Train horn

This is exacerbated by the train's enormous weight and inertia, which make it difficult to quickly stop when encountering an obstacle.

Also, trains generally do not stop at level crossings, instead relying on pedestrians and vehicles to clear the tracks when they pass.

Due to the encroachment of development, some suburban dwellers have opposed railroad use of the air horn as a trackside warning device.

[1] Residents in some communities have attempted to establish quiet zones, in which train crews are instructed not to sound their horns, except in case of emergency.

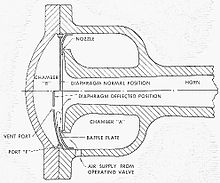

It passes through a narrow opening between a nozzle and a circular diaphragm in the power chamber, then out through the flaring horn bell.

Once this occurs, the diaphragm is deflected back and is no longer sealed against the nozzle, causing the power chamber to lose its airtightness.

The diaphragm's constant back-and-forth oscillation creates sound waves, which are amplified by the large flared horn bell.

The bell's length determines the waves' wavelength, and thus the fundamental frequency (pitch) of the note produced by the horn (measured in hertz).

North American diesel locomotives manufactured prior to the 1990s used an air valve actuated by the engineer through the manipulation of a lever or pull cord.

Current production locomotives from GE Transportation Systems and Electro-Motive Diesel use a lever-actuated solenoid valve.

Air horns are no exception, and railroad mechanical forces mount these on locomotives where they are deemed most effective at projecting sound, and for ease of maintenance.

Locomotive engineers retain the authority to vary this pattern as necessary for crossings in close proximity, and are allowed to sound the horn in emergency situations no matter where the location.

[citation needed] The following are the required horn signals listed in the operating rules of most North American railroads, along with their meanings.

The "loud" mode is intended for emergency situations, such as when a person or vehicle is on the tracks in front of an incoming train.

[12] Train horns must produce a minimum sound level of 96 decibels (dB) in a 30-metre (100 ft) radius from the locomotive.

[19] However, because of noise complaints, new rules were introduced in 2007:[20] British train horns have two tones, high or low, and in some cases, a loud or soft setting.

Co. of Kansas City, Missouri offered airhorns for use on railroad equipment prior to the Second World War.

Leslie Controls, Inc., originally the Leslie Company of Lyndhurst, New Jersey, later Parsippany, finally relocating to Tampa, Florida in 1985, began horn production by obtaining the rights to manufacture the Kockums Mekaniska Verkstad product line of "Tyfon" brand airhorns, marketing these for railroad use beginning in the 1930s.

Their model A200 series would later grace the rooftops of countless locomotives, such as the legendary Pennsylvania Railroad GG1, as well as thousands of EMD E and F-units.

Leslie eventually introduced their own line of multi-note airhorns, known as the "Chime-Tone" series, in direct competition with AirChime.

Developed by Kockums, this horn utilized a back-pressure power chamber design in order to enhance diaphragm oscillation.

[31] Prime Manufacturing, Inc. had produced locomotive appliances for many years prior to their entry into the air horn market in 1972.

Sales were brisk (railroads such as Union Pacific and the Burlington Northern were notable customers) but ultimately disappointing.

Finding themselves increasingly unable to compete in a niche market dominated by Leslie Controls and AirChime, Prime ceased air horn production c. 1999.

Overshadowed later on by Leslie and AirChime, WABCO eventually ceased production of most horns for the North American market.