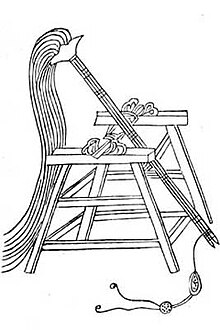

Mangonel

[1] Although the mangonel required more men to function, it was also less complex and faster to reload than the torsion-powered onager which it replaced in early Medieval Europe.

"[7] or mágganon "engine of war, axis of a pulley"[6][8][9] Mangonel was a general term for medieval stone-throwing artillery and was used more specifically to refer to manually (traction--) powered weapons.

They were used as defensive weapons stationed on walls and sometimes hurled hollowed out logs filled with burning charcoal to destroy enemy siege works.

[21][22] By the 1st century AD, commentators were interpreting other passages in texts such as the Zuo zhuan and Classic of Poetry as references to the mangonel: "the guai is 'a great arm of wood on which a stone is laid, and this by means of a device [ji] is shot off and so strikes down the enemy.

According to a stele in Barkul celebrating Tang Taizong's conquest of what is now Ejin Banner, the engineer Jiang Xingben made great advancements on mangonels that were unknown in ancient times.

[26][27] During the Jingde period (1004–1007), many young men rose in office due to their military accomplishments, and one such man, Zhang Cun, was said to have possessed no knowledge except how to operate a Whirlwind mangonel.

Regardless of the vector of transmission, it appeared in the eastern Mediterranean by the late 6th century AD, where it replaced torsion powered siege engines such as the ballista and onager.

It was probably also safer than the twisted cords of torsion weapons, "whose bundles of taut sinews stored up huge amounts of energy even in resting state and were prone to catastrophic failure when in use.

"[37][2][38][4] At the same time, the late Roman Empire seems to have fielded "considerably less artillery than its forebears, organised now in separate units, so the weaponry that came into the hands of successor states might have been limited in quantity.

The account contained describes a captured Byzantine soldier named Busas who taught the Avars how to construct a "besieging machine" which led to their conquest of Appiaria in 587.

David Graff and Purton argue that the account by Theophylact has chronological problems and does not explain why the machine used by the Avars in the Miracles was treated as a novelty in either 586 or 597, since the Byzantines would have known about it in both cases.

[49] In the 890s, Abbo Cernuus described mango or manganaa used at the Siege of Paris (885–886) which had high posts, presumably meaning they used trebuchet-type throwing arms.

[2] The catapult, the account of which has been translated from the Greek several times, was quadrangular, with a wide base but narrowing towards the top, using large iron rollers to which were fixed timber beams "similar to the beams of big houses", having at the back a sling, and at the front thick cables, enabling the arm to be raised and lowered, and which threw "enormous blocks into the air with a terrifying noise".

[55] Thus, on the basis of fairly hard evidence of unknown machinery in Joshua the Stylite and Agathias, as well as good indications of its construction in Procopius (especially when read against Strategikon), it is likely that the traction trebuchet had become known in the eastern Mediterranean area at the latest by around 500.

Most accounts of mangonels describe them as light artillery weapons while actual penetration of defenses was the result of mining or siege towers.

[57] At the Siege of Kamacha in 766, Byzantine defenders used wooden cover to protect themselves from the enemy artillery while inflicting casualties with their stone throwers.

"[58] During the siege of Baghdad in 865, defensive artillery was responsible for repelling an attack on the city gate while mangonels on boats claimed a hundred of the defenders' lives.

[61] West of China, the mangonel remained the primary siege engine until the late 12th century when it was replaced by the counterweight trebuchet.

[62] In China the mangonel was the primary siege engine until the counterweight trebuchet was introduced during the Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty in the 13th century.

Despite its greater range, counterweight trebuchets had to be constructed close to the site of the siege unlike mangonels, which were smaller, lighter, cheaper, and easier to take apart and put back together again where necessary.