Tristan Tzara

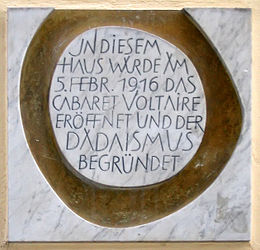

[33] Hugo Ball recorded this period, noting that Tzara and Marcel Janco, like Hans Arp, Arthur Segal, Otto van Rees, and Max Oppenheimer "readily agreed to take part in the cabaret".

"[39] Other opinions link Dada's beginnings with much earlier events, including the experiments of Alfred Jarry, André Gide, Christian Morgenstern, Jean-Pierre Brisset, Guillaume Apollinaire, Jacques Vaché, Marcel Duchamp, and Francis Picabia.

[40] In the first of the movement's manifestos, Ball wrote: "[The booklet] is intended to present to the Public the activities and interests of the Cabaret Voltaire, which has as its sole purpose to draw attention, across the barriers of war and nationalism, to the few independent spirits who live for other ideals.

According to Hans Richter, it included, alongside Tzara, figures ranging from Ernst, Arp, Baader, Breton and Aragon to Kruscek, Evola, Rafael Lasso de la Vega, Igor Stravinsky, Vicente Huidobro, Francesco Meriano and Théodore Fraenkel.

[65] In one instance, as part of a series of events in which Dadaists mocked established authors, Tzara and Arp falsely publicized that they were going to fight a duel in Rehalp, near Zürich, and that they were going to have the popular novelist Jakob Christoph Heer for their witness.

[94] Eugen Lovinescu, editor of Sburătorul and one of Vinea's rivals on the modernist scene, acknowledged the influence exercised by Tzara on the younger avant-garde authors, but analyzed his work only briefly, using as an example one of his pre-Dada poems, and depicting him as an advocate of literary "extremism".

[108] Basing his statement on a note supposedly authored by Huelsenbeck, Breton also accused Tzara of opportunism, claiming that he had planned wartime editions of Dada works in such a manner as not to upset actors on the political stage, making sure that German Dadaists were not made available to the public in countries subject to the Supreme War Council.

Alongside Cocteau, Arp, Ribemont-Dessaignes, and Éluard, the pro-Tzara faction included Erik Satie, Theo van Doesburg, Serge Charchoune, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Marcel Duchamp, Ossip Zadkine, Jean Metzinger, Ilia Zdanevich, and Man Ray.

[124] In a 1927 interview with the publication, he voiced his opposition to the Surrealist group's adoption of communism, indicating that such politics could only result in a "new bourgeoisie" being created, and explaining that he had opted for a personal "permanent revolution", which would preserve "the holiness of the ego".

[68] This period saw the publication of The Approximate Man (1931), alongside the volumes L'Arbre des voyageurs ("The Travelers' Tree", 1930), Où boivent les loups ("Where Wolves Drink", 1932), L'Antitête ("The Antihead", 1933) and Grains et issues ("Seed and Bran", 1935).

In 1936, Richter recalled, he published a series of photographs secretly taken by Kurt Schwitters in Hanover, works which documented the destruction of Nazi propaganda by the locals, ration stamp with reduced quantities of food, and other hidden aspects of Hitler's rule.

As early as 1934, Tzara, together with Breton, Éluard and communist writer René Crevel, organized an informal trial of independent-minded Surrealist Salvador Dalí, who was at the time a confessed admirer of Hitler, and whose portrait of William Tell had alarmed them because it shared likeness with Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin.

[143] Historian Irina Livezeanu notes that Tzara, who agreed with Stalinism and shunned Trotskyism, submitted to the PCF cultural demands during the writers' congress of 1935, even when his friend Crevel committed suicide to protest the adoption of socialist realism.

[154] In 1949, he introduced Picasso to art dealer Heinz Berggruen (thus helping start their lifelong partnership),[164] and, in 1951, wrote the catalog for an exhibit of works by his friend Max Ernst; the text celebrated the artist's "free use of stimuli" and "his discovery of a new kind of humor.

[146][154] This followed an invitation on the part of Hungarian writer Gyula Illyés, who wanted his colleague to be present at ceremonies marking the rehabilitation of László Rajk (a local communist leader whose prosecution had been ordered by Joseph Stalin).

