatwa has been called a "stunning" demonstration of the power of the marja'-i taqlid, and the protest itself has been cited as one of the issues that led to the Persian Constitutional Revolution a few years later.

Following the cancellation of the concession, there were still difficulties between the Qajar government and the Imperial Tobacco Corporation of Persia in terms of negotiating the amount of compensation that would be paid to the company.