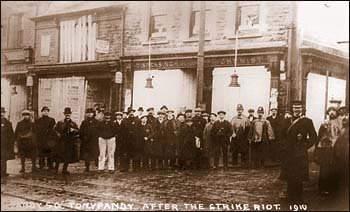

Tonypandy riots

[3] Historians such as Paul Addison however, argue that Churchill did his best to prevent violence; he promised miners that peaceful conduct would be rewarded with sympathetic arbitration.

After a short test period to determine what would be the future rate of extraction, owners claimed that the miners deliberately worked more slowly than possible.

[7]: [p175] On 1 September 1910, the owners posted a lock-out notice at the mine that closed the site to all 950 workers, not just the 70 at the newly opened Bute seam.

[7]: [p175] A conciliation board was formed to reach an agreement, with William Abraham acting on behalf of the miners and F. L. Davis for the owners.

[7]: [p175] On 2 November, the authorities in South Wales were enquiring about the procedure for requesting military aid in the event of disturbances caused by the striking miners.

[2] On 6 November, miners became aware of the owners' intention to deploy strikebreakers to keep pumps and ventilation going at the Glamorgan Colliery in Llwynypia.

[8]: [p111] Home Secretary Winston Churchill learned of that development and, after discussions with the War Office, delayed action on the request.

[8]: [p111] Despite that assurance, the local stipendiary magistrate sent a telegram to London later that day and requested military support, which the Home Office authorised.

[8]: [p114] A few shops remained untouched, notably that of the chemist Willie Llewellyn, which was rumoured to have been spared because he had been a famous Welsh international rugby footballer.

[8]: [p123] Although no authentic record exists of casualties since many miners would have refused treatment for fear of prosecution for their part in the riots, nearly 80 police and over 500 citizens were injured.

In the autobiographical "documentary novel" Cwmardy, the later communist trade union organiser Lewis Jones presents a stylistically romantic but closely-detailed, account of the riots and their agonising domestic and social consequences.

For example, in the chapter "Soldiers are sent to the Valley", he narrates an incident in which eleven strikers are killed by two volleys of rifle fire in the town square after which the miners adopt a grimly-retaliatory stance.

In that account, the end of the strike is hastened by organised terror directed at mine managers, leading to introduction of a minimum-wage act by the government that is hailed as a victory by the strikers.

[8]: [p111] The troops acted more circumspectly and were commanded with more common sense than the police, whose role under Lionel Lindsay was, in the words of historian David Smith, "more like an army of occupation".

Such was the strength of feeling, that almost forty years later, when speaking in Cardiff during the general election campaign of 1950, this time as Conservative Party leader, Churchill was forced to address the issue, stating: "When I was Home Secretary in 1910, I had a great horror and fear of having to become responsible for the military firing on a crowd of rioters and strikers.

In 1940, when Neville Chamberlain's war-time government was faltering, Clement Attlee secretly warned that the Labour Party might not follow Churchill because of his association with Tonypandy.

[14][15] In 2010, ninety-nine years after the riots, a Welsh local council made objections to an old military base being named after Churchill in the Vale of Glamorgan because of his sending troops into the Rhondda Valley.