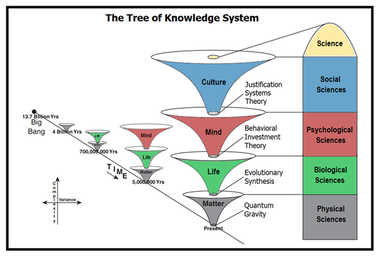

Tree of knowledge system

The Tree of Knowledge (ToK) System was developed by Gregg Henriques, who is a professor and core faculty member in the Combined-Integrated Doctoral Program in Clinical and School Psychology at James Madison University.

[1] The ToK System is part of a larger Unified Theory of Knowledge that Henriques describes as a consilient scientific humanistic philosophy for the 21st Century.

The theory is that, following Matter, Life, Mind and Culture each represent complex adaptive landscapes that are organized and mediated by novel emergent information processing and communication systems.

Specifically, DNA/RNA store information that is processed by cells which then engage in intercellular communication to create the plane of existence called Life.

Similarly, the brain and nervous system store and process information in animals which then engage in communication networks on the complex adaptive plane called Mind.

Specifically, the domains of the physical, biological, (basic) psychological and social sciences map the ontic dimensions of matter, life, mind and culture.

[3] Henriques argues that comparative psychology, ethology, and (animal) cognitive behavioral neuroscience should all be thought of as parts of the discipline that maps the animal-mental domain.

Culture in the ToK system refers to the set of sociolinguistic behaviors, which range from large scale nation states to individual human justifications for particular actions.

Some of the difficulties combining these two pillars of physical science are philosophical in nature and it is possible that the macro view of knowledge offered by the ToK may eventually aid in the construction of a coherent theory of quantum gravity.

The modern synthesis refers to the merger of genetics with natural selection which occurred in the 1930s and 1940s and offers a reasonably complete framework for understanding the emergence of biological complexity.

Although there remain significant gaps in biological knowledge surrounding questions such as the origin of life and the emergence of sexual reproduction, the modern synthesis represents the most complete and well-substantiated joint point.

A basic initial claim of JUST is that the process of justification is a crucial component of human mental behavior at both the individual and societal level.

Arguments, debates, moral dictates, rationalizations, and excuses all involve the process of explaining why one's claims, thoughts or actions are warranted.

In virtually every form of social exchange, from warfare to politics to family struggles to science, humans are constantly justifying their behavioral investments to themselves and others.

[8][9] Specifically, Henriques argues that the field lacks a clear definition, an agreed upon subject matter, and a coherent conceptual framework.

This conclusion is bolstered by the fact that as psychology has lumbered along acquiring findings but not foundational clarity, the fragmentation of human knowledge has grown exponentially.

As such, the different schools of thought in psychology are like the blind men who each grab a part of the elephant and proclaim they have discovered its true nature.

In his 2003 Review of General Psychology paper,[8] Henriques used the ToK System with the attempt to clarify and align the views of B.F. Skinner and Sigmund Freud.

These luminaries were chosen because when one considers their influence and historical opposition, it can readily be argued that they represent two schools of thought that are the most difficult to integrate.

The reason is given by the detail with which alternatives have been worked out, be they historical studies of institutional development or critical commentaries on the rhetorical structure of psychology's literature.

In other words, the discipline has historically spanned two fundamentally separate problems: If, as previously thought, nature simply consisted of levels of complexity, psychology would not be crisply defined in relationship to biology or the social sciences.

As with Henriques' proposed conception of human psychology, both of these disciplines adopt an object level perspective (molecular and cellular, respectively) on phenomena that simultaneously exist as part of meta-level system processes (life and mind, respectively).

[9] Though David A. F. Haaga "congratulate[d] Dr. Henriques' ambitious, scholarly, provocative paper", and "found the Tree of Knowledge taxonomy, the theoretical joint points, the evolutionary history, and the levels of emergent properties highly illuminating", he asks the rhetorical questions, If it is so difficult to define terms such as 'psychology' with such precision, why bother?

Lilienfeld suggested that the solution to the scientist-practitioner gulf isn't definitional, but in "train[ing] future clinical scientists to appreciate the proper places of romanticism and empiricism within science".

Sentience is conceptualized as a "level 3" phenomenon, possessed by many animals other than humans and is defined as a "perceived" electro-neuro-chemical representation of animal-environment relations.

The ingredient of neurological behavior that allows for the emergence of mental experience is considered the "hard" problem of consciousness and the ToK System does not address this question explicitly.

It was a stressful day, traffic was bad, and you know that if work needs to be done, I can’t just leave it.” The words represent the sociolinguistic dimension and are understood as a function of justification.

Henriques also believes that history seems to attest that the absence of a collective worldview ostensibly condemns humanity to an endless series of conflicts that inevitably stem from incompatible, partially correct, locally situated justification systems.

Thus, from Henriques' perspective, there are good reasons for believing that if there was a shared, general background of explanation, humanity might be able to achieve much greater levels of harmonious relations.