Kannada

[26][better source needed] Kannada, like Malayalam and Tamil, is a South Dravidian language and a descendant of Tamil-Kannada, from which it derives its grammar and core vocabulary.

[36] Iravatam Mahadevan, author of a work on early Tamil epigraphy, argued that oral traditions in Kannada and Telugu existed much before written documents were produced.

He can be quoted as follows:[37] If proof were needed to show that Kannada was the spoken language of the region during the early period, one needs only to study the large number of Kannada personal names and place names in the early Prakrit inscriptions on stone and copper in Upper South India [...] Kannada was spoken by relatively large and well-settled populations, living in well-organised states ruled by able dynasties like the Satavahanas, with a high degree of civilisation [...] There is, therefore, no reason to believe that these languages had less rich or less expressive oral traditions than Tamil had towards the end of its pre-literate period.The Ashoka rock edict found at Brahmagiri (dated to 250 BC) has been suggested to contain words (Isila, meaning to throw, viz.

[41] Pliny the Elder, a Roman historian, wrote about pirates between Muziris and Nitrias (Netravati River), called Nitran by Ptolemy.

[42][43][44] The Greek geographer Ptolemy (150 AD) mentions places such as Badiamaioi (Badami), Inde (Indi), Kalligeris (Kalkeri), Modogoulla (Mudagal), Petrigala (Pattadakal), Hippokoura (Huvina Hipparagi), Nagarouris (Nagur), Tabaso (Tavasi), Tiripangalida (Gadahinglai), Soubouttou or Sabatha (Savadi), Banaouase (Banavasi), Thogorum (Tagara), Biathana (Paithan), Sirimalaga (Malkhed), Aloe (Ellapur) and Pasage (Palasige).

[45] He mentions a Satavahana king Sire Polemaios, who is identified with Sri Pulumayi (or Pulumavi), whose name is derived from the Kannada word for Puli, meaning tiger.

Nagarouris (Nagur), Tabaso (Tavasi), Inde (Indi), Tiripangalida (Gadhinglaj), Hippokoura (Huvina Hipparagi), Soubouttou (Savadi), Sirimalaga (Malkhed), Kalligeris (Kalkeri), Modogoulla (Mudgal), and Petirgala (Pattadakal)—as being located in Northern Karnataka, which explain the existence of Kannada place names (and the language and culture) in the southern Kuntala region during the reign of Vasishtiputra Pulumayi (c. 85–125 AD, i.e., late 1st century – early 2nd century AD) who was ruling from Paithan in the north and his son, prince Vilivaya-kura or Pulumayi Kumara was ruling from Huvina Hipparagi in present Karnataka in the south.

[47] An early ancestor of Kannada (or a related language) may have been spoken by Indian traders in Roman-era Egypt and it may account for the Indian-language passages in the ancient Greek play known as the Charition mime.

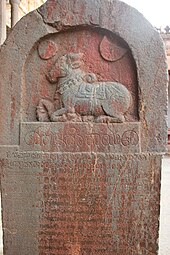

[49][50][51][52] A set of five copper plate inscriptions discovered in Mudiyanur, though in the Sanskrit language, is in the Pre-Old Kannada script older than the Halmidi edict date of 450 AD, as per palaeographers.

Followed by B. L. Rice, leading epigrapher and historian, K. R. Narasimhan following a detailed study and comparison, declared that the plates belong to the 4th century, i.e., 338 AD.

[64][65] Current estimates of the total number of existing epigraphs written in Kannada range from 25,000 by the scholar Sheldon Pollock to over 30,000 by Amaresh Datta of the Sahitya Akademi.

The book makes reference to Kannada works by early writers such as King Durvinita of the 6th century and Ravikirti, the author of the Aihole record of 636 AD.

[88] Some early writers of prose and verse mentioned in the Kavirajamarga, numbering 8–10, stating these are but a few of many, but whose works are lost, are Vimala or Vimalachandra (c. 777), Udaya, Nagarjuna, Jayabandhu, Durvinita (6th century), and poets including Kaviswara, Srivijaya, Pandita, Chandra, Ravi Kirti (c. 634) and Lokapala.

