Tributary system of China

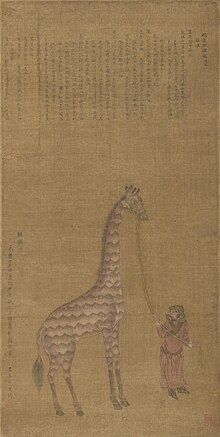

The other states had to send a tributary envoy to China on schedule, who would kowtow to the Chinese emperor as a form of tribute, and acknowledge his superiority and precedence.

The other countries followed China's formal ritual in order to keep the peace with the more powerful neighbor and be eligible for diplomatic or military help under certain conditions.

They suggest a Sinocentric system, in which Chinese culture was central to the self-identification of many elite groups in the surrounding Asian countries.

[3] By the late 19th century, China had become part of a European-style community of sovereign states and established diplomatic relations with other countries in the world following international law.

John King Fairbank and Teng Ssu-yu created the "tribute system" theory in a series of articles in the early 1940s to describe "a set of ideas and practices developed and perpetuated by the rulers of China over many centuries.

"[6] The concept was developed and became influential after 1968, when Fairbank edited and published a conference volume, The Chinese World Order, with fourteen essays on China's pre-modern relations with Vietnam, Korea, Inner Asia and Tibet, Southeast Asia and the Ryukyus, as well as an Introduction and essays describing Chinese views of the world order.

On the opposite side of the tributary relationship spectrum was Japan, whose leaders could hurt their own legitimacy by identifying with Chinese authority.

Since geographical density and proximity was not an issue, regions with multiple kings such as the Sultanate of Sulu benefited immensely from this exchange.

[21] Participation in a tributary relationship with a Chinese dynasty could also be predicated on cultural or civilizational motivations rather than material and monetary benefits.

[22] Meanwhile, Japan avoided direct contact with Qing China and instead manipulated embassies from neighboring Joseon and Ryukyu to make it falsely appear as though they came to pay tribute.

[26] The Ming founder Hongwu Emperor adopted a maritime prohibition policy and issued tallies to "tribute-bearing" embassies for missions.

Although a move out of necessity, we may still say that they have been able to correct their mistake[31]Goryeo's rulers called themselves "Great King" viewing themselves as the sovereigns of the Goryeo-centered world of Northeast Asia.

[32] As the struggle between the Northern Yuan and the Red Turban Rebellion and the Ming remained indecisive, Goryeo retained neutrality despite both sides pleading for their assistance in order to break this stalemate.

The nature of these bilateral contacts evolved gradually from political and ceremonial acknowledgment to cultural exchanges; and the process accompanied the growing commercial ties which developed over time.

This relationship continued until 1549 (except the 1411-1432 period) when Japan chose to end its recognition of China's regional hegemony and cancel any further tribute missions.

[40] Wei Yuan, the 19th century Chinese scholar, considered Thailand to be the strongest and most loyal of China's Southeast Asian tributaries, citing the time when Thailand offered to directly attack Japan to divert the Japanese in their planned invasions of Korea and the Asian mainland, as well as other acts of loyalty to the Ming dynasty.

[41] Thailand was welcoming and open to Chinese immigrants, who dominated commerce and trade, and achieved high positions in the government.

[44] The Hongwu Emperor was firmly opposed to military expeditions in Southeast Asia and only rebuked Vietnam's conquest of Champa, which had sent tribute missions to China seeking help.

Due to their participation in the tributary system, Vietnamese rulers behaved as though China was not a threat and paid very little military attention to it.

Rather, Vietnamese leaders were clearly more concerned with quelling chronic domestic instability and managing relations with kingdoms to their south and west.