Treaty of Waitangi claims and settlements

Successive governments have increasingly provided formal legal and political opportunity for Māori to seek redress for what are seen as breaches by the Crown of guarantees set out in the Treaty of Waitangi.

While it has resulted in putting to rest a number of significant longstanding grievances, the process has been subject to criticisms including those who believe that the redress is insufficient to compensate for Māori losses.

Much of this has been generated by iwi (Māori tribal groups), a lasting example is the Ngāti Awa Research Centre established in 1989.

[15][16] In 1985 the Fourth Labour Government extended the Tribunal's powers to allow it to consider Crown actions dating back to 1840,[17] including the period covered by the New Zealand Wars.

[19] Featured in the Waikato-Tainui Ngāi Tahu settlements in 2009 and all subsequent settlements was redress described in these three areas: a historical account of grievances and an apology, a financial package of cash and transfer of assets (no compulsory acquisition of private land), and cultural redress, where a range of Māori interests are acknowledged which often related to sites of interest and Māori association with the environment.

The Office of Treaty Settlements was established in the Ministry of Justice to develop government policy on historical claims.

The Crown held a series of consultation hui around the country, at which Māori vehemently rejected the proposals including such a limitation in advance of the extent of claims being fully known.

The Minister of Justice and Treaty Negotiations at the time, Sir Douglas Graham, is credited with leading a largely conservative National government to make these breakthroughs.

[20] Government Minister Chris Finlayson was part of this and states the purpose was to create an 'institutional safeguard' to protect settlements and support them being durable and final.

Over time, however, New Zealand law began to regulate commercial fisheries, so that Māori control was substantially eroded.

This included 50% of Sealord Fisheries and 20% of all new species brought under the quota system, more shares in fishing companies, and $18 million in cash.

Waikato-Tainui's confiscation claims were settled for a package worth $170 million, in a mixture of cash and Crown-owned land.

Ngāi Tahu's claims covered a large proportion of the South Island of New Zealand, and related to the Crown's failure to meet its end of the bargain in land sales that took place from the 1840s.

[28] Chris Finlayson was one of the lawyers working for Ngāi Tahu during the mid 1990s as the negotiations were taking place, he states a litigious approach was used and was needed to keep things moving.

[29] Ngāi Tahu sought recognition of their relationship with the land, as well as cash and property, and a number of novel arrangements were developed to address this.

In addition, but not counted by the government as part of the redress package, the tribes will receive rentals that have accumulated on the land since 1989, valued at NZ$223 million.

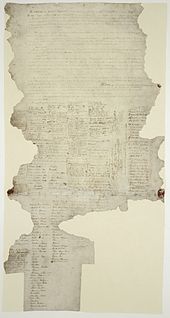

The first stage of the report was released in November 2014, and found that Māori chiefs in Northland never agreed to give up their sovereignty when they signed the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840.

[79] A month before the report's official release a letter was sent to Te Ururoa Flavell, Minister for Māori Development, to notify him of the Tribunal's conclusion.

Tribunal manager Julie Tangaere said at the report's release to the Ngapuhi claimants:Your tupuna [ancestors] did not give away their mana at Waitangi, at Waimate, at Mangungu.

[81] In relation to the former, a summary report (entitled "Ngāpuhi Speaks") of evidence presented to the Waitangi Tribunal concluded that: Ngāti Tūwharetoa academic Hemopereki Simon outlined a case in 2017, using Ngati Tuwharetoa as a case study, for how hapū and iwi that did not sign the Treaty still maintain mana motuhake and how the sovereignty of the Crown could be considered questionable.

The “fiscal envelope” decision by the Government in 1994 had a consultation period in which most Māori 'overwhelmingly rejected' the policy and sparked protests throughout New Zealand.

[92][93] The Orewa Speech in 2004 saw the National Party for the first time take up the term "Treaty of Waitangi Grievance Industry".

National's Māori Affairs spokeswoman Georgina te Heuheu, who was Associate Minister to Sir Douglas Graham, was replaced in the role by Gerry Brownlee.

[99]Research conducted by academics Professor Margaret Mutu and Dr Tiopira McDowell of the University of Auckland found that the purpose of the settlements was to extinguish claims so that claimants cannot have State Owned Enterprise and Crown Forest lands returned to them through binding recommendations.