Toda people

Toda people are a Dravidian ethnic group who live in the State of Tamil Nadu in southern India.

Before the 18th century and British colonisation, the Toda coexisted locally with other ethnic communities, including the Kota, Badaga and Kurumba.

Although an insignificant fraction of the large population of India, since the early 19th century the Toda have attracted "a most disproportionate amount of attention from anthropologists and other scholars because of their ethnological aberrancy" and "their unlikeness to their neighbours in appearance, manners, and customs".

[3] The study of their culture by anthropologists and linguists proved significant in developing the fields of social anthropology and ethnomusicology.

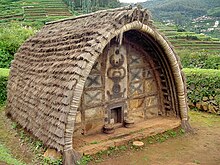

The Toda traditionally live in settlements called mund, consisting of three to seven small thatched houses, constructed in the shape of half-barrels and located across the slopes of the pasture, on which they keep domestic buffalo.

Their economy was pastoral, based on the buffalo, whose dairy products they traded with neighbouring peoples of the Nilgiri Hills.

Toda religion features the sacred buffalo; consequently, rituals are performed for all dairy activities as well as for the ordination of dairymen-priests.

The religious and funerary rites provide the social context in which complex poetic songs about the cult of the buffalo are composed and chanted.

[4] Fraternal polyandry in traditional Toda society was fairly common; however, this practice has now been totally abandoned, as has female infanticide.

During the last quarter of the 20th century, some Toda pasture land was lost due to outsiders using it for agriculture[4] or afforestation by the State Government of Tamil Nadu.

Another factor in the uncertainty in the figures is the declared or undeclared inclusion or exclusion of Christian Todas by the various enumerators ...

This sliding door is placed inside the hut, and is arranged and fixed on two stout stakes, as to be easily moved back and forth.

The front portion of the hut is decorated with the Toda art forms, a kind of rock mural painting.

[13] According to the Toda religion, Ön and his wife Pinârkûrs went to a part of the Nilgiri hills, known as the Kundahs, and set up an iron bar from one end to the other.

Due to the celebratory nature of Toda funerals, outsiders are typically invited to participate in the festivities.

Diviners work in pairs and explain misfortunes that have occurred in the Toda villages like the burning down of a dairy.

According to Sir James Frazer in 1922 (see quote below from Golden Bough), the holy milkman was prohibited from walking across bridges while in office.

Linguists have classified Toda (along with its neighbour Kota) as a member of the southern subgroup of the historical family proto-South-Dravidian.

In modern linguistic terms, the aberration of Toda results from a disproportionately high number of syntactic and morphological rules, of both early and recent derivation, which are not found in the other South Dravidian languages (save Kota, to a small extent.

[23] Registrar of Geographical Indication gave GI status for this unique embroidery, a practice which has been passed on to generations.

The status ensures uniform pricing for Toda embroidery products and provides protection against low-quality duplication of the art.

[24] Toda's quaint barrel vaulted houses, which symbolise the Nilgiris, are today hard to spot.