Tolkien's modern sources

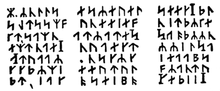

Tolkien appears to have made use, too, of early science fiction, such as H. G. Wells's subterranean Morlocks from the 1895 The Time Machine and Jules Verne's hidden runic message in his 1864 Journey to the Center of the Earth.

[3] Tolkien wrote that stories about "Red Indians" were his favourites as a boy; Shippey likens the Fellowship's trip downriver, from Lothlórien to Tol Brandir "with its canoes and portages", to James Fenimore Cooper's 1826 historical romance The Last of the Mohicans.

[9] Shippey writes that in the Eastemnet, Éomer's riders of Rohan circle "round the strangers, weapons poised" in a scene "more like the old movies' image of the Comanche or the Cheyenne than anything from English history".

[10] When interviewed in 1966, the only book Tolkien named as a favourite was Haggard's 1887 adventure novel She: "I suppose as a boy She interested me as much as anything—like the Greek shard of Amyntas [Amenartas], which was the kind of machine by which everything got moving.

It was (apparently) that of a woman of great age, so shrunken that in size it was no larger than that of a year-old child, and was made up of a collection of deep yellow wrinkles ... a pair of large black eyes, still full of fire and intelligence, which gleamed and played under the snow-white eyebrows, and the projecting parchment-coloured skull, like jewels in a charnel-house.

"[16] Tolkien wrote of being impressed as a boy by Samuel Rutherford Crockett's 1899 historical fantasy novel The Black Douglas and of using its fight with werewolves for the battle with the wargs in The Fellowship of the Ring.

[3] Parallels between The Hobbit and Jules Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth include a hidden runic message and a celestial alignment that direct the adventurers to the goals of their quests.

Tolkien wished to imitate the style and content of Morris's medievalising prose and poetry romances such as the 1889 The House of the Wolfings,[T 6] and made use of placenames such as the Dead Marshes[T 7] and Mirkwood.

[23] The medievalist Marjorie Burns writes that Bilbo Baggins's character and adventures in The Hobbit match Morris's account of his travels in Iceland in the early 1870s in numerous details.

He meets a "boisterous" Beorn-like man called "Biorn the boaster" who lives in a hall beside Eyja-fell, and who tells Morris, tapping him on the belly, "... besides, you know you are so fat", just as Beorn pokes Bilbo "most disrespectfully" and compares him to a plump rabbit.

Burns suggests that these images "make excellent models" for the Bilbo who runs puffing to the Green Dragon inn or "jogs along behind Gandalf and the dwarves" on his quest.

[34] The scholar of English literature Anna Vaninskaya argues that the form and themes of Tolkien's early writings fit into the romantic tradition of writers like Morris and W. B. Yeats.

[35] Postwar literary figures such as Anthony Burgess, Edwin Muir and Philip Toynbee heavily criticized The Lord of the Rings, but others like the novelists Naomi Mitchison and Iris Murdoch respected the work, while the poet W. H. Auden championed it.

[2] Ordway notes that Tolkien remained interested in Joseph Henry Shorthouse's "strange, long-forgotten" 1881 novel John Inglesant, and suggests that its "moral conflict and competing loyalties" and its "providentially freeing climax consequent upon the exercise of pity" are reflected in "perhaps the key theme" of The Lord of the Rings.

[36] Thomas Kullmann and Dirk Siepmann state that aspects of Tolkien's prose style and language in The Lord of the Rings are comparable with that of nineteenth and twentieth century novelists, giving multiple examples.