Transposable element

The vast number of variables in the transposon makes data analytics difficult but combined with other sequencing technologies significant advances may be made in the understanding and treatment of disease.

[4] Transposable elements make up about half of the genome in a eukaryotic cell, accounting for much of human genetic diversity.

[6] Barbara McClintock discovered the first TEs in maize (Zea mays) at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York.

[7] In the winter of 1944–1945, McClintock planted corn kernels that were self-pollinated, meaning that the silk (style) of the flower received pollen from its own anther.

[7] These kernels came from a long line of plants that had been self-pollinated, causing broken arms on the end of their ninth chromosomes.

McClintock found that genes could not only move but they could also be turned on or off due to certain environmental conditions or during different stages of cell development.

[9] She presented her report on her findings in 1951, and published an article on her discoveries in Genetics in November 1953 entitled "Induction of Instability at Selected Loci in Maize".

[12] She was awarded a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1983 for her discovery of TEs, more than thirty years after her initial research.

Some researchers also identify a third class of transposable elements,[19] which has been described as "a grab-bag consisting of transposons that don't clearly fit into the other two categories".

[26] New discoveries of transposable elements have shown the exact distribution of TEs with respect to their transcription start sites (TSSs) and enhancers.

Diseases often caused by TEs include One study estimated the rate of transposition of a particular retrotransposon, the Ty1 element in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Certain mutated plants have been found to have defects in methylation-related enzymes (methyl transferase) which cause the transcription of TEs, thus affecting the phenotype.

Bacteria may undergo high rates of gene deletion as part of a mechanism to remove TEs and viruses from their genomes, while eukaryotic organisms typically use RNA interference to inhibit TE activity.

In vertebrate animal cells, nearly all 100,000+ DNA transposons per genome have genes that encode inactive transposase polypeptides.

Although both types are inactive, one copy of Hsmar1 found in the SETMAR gene is under selection as it provides DNA-binding for the histone-modifying protein.

[61] The frequency and location of TE integrations influence genomic structure and evolution and affect gene and protein regulatory networks during development and in differentiated cell types.

TEs also serve to generate repeating sequences that can form dsRNA to act as a substrate for the action of ADAR in RNA editing.

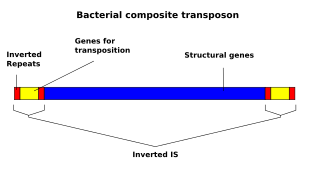

[63] TEs can contain many types of genes, including those conferring antibiotic resistance and the ability to transpose to conjugative plasmids.

Transposons do not always excise their elements precisely, sometimes removing the adjacent base pairs; this phenomenon is called exon shuffling.

[66] There is a hypothesis that states that TEs might provide a ready source of DNA that could be co-opted by the cell to help regulate gene expression.

Research showed that many diverse modes of TEs co-evolution along with some transcription factors targeting TE-associated genomic elements and chromatin are evolving from TE sequences.

[27] Transposable elements can be harnessed in laboratory and research settings to study genomes of organisms and even engineer genetic sequences.

Many computer programs exist to perform de novo repeat identification, all operating under the same general principles.

[68] As short tandem repeats are generally 1–6 base pairs in length and are often consecutive, their identification is relatively simple.

[67] Dispersed repetitive elements, on the other hand, are more challenging to identify, due to the fact that they are longer and have often acquired mutations.

Although most of the TEs were located on introns, the experiment showed a significant difference in gene expressions between the population in Africa and other parts of the world.

Downregulation of such genes has caused Drosophila to exhibit extended developmental time and reduced egg to adult viability.

[72] This is not hard to believe, since it is logical for a population to favor higher egg to adult viability, therefore trying to purge the trait caused by this specific TE adaptation.

In the research done with silkworms, "An Adaptive Transposable Element insertion in the Regulatory Region of the EO Gene in the Domesticated Silkworm", a TE insertion was observed in the cis-regulatory region of the EO gene, which regulates molting hormone 20E, and enhanced expression was recorded.

[74] These three experiments all demonstrated different ways in which TE insertions can be advantageous or disadvantageous, through means of regulating the expression level of adjacent genes.

B . Mechanism of transposition: Two transposases recognize and bind to TIR sequences, join and promote DNA double-strand cleavage. The DNA-transposase complex then inserts its DNA cargo at specific DNA motifs elsewhere in the genome, creating short TSDs upon integration. [ 16 ]