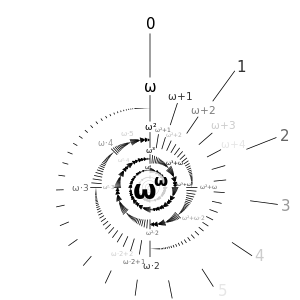

Transfinite induction

Given a class function[3] G: V → V (where V is the class of all sets), there exists a unique transfinite sequence F: Ord → V (where Ord is the class of all ordinals) such that As in the case of induction, we may treat different types of ordinals separately: another formulation of transfinite recursion is the following: Transfinite Recursion Theorem (version 2).

Given a set g1, and class functions G2, G3, there exists a unique function F: Ord → V such that Note that we require the domains of G2, G3 to be broad enough to make the above properties meaningful.

The uniqueness of the sequence satisfying these properties can be proved using transfinite induction.

More generally, one can define objects by transfinite recursion on any well-founded relation R. (R need not even be a set; it can be a proper class, provided it is a set-like relation; i.e. for any x, the collection of all y such that yRx is a set.)

However, if the relation in question is already well-ordered, one can often use transfinite induction without invoking the axiom of choice.

[4] For example, many results about Borel sets are proved by transfinite induction on the ordinal rank of the set; these ranks are already well-ordered, so the axiom of choice is not needed to well-order them.

The following construction of the Vitali set shows one way that the axiom of choice can be used in a proof by transfinite induction: The above argument uses the axiom of choice in an essential way at the very beginning, in order to well-order the reals.

If it is not possible to define a unique example of such a set at each stage, then it may be necessary to invoke (some form of) the axiom of choice to select one such at each step.

For inductions and recursions of countable length, the weaker axiom of dependent choice is sufficient.