The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman

Many of his similes, for instance, are reminiscent of the works of the metaphysical poets of the 17th century,[1] and the novel as a whole, with its focus on the problems of language, has constant regard for John Locke's theories in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

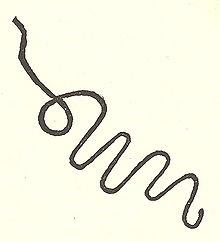

But it is one of the central jokes of the novel that he cannot explain anything simply, that he must make explanatory diversions to add context and colour to his tale, to the extent that Tristram's own birth is not even reached until Volume III.

Consequently, apart from Tristram as narrator, the most familiar and important characters in the book are his father Walter, his mother, his Uncle Toby, Toby's servant Trim, and a supporting cast of popular minor characters, including the chambermaid Susannah, Doctor Slop and the parson Yorick, who later became Sterne's favourite nom de plume and a very successful publicity stunt.

Most of the action is concerned with domestic upsets or misunderstandings, which find humour in the opposing temperaments of Walter—splenetic, rational, and somewhat sarcastic—and Uncle Toby, who is gentle, uncomplicated, and a lover of his fellow man.

In between such events, Tristram as narrator finds himself discoursing at length on sexual practices, insults, the influence of one's name and noses, as well as explorations of obstetrics, siege warfare and philosophy, as he struggles to marshal his material and finish the story of his life.

The first to note them was physician, poet and Portico Library Chair John Ferriar, who did not see them negatively and commented:[5][6] If [the reader's] opinion of Sterne's learning and originality be lessened by the perusal, he must, at least, admire the dexterity and the good taste with which he has incorporated in his work so many passages, written with very different views by their respective authors.Ferriar believed that Sterne was ridiculing Burton's The Anatomy of Melancholy, mocking its solemn tone and endeavours to prove indisputable facts by weighty quotations.

Tristram Shandy gives a ludicrous turn to solemn passages from respected authors that it incorporates, as well as to the consolatio literary genre.

[5][7] Among the subjects of such ridicule were some of the opinions contained in Robert Burton's The Anatomy of Melancholy, a book that mentions sermons as the most respectable type of writing, and one that was favoured by the learned.

His book consists mostly of a collection of the opinions of a multitude of writers (he modestly refrains from adding his own) divided into quaint and old-fashioned categories.

Burton indulges himself in a Utopian sketch of a perfect government in his introductory address to the reader, and this forms the basis of the notions of Tristram Shandy on the subject.

Other major influences are Cervantes and Montaigne's Essays, as well as the significant inter-textual debt to The Anatomy of Melancholy,[5] Swift's Battle of the Books, and the Scriblerian collaborative work The Memoirs of Martinus Scriblerus.

Sterne is by turns respectful and satirical of Locke's theories, using the association of ideas to construct characters' "hobby-horses", or whimsical obsessions, that both order and disorder their lives in different ways.

[2] There is a significant body of critical opinion that argues that Tristram Shandy is better understood as an example of an obsolescent literary tradition of "Learned Wit", partly following the contribution of D. W.

Arthur Schopenhauer called Tristram Shandy one of "the four immortal romances"[3] and Ludwig Wittgenstein considered it "one of my favourite books".

[20] The young Karl Marx was a devotee of Tristram Shandy, and wrote a still-unpublished short humorous novel, Scorpion and Felix, that was obviously influenced by Sterne's work.

[21][23] Writing in The Times in January 2021, critic Michael Henderson disparaged the novel, stating that it "honks like John Coltrane, and is not nearly so funny."

Tristram Shandy has also been seen by formalists and other literary critics as a forerunner of many narrative devices and styles used by modernist and postmodernist authors such as James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Carlos Fuentes, Milan Kundera and Salman Rushdie.

[29] In 1766, at the height of the debate about slavery in Britain, Ignatius Sancho wrote a letter to Sterne[30] encouraging the writer to use his pen to lobby for the abolition of the slave trade.

[32]In 2005, BBC Radio 4 broadcast an adaptation by Graham White in ten 15-minute episodes directed by Mary Peate, with Neil Dudgeon as Tristram, Julia Ford as Mother, David Troughton as Father, Adrian Scarborough as Toby, Paul Ritter as Trim, Tony Rohr as Dr Slop, Stephen Hogan as Obadiah, Helen Longworth as Susannah, Ndidi Del Fatti as Great-Grandmother, Stuart McLoughlin as Great-Grandfather/Pontificating Man and Hugh Dickson as Bishop Hall.

The book was adapted on film in 2006 as A Cock and Bull Story, directed by Michael Winterbottom, written by Frank Cottrell Boyce (credited as Martin Hardy, in a complicated metafictional twist), and starring Steve Coogan, Rob Brydon, Keeley Hawes, Kelly Macdonald, Naomie Harris, and Gillian Anderson.

[40] Well known in philosophy and mathematics, the so-called paradox of Tristram Shandy was introduced by Bertrand Russell in his book The Principles of Mathematics to evidentiate the inner contradictions that arise from the assumption that infinite sets can have the same cardinality—as would be the case with a gentleman who spends one year to write the story of one day of his life, if he were able to write for an infinite length of time.

We have had a front view of that marvellous theatre, the soul; the arrangements of lights and the perspective have not failed in their effects, and while we imagined that we were gazing upon the infinite, our own hearts have been exalted with a sense of infinity and poetry.

In Anthony Trollope's novel Barchester Towers, the narrator speculates that the scheming clergyman, Mr Slope, is descended from Dr Slop in Tristram Shandy (the extra letter having been added for the sake of appearances).

Christopher Morley, editor of The Saturday Review of Literature, wrote a preface to the Limited Editions Club issue of Sterne's classic.

In it, Walter Shandy attempts to build an addition engine, while Toby and Corporal Trim re-enact in miniature Wellington's great victory at Vitoria.