Troilus

It is a common practice for those writing about the story of Troilus as it existed in ancient times to use both literary sources and artifacts to build up an understanding of what seems to have been the most standard form of the myth and its variants.

[6] The brutality of this standard form of the myth is highlighted by commentators such as Alan Sommerstein, an expert on ancient Greek drama, who describes it as "horrific" and "[p]erhaps the most vicious of all the actions traditionally attributed to Achilles.

[26] Sommerstein attempts a reconstruction of the plot of the Troilos, in which the title character is incestuously in love with Polyxena and tries to discourage the interest in marrying her shown by both Achilles and Sarpedon, a Trojan ally and son of Zeus.

[33]This passage is explained in the Byzantine writer John Tzetzes' scholia as a reference to Troilus seeking to avoid the unwanted sexual advances of Achilles by taking refuge in his father Apollo's temple.

[35] This begins to build up the elements of the version of Troilus' story given above: he is young, much loved and beautiful; he has divine ancestry, is beheaded by his rejected Greek lover and, we know from Homer, had something to do with horses.

Ancient Greek art, as found in pottery and other remains, frequently depicts scenes associated with Troilus' death: the ambush, the pursuit, the murder itself and the fight over his body.

[74] A crater contemporary with this shows Achilles at the altar holding the naked Troilus upside down while Hector, Aeneas and an otherwise unknown Trojan Deithynos arrive in the hope of saving the youth.

Some pottery shows Achilles, already having killed Troilus, using his victim's severed head as a weapon as Hector and his companions arrive too late to save him; some includes the watching Athena, occasionally with Hermes.

The age of the victim is often an indicator of which story is being told and the relative small size here might point towards the death of Astyanax, but it is common to show even Troilus as much smaller than his murderer, (as is the case with the kylix pictured to the above right).

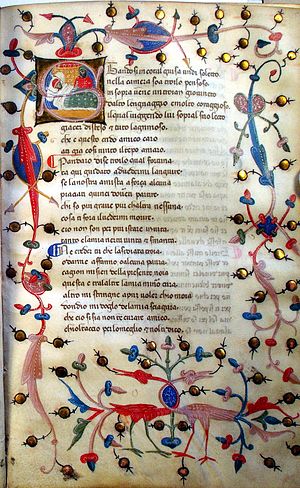

For medieval writers, the two most influential ancient sources on the Trojan War were the purported eye-witness accounts of Dares the Phrygian, and Dictys the Cretan, which both survive in Latin versions.

However, it was two of their contemporaries, Benoît de Sainte-Maure in his French verse romance and Guido delle Colonne in his Latin prose history, both also admirers of Dares, who were to define the tale of Troy for the remainder of the medieval period.

[79] In Dares, Troilus is the youngest of Priam's royal sons, bellicose when peace or truces are suggested and the equal of Hector in bravery, "large and most beautiful... brave and strong for his age, and eager for glory.

Joseph of Exeter, in his Daretis Phrygii Ilias De bello Troiano (The Iliad of Dares the Phrygian on the Trojan War), describes the character as follows: The limbs of Troilus expand and fill his space.

He is "the wall of his homeland, Troy's protection, the rose of the military...."[108] The list of Greek leaders Troilus wounds expands in the various re-tellings of the war from the two in Dares to also include Agamemnon, Diomedes and Menelaus.

Eventually, so many of his followers are killed that he decides to rejoin the battle leading to Troilus' death and, in turn, to Hecuba, Polyxena and Paris plotting Achilles' murder.

His version (a history) is more moralistic and less touching, removing the psychological complexity of Benoît's (a romance) and the focus in his retelling of the love triangle is firmly shifted to the betrayal of Troilus by Briseida.

Troilus mocks the lovelorn glances of other men who put their trust in women before falling victim to love himself when he sees Cressida, here a young widow, in the Palladium, the temple of Athena.

More a Hamlet than a Romeo,[140] by the end of the play his illusions of love shattered and Hector dead, Troilus might show signs of maturing, recognising the nature of the world, rejecting Pandarus and focusing on revenge for his brother's death rather than for a broken heart or a stolen horse.

[145] Troilus' actions are subject to the gaze and commentary of both the venal Pandarus and of the cynical Thersites who tells us: ...That dissembling abominable varlet Diomed has got that same scurvy, doting, foolish knave's sleeve of Troy there in his helm.

[154] Boitani sees the two World Wars and the 20th century's engagement "in the recovery of all sorts of past myths"[155] as contributing to a rekindling of interest in Troilus as a human being destroyed by events beyond his control.

[158] Love and death, the latter either as a tragedy in itself or as an epic symbol of Troy's own destruction, therefore, are the two core elements of the Troilus myth for the editor of the first book-length survey of it from ancient to modern times.

[155] Belief in the medieval tradition of the Trojan War that followed Dictys and Dares survived the Revival of Learning in the Renaissance and the advent of the first English translation of the Iliad in the form of Chapman's Homer.

Then, in "some of the most powerful and hair-raising" words ever written on Troilus' death,[165] Wolf describes how Achilles enters the temple, caresses then half-throttles the terrified boy, who lies on the altar, before finally beheading him like a sacrificial victim.

After his death, the Trojan council propose that Troilus be officially declared to have been twenty in the hope of avoiding the prophecy about him but Priam, in his grief, refuses as this would insult his dead son further.

The major difficulty is the emotional dissatisfaction resulting from how the tale, as originally invented by Benoît, is embedded into the pre-existing narrative of the Trojan War with its demands for the characters to meet their traditional fates.

[171] Christopher Hassall's libretto blends elements of Chaucer and Shakespeare with inventions of its own arising from a wish to tighten and compress the plot, the desire to portray Cressida more sympathetically and the search for a satisfactory ending.

The closed window, The river of Styx, the wall of limitation Beyond which the word beyond loses its meaning, Are the fertilising paradox, the grille That, severing, joins, the end to make us begin Again and again, the infinite dark that sanctions Our growing flowers in the light, our having children...

[179] The general tone is one of high comedy combined with a "genuine atmosphere of doom, danger and chaos" with the BBC website listing A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum as an inspiration together with Chaucer, Shakespeare, Homer and Virgil.

In a reversal of the usual story, he is able to avenge Hector by killing Achilles: they meet outside Troy and the Greek hero, despite being more than a match for the young Trojan, catches his heel on some vegetation and stumbles.

The story was originally intended to end more conventionally, with "Cressida", despite her love for him, apparently abandoning him for "Diomede", but the producers declined to renew co-star Maureen O'Brien's contract, requiring that her character Vicki be written out.