Spore

In biology, a spore is a unit of sexual (in fungi) or asexual reproduction that may be adapted for dispersal and for survival, often for extended periods of time, in unfavourable conditions.

The main difference between spores and seeds as dispersal units is that spores are unicellular, the first cell of a gametophyte, while seeds contain within them a developing embryo (the multicellular sporophyte of the next generation), produced by the fusion of the male gamete of the pollen tube with the female gamete formed by the megagametophyte within the ovule.

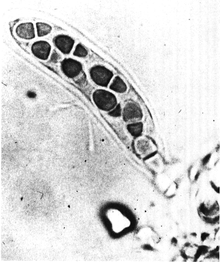

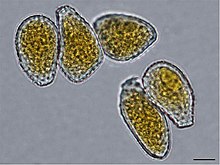

Below is a table listing the mode of classification, name, identifying characteristic, examples, and images of different spore species.

Some markings represent apertures, places where the tough outer coat of the spore can be penetrated when germination occurs.

[9] Envelope-enclosed spore tetrads are taken as the earliest evidence of plant life on land,[10] dating from the mid-Ordovician (early Llanvirn, ~470 million years ago), a period from which no macrofossils have yet been recovered.

[11] Individual trilete spores resembling those of modern cryptogamic plants first appeared in the fossil record at the end of the Ordovician period.

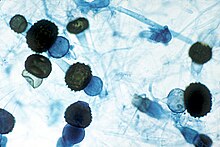

[12] In fungi, both asexual and sexual spores or sporangiospores of many fungal species are actively dispersed by forcible ejection from their reproductive structures.

Attracting insects, such as flies, to fruiting structures, by virtue of their having lively colours and a putrid odour, for dispersal of fungal spores is yet another strategy, most prominently used by the stinkhorns.

In Common Smoothcap moss (Atrichum undulatum), the vibration of sporophyte has been shown to be an important mechanism for spore release.

[15] In the case of spore-shedding vascular plants such as ferns, wind distribution of very light spores provides great capacity for dispersal.

[18] The spores found in microfossils, also known as cryptospores, are well preserved due to the fixed material they are in as well as how abundant and widespread they were during their respective time periods.

[3] Both cryptospores and modern spores have diverse morphology that indicate possible environmental conditions of earlier periods of Earth and evolutionary relationships of plant species.