Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

[1] Wittgenstein wrote the notes for the Tractatus while he was a soldier during World War I and completed it during a military leave in the summer of 1918.

In 1922 it was published together with an English translation and a Latin title, which was suggested by G. E. Moore as homage to Baruch Spinoza's Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (1670).

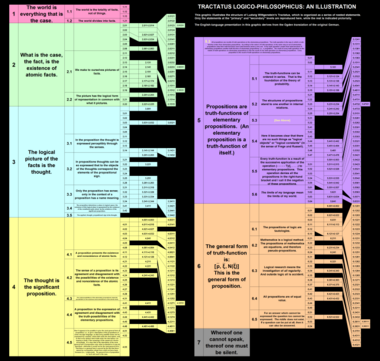

The Tractatus is written in an austere and succinct literary style, containing almost no arguments as such, but consists of 525 declarative statements altogether, which are hierarchically numbered.

Connecting his early and later writings on 'meaning as use' is his appeal to direct consequences of a term or phrase, reflected e.g. in his speaking of language as a 'calculus'.

The centrality and importance of these passages are corroborated and augmented by renewed examination of Wittgenstein's Nachlaß, as is done in "From Tractatus to Later Writings and Back – New Implications from the Nachlass" (de Queiroz 2023).

These are: The first chapter is very brief: This, along with the beginning of two, can be taken to be the relevant parts of Wittgenstein's metaphysical view that he will use to support his picture theory of language.

These sections concern Wittgenstein's view that the sensible, changing world we perceive does not consist of substance but of facts.

The notion of a static unchanging Form and its identity with Substance represents the metaphysical view that has come to be held as an assumption by the vast majority of the Western philosophical tradition since Plato and Aristotle, as it was something they agreed on.

It is commonly known now only in "Eastern" metaphysical views where the primary concept of substance is Qi, or something similar, which persists through and beyond any given Form.

It is predicated upon the idea that philosophy should be pursued in a way analogous to the natural sciences; that philosophers are looking to construct true theories.

[8][9] The philosophical significance of such a method for Wittgenstein was that it alleviated a confusion, namely the idea that logical inferences are justified by rules.

If an argument form is valid, the conjunction of the premises will be logically equivalent to the conclusion and this can be clearly seen in a truth table; it is displayed.

The final passages argue that logic and mathematics express only tautologies and are transcendental, i.e. they lie outside of the metaphysical subject's world.

Among the sensibly sayable for Wittgenstein are the propositions of natural science, and to the nonsensical, or unsayable, those subjects associated with philosophy traditionally – ethics and metaphysics, for instance.

[13] Although language differs from pictures in lacking direct pictorial mode of representation (e.g., it does not use colors and shapes to represent colors and shapes), still Wittgenstein believed that propositions are logical pictures of the world by virtue of sharing logical form with the reality which they represent (TLP 2.18–2.2).

And for similar reasons, no proposition is necessarily true except in the limiting case of tautologies, which Wittgenstein say lack sense (TLP 4.461).

[13] Instead, Wittgenstein believed objects to be the things in the world that would correlate to the smallest parts of a logically analyzed language, such as names like x.

[15]: p38 Anthony Kenny provides a useful analogy for understanding Wittgenstein's logical atomism: a slightly modified game of chess.

However, those features themselves are something Wittgenstein claimed we could not say anything about, because we cannot describe the relationship that pictures bear to what they depict, but only show it via fact-stating propositions (TLP 4.121).

[15]: p47 However, on the more recent "resolute" interpretation of the Tractatus (see below), the remarks on "showing" were not in fact an attempt by Wittgenstein to gesture at the existence of some ineffable features of language or reality, but rather, as Cora Diamond and James Conant have argued,[22] the distinction was meant to draw a sharp contrast between logic and descriptive discourse.

[23] Just as practical knowledge or skill (such as riding a bike) is not reducible to propositional knowledge according to Ryle, Wittgenstein also thought that the mastery of the logic of our language is a unique practical skill that does not involve any sort of propositional "knowing that", but rather is reflected in our ability to operate with senseful sentences and grasping their internal logical relations.

At the time of its publication in 1921, Wittgenstein concluded that the Tractatus had resolved all philosophical problems,[24] leaving one free to focus on what really matters – ethics, faith, music and so on.

Schlick eventually convinced Wittgenstein to meet with members of the circle to discuss the Tractatus when he returned to Vienna (he was then working as an architect).

[30] The main contention of such readings is that Wittgenstein in the Tractatus does not provide a theoretical account of language that relegates ethics and philosophy to a mystical realm of the unsayable.

[citation needed] Wittgenstein would not meet the Vienna Circle proper, but only a few of its members, including Moritz Schlick, Rudolf Carnap, and Friedrich Waismann.

Often, though, he refused to discuss philosophy, and would insist on giving the meetings over to reciting the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore with his chair turned to the wall.

[31] Alfred Korzybski credits Wittgenstein as an influence in his book, Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics.

[32] Casimir Lewy wrote that "I do not find...any evidence in Mind that the book had much direct influence on the development of philosophy in England during the period that I am reviewing [1976]", with the exception of Frank Ramsey's paper on universals.

The tracks were [T. 1] "The World is...", [T. 2] "In order to tell", [T. 4] "A thought is...", [T. 5] "A proposition is...", [T. 6] "The general form of a truth-function", and [T. 7] "Wovon man nicht sprechen kann".

[38] A manuscript of an early version of the Tractatus was discovered in Vienna in 1965 by Georg Henrik von Wright, who named it the Prototractatus and provided a historical introduction to a published facsimile with English translation: Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1971).