"Kavirajamarga" also discusses earlier composition forms peculiar to Kannada, the "gadyakatha", a mixture of prose and poetry, the "chattana" and the "bedande", poems of several stanzas that were meant to be sung with the optional use of a musical instrument.

Early Kannada writers regularly mention three poets as of especial eminence among their predecessors – Samanta-bhadra, Kavi Parameshthi and Pujyapada.

[97] Other writers, whose works are not extant now but titles of which are known from independent references such as Indranandi's "Srutavatara", Devachandra's "Rajavalikathe",[91] Bhattakalanka's "Sabdanusasana" of 1604,[85] writings of Jayakirthi[102] are Syamakundacharya (650), who authored the "Prabhrita", and Srivaradhadeva (also called Tumubuluracharya, 650 or earlier), who wrote the "Chudamani" ("Crest Jewel"), a 96,000-verse commentary on logic.

[85][93][101][103] The Karnateshwara Katha, a eulogy for King Pulakesi II, is said to have belonged to the 7th century;[102] the Gajastaka, a lost "ashtaka" (eight line verse) composition and a work on elephant management by King Shivamara II, belonged to the 8th century,[104] this served as the basis for 2 popular folk songs Ovanige and Onakevadu, which were sung either while pounding corn or to entice wild elephants into a pit ("Ovam").

[107] During the 9th century period, the Digambara Jain poet Asaga (or Asoka) authored, among other writings, "Karnata Kumarasambhava Kavya" and "Varadamana Charitra".

[91][104] Jinachandra, who is referred to by Sri Ponna (c. 950 AD) as the author of "Pujyapada Charita", had earned the honorific "modern Samantha Bhadra".

[112] The Vachana Sahitya tradition of the 12th century is purely native and unique in world literature, and the sum of contributions by all sections of society.

More importantly, they held a mirror to the seed of social revolution, which caused a radical re-examination of the ideas of caste, creed and religion.

[143] The Golars or Golkars are a nomadic herdsmen tribe present in Nagpur, Chanda, Bhandara, Seoni and Balaghat districts of Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh speak the Golari dialect of Kannada, which is identical to the Holiya dialect spoken by their tribal offshoot Holiyas present in Seoni, Nagpur and Bhandara of Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra.

Matthew A. Sherring describes the Golars and Holars as a pastoral tribe from the Godavari banks established in the districts around Nagpur, in the stony tracts of Ambagarh, forests around Ramplee and Sahangadhee.

[144] The Kurumvars of Chanda district of Maharashtra, a wild pastoral tribe, 2,200 in number as per the 1901 census, spoke a Kannada dialect called Kurumvari.

The Kurumbas or Kurubas, a nomadic shepherd tribe were spread across the Nilgiris, Coimbatore, Salem, North and South Arcots, Trichinopoly, Tanjore and Pudukottai of Tamil Nadu, Cuddapah and Anantapur of Andhra Pradesh, Malabar and Cochin of Kerala and South Canara and Coorg of Karnataka and spoke the Kurumba Kannada dialect.

[156] While an early account of Kannada's grammar is available in Shabdamanidarpana, it has played a central role in the modern linguistics thanks to its unique semantic and syntactic properties that have been significant to studies of language acquisition and innateness.

[157] This was significant, because it allowed him to test whether an observation of English-learning infants, that they worked out novel verb meanings based on the number of overt NPs they took, applied cross-linguistically.

[158] This has been used by generativists and UG nativists to argue that verb meaning acquisition based on syntactic bootstrapping is language universal and innate.

[157] The second property of major significance to develops in modern linguistic understandings lies in the fact that in Kannada negation comes at the end of the sentence and the quantified object linearly precedes it.

[159] This has been used to argue that infants universally represent sentences not as mere strings of adjacent words, but as hierarchical objects, a regular talking point among Chomskyans and nativists.