Tom Johnson (bareknuckle boxer)

His dissipation outside the ring appears to have resulted in his decision to leave England for Ireland, where he continued to tutor other boxers but eventually resorted to gambling to earn a living.

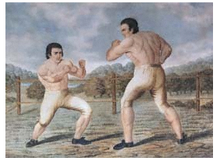

Prizefighting in early 18th-century England took many forms rather than just pugilism, which was referred to by noted swordsman and then boxing champion James Figg as "the noble science of defence".

[8] The appeal of prizefighting at that time has been compared to that of duelling; historian Adrian Harvey says that: Patriotic writers often extolled the manly sports of the British, claiming that they reflected a courageous, robust, individualism in which the nation could take pride.

[9]From a legal standpoint prizefights ran the risk of being classified as disorderly assemblies, but in practice the authorities were mainly concerned about the number of criminals congregating there.

[9][11] This patronage also explains why London was the centre for the sport; people of wealth tended to congregate in the city during the winter months and in the summer dispersed to their country estates.

Brute strength was the primary factor for success and knock-downs were frequent, a consequence of the instability inherent in the positioning of the fighters' feet.

Moving around the ring, known as shifting, was deprecated and sometimes explicitly prohibited by the rules for a fight;[14] going to ground without being hit could lead to claims that the man still standing had won.

At that time Johnson had no intention of earning a living from the sport, but he became so goaded by a professional known as The Croydon Drover that a fight was arranged for March 1784, at Kennington Common.

[16] Johnson did not fight again until he beat Bill Love, a butcher, at Barnet on 11 or 13 January 1786 in a contest that lasted five minutes and offered a prize of 50 guineas.

[5][16][18] The final fight of Johnson's early period, during which the stake money was relatively low, was his comprehensive win over a ponderous fighter called Fry for a prize of 50 guineas at Kingston.

That writer also explained that he "worked round his antagonist in a way peculiar to himself, that so puzzled his adversary to find out his intent, that he was frequently thrown off his guard, by which manoeuvring Johnson often gained the most important advantages.

[14] Having exhausted challengers in London, he took on Bristolian professional Bill Warr for 200 guineas at Oakhampton, Berkshire on 18 January 1787, although the manner of his victory on this occasion was "scarcely worthy of being called a fight", according to The Sportsman's Magazine.

[5] Warr had to resort to shifting and falling to the ground in order to stay in the contest, and as both tactics were regarded as underhand he attracted the ire of the crowd.

[16][21][22][a] A hiatus in Johnson's boxing career followed, with no challengers coming forward until the Irish champion Michael Ryan took an interest.

The fight at Wraysbury,[23] then in Buckinghamshire, on either 18 or 19 December 1787 saw Richard Humphries ("The Gentleman Boxer") acting as Johnson's second and Daniel Mendoza as his bottle-holder.

Nor did they specify what should happen if a contestant fell to the ground, which is what Johnson did in order to avoid being hit – this action was thought by the spectators to be unsporting but was permitted by the two umpires.

Before long both fighters showed signs of their opponent's attacks, with first Perrins and then Johnson suffering cut eyes and then further damage to their faces.

[4][30][32][33] Tony Gee has said that Perrins had overwhelming physical advantages but, owing to his naïvety, no clause was inserted in the articles of agreement to prevent "shifting" ...

The event was recorded in The Gentleman's Magazine of that month: ... a great boxing match took place ... between two bruisers, Perrins and Johnson: for which a turf stage had been erected 5-foot 6 inches high, and about 40 feet square.

The combatants set-to at one in the afternoon; and, after sixty-two rounds of fair and hard fighting, victory was declared in favour of Johnson, exactly at fifteen minutes after two.

[37] Chaloner has speculated that these may have been produced by Perrins' employers, Boulton and Watt, and says that they bear similarities with the work of a French die maker called Ponthon who was supplying the firm with industrial items from at least 1791.

He had recovered from his previous illness and won a fight at Banbury against Jacombs, another of the Birmingham challengers, on the day after Johnson's victory against Perrins.

[26] Subsequently, Bryan had drawn a 180-round contest with Bill Hooper, also known as "The Tinman", regarding which The Sportsman's Magazine claimed "A more ridiculous match never took place in the annals of pugilism.

Egan speculated that Johnson's change in style, evident from the outset of the fight might have been due to either genuine concern about Bryan's abilities or from his gambling problems; either way, "there was a miserable falling off in him altogether!

He performed this duty for Tom Tyne ("The Tailor") at Croydon on 1 July 1788 and at Horton Moor on 24 March 1790,[44] having previously done so for a fighter called Savage who had taken on Jack Doyle at Stepney Fields on 22 November 1787.

[47] Similarly, he acted as second for Hooper when he fought George Maddox at Sydenham Common on 10 February 1794[48] and for Tom "Paddington" Jones at Blackheath on 10 May 1794.

[49] Other occasions when he acted as second include for John Jackson (near to Croydon, 9 June 1788; and against Mendoza at Hornchurch on 15 April 1795), and Joe Ward (at Hyde Park, date unknown).

Retired prizefighters at that time often received the proceeds of a financial collection from their supporters to enable them to buy a licence to operate such premises: "today's fighter was merely tomorrow's publican in waiting".

Most of these sporting "pubs" had a large room at the back or upstairs, which was open one night a week (preferably Saturday), for public sparring, which was always conducted by a pugilist of some note.

[4][26] Johnson moved to Copper Alley, Dublin, but had to leave after magistrates determined that his premises were "not proving so consonant to the principles of propriety, as was wished".