[174] Like in the cases of Eugène Ionesco and Fondane, Cernat proposes, Samyro sought self-exile to Western Europe as a "modern, voluntarist" means of breaking with "the peripheral condition",[175] which may also serve to explain the pun he selected for a pseudonym.

[182] Nine years after Emilian's polemic text, fascist poet and journalist Radu Gyr published an article in Convorbiri Literare, in which he attacked Tzara as a representative of the "Judaic spirit", of the "foreign plague" and of "materialist-historical dialectics".

"[193] Cernat notes: "That which essentially unifies, during [the 1910s], the poetic output of Adrian Maniu, Ion Vinea and Tristan Tzara is an acute awareness of literary conventions, a satiety [...] in respect to calophile literature, which they perceived as exhausted.

să ne coborâm în râpa, care-i Dumnezeu când cască[201] let's descend into the precipice that is God yawning In his Înserează (roughly, "Night Falling"), probably authored in Mangalia, Tzara writes:

seara bate semne pe far peste goarnele vagi de apă când se întorc pescarii cu stele pe mâini și trec vapoarele și planetele[199] the evening stamps signs on the lighthouse over the vague bugles of water when fishermen return with stars on their arms and ships and planets pass by Cernat notes that Nocturnă ("Nocturne") and Înserează were the pieces originally performed at Cabaret Voltaire, identified by Hugo Ball as "Rumanian poetry", and that they were recited in Tzara's own spontaneous French translation.

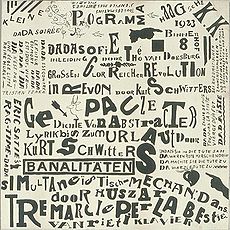

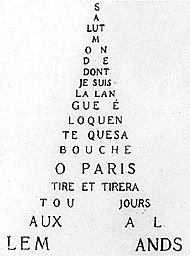

[110][217][218] The Romanian writer also spent the Dada period issuing a long series of manifestos, which were often authored as prose poetry,[85] and, according to Cardinal, were characterized by "rumbustious tomfoolery and astringent wit", which reflected "the language of a sophisticated savage".

[85] Tzara was aware that the public could find it difficult to follow his intentions, and, in a piece titled Le géant blanc lépreux du paysage ("The White Leprous Giant in the Landscape") even alluded to the "skinny, idiotic, dirty" reader who "does not understand my poetry.

Largely through exchanges between commentators who act as third parties, the text presents the tribulations of a love triangle (a poet, a bored woman, and her banker husband, whose character traits borrow the clichés of conventional drama), and in part reproduces settings and lines from Hamlet.

[85][237] Cardinal calls the piece "an extended meditation on mental and elemental impulses [...] with images of stunning beauty",[68] while Breitchman, who notes Tzara's rebellion against the "excess baggage of [man's] past and the notions [...] with which he has hitherto tried to control his life", remarks his portrayal of poets as voices who can prevent human beings from destroying themselves with their own intellects.

The world imagined by Tzara abandons symbols of the past, from literature to public transportation and currency, while, like psychologists Sigmund Freud and Wilhelm Reich, the poet depicts violence as a natural means of human expression.

This was the case in his homeland during 1928, when the first avant-garde manifesto issued by unu magazine, written by Sașa Pană and Moldov, cited as its mentors Tzara, writers Breton, Ribemont-Dessaignes, Vinea, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, and Tudor Arghezi, as well as artists Constantin Brâncuși and Theo van Doesburg.

[244] One of the Romanian writers to claim inspiration from Tzara was Jacques G. Costin, who nevertheless offered an equally good reception to both Dadaism and Futurism,[245] while Ilarie Voronca's Zodiac cycle, first published in France, is traditionally seen as indebted to The Approximate Man.

Max Ernst depicts him as the only mobile character in the Dadaists' group portrait Au Rendez-vous des Amis ("A Friends' Reunion", 1922),[142] while, in one of Man Ray's photographs, he is shown kneeling to kiss the hand of an androgynous Nancy Cunard.

In his personal diary, published long after he and Tzara had died, Pandrea depicted the poet as an opportunist, accusing him of adapting his style to political requirements, of dodging military service during World War I, and of being a "Lumpenproletarian".

[290] Pandrea's text, completed just after Tzara's visit to Romania, claimed that his founding role within the avant-garde was an "illusion [...] which has swelled up like a multicolored balloon", and denounced him as "the Balkan provider of interlope odalisques, [together] with narcotics and a sort of scandalous literature.