Trotskyism in Vietnam

[2] Following the bloody suppression of the Yên Bái mutiny, their leader Tạ Thu Thâu expressed their view of the revolution in Indochina in the pages of the Left Opposition La Verité (May and June issues, 1930).

"[3] For organising protests against the execution of Yên Bái insurgent leaders, in May 1930 Tạ Thu Thâu and eighteen of his compatriots were arrested and deported back to Cochinchina.

Once considered "the theoretician of the Vietnamese contingent in Moscow,"[6] Tường was calling for a new "mass-based" party arising directly "out of the real struggle of the proletariat of the cities and countryside.

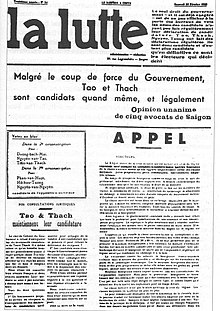

They put forward a common "Workers' List" and briefly published a newspaper (in French to get around the print restrictions on Vietnamese), La Lutte (The Struggle) to rally support for it.

In spite of the restricted franchise, two of this Struggle group were elected (although denied their seats), the independent (later Trotskyist) Tran Van Thach and Nguyễn Văn Tạo.

In 1934 the La Lutte the collaboration was revived on the basis of a formal Party-Oppositionist entente: "struggle oriented against the colonial power and its constitutionalist allies, support of the demands of workers and peasants without regard to which of the two groups they were affiliated with, diffusion of classic Marxist thought, [and] rejection of all attacks against the USSR and against either current.

[11] At the end of 1935, unwilling to enter into a further accommodation with the "Stalinists, " the October Group of Hồ Hữu Tường, Lu Sanh Hanh and of Ngô Văn (the chronicler of the Trotskyist struggle in later exile) formed the core of the League of Internationalist Communists for the Construction of the Fourth International (Chanh Doan Cong San Quoc Te Chu Nghia--Phai Tan Thanh De Tu Quoc).

The League maintained a "complete system of clandestine and legal publications"[12] including its own weekly "organ of proletarian defence and Marxist combat", Le Militant (this carried Lenin's Testament with its warnings against Stalin, and Trotsky's polemics against the Popular Front),[13] topical pamphlets in both French and Vietnamese (including Ngô Văn's denunciation of the Moscow Trials) and an agitational bulletin, Thay Tho (Wage and Salary Workers).

In 1937–38, this northern group had put out a weekly, Thoi Dam (Chronicles), with a call to workers and peasants to set up "unified people's committees in the struggle for rice, freedom and democracy.

[16] While the Stalinists urged respect for the law to the peasants who had begun to agitate in a violent manner against direct and indirect taxes and for a reduction in rents, the League's call for "action committees" was met with widespread arrests.

Together with the lengthening shadow of the Moscow Trials (obliging the Party loyalists to denounce their erstwhile Trotskyite colleagues as "the twin brothers of fascism"), growing disagreement over the new PCF-supported Popular Front government in France ensured a split.

[19] The La Lutte group had entered its own Popular Front known under the name of the Indo Chinese Congress Movement (Phong-tiao-Dong-duong-Dai-hoi) with the bourgeois Constitutionalist Party, in order to draw up demands relating to the political, economic and social reforms that were to be presented to the new government in Paris.

Colonial Minister Marius Moutet, a Socialist commented that he had sought "a wide consultation with all elements of the popular [will]," but with "Trotskyist-Communists intervening in the villages to menace and intimidate the peasant part of the population, taking all authority from the public officials," the necessary "formula" had not been found.

[21] Thâu's motion attacking the Popular Front for betraying the promises of reforms in the colonies was rejected by the PCI faction and in June 1937 the Stalinists withdrew from La Lutte.

[22] Labour unrest culminated in the general strike of 1937 that included workers in the arsenal at Saigon, of the Trans-Indo Chinese Railway (Saigon-Hanoi), the Tonkin miners and the coolies of the rubber plantations.

[20] In April 1939, together with the Octobrists, the now wholly Trotskyist La Lutte group celebrated what a reviewer of Ngô Văn's later account[23] describes as "the only instance prior to 1945 in which the politics of 'permanent revolution' oriented to worker and peasant opposition to colonialism won out, however ephemerally, against Stalinist 'stage theory' in a public arena.

"[24] In elections to the colonial Cochinchina Council a "United Workers and Peasants" slate, led by Tạ Thu Thâu, triumphed over both the Communist Party's Democratic Front and the "bourgeois" Constitutionalists with fully 80 per cent of the vote.

"[26] The Democratic platform, with its calls for national unity and relatively modest demands for constitutional change, was presented by a party whose leading cadres "emphasised much more the exterior development of capitalism", "used the word 'imperialism' much more often in their discussions," talked about "nonequivalent exchange", and of "the continuing feudal nature of Vietnamese society.

Their rule had the calculated appearance of being external to a still extant indigenous culture, and allowed greater play to the idea of a national society that might be mobilised against the foreign overseer.

In Cochinchina, the Party obliged with a peasant revolt in November 1940 that the new Japanese occupiers left pro-Petain French colonial authorities free to suppress.

They formed the International Communist League (Vietnam) (ICL), or less formally as The Fourth Internationalist Party (Trăng Câu Đệ Tứ Đảng).

Assemble under the banner of the party of the Fourth International!Opportunity for open political struggle returned with the formal surrender of the occupying Japanese on 15 August 1945.

Embracing the "bourgeois" nationalist VNQD, the syncretic Hoa Hao and Cao Dai sects and the Jeunesse d'Avant-Garde/Thanh Nien Tienphong [the Vanguard Youth, initially mobilized by the French], it was viewed by Japanese as a counterweight to the PCI's new formed Front for the Independence of Vietnam, the Viet Minh.

The lack of connection was made "painfully clear" when Ngô Văn and his comrades found they had "no way of finding out what was happening" following reports that in the Hòn Gai-Cẩm Phả coal region north of Haiphong, under the indifferent gaze of the defeated Japanese 30,000 workers had elected councils to run mines, public services and transport, and were applying the principle of equal wages for all types of work, whether manual or intellectual.

When, for the declared purpose of disarming the Japanese, the Committee accommodated the landing and strategic positioning of British and British-Indian troops, rival political groups turned out in force.

[34] Forsaking his revolutionary principles, Hồ Hữu Tường took refuge with the French Bảo Đại associated government (later he became a deputy in the "farcical 'opposition'" under the military regime of Nguyen Van Thieu).

[14] But "harassed by the Sûreté in the city and denied refuge in a countryside dominated by the two terrors, the French and the Viet-Minh,"[51] most ICL survivors appear to be those who, like Ngô Văn, sought exile in France.

[52] In what, presumably, was a still smaller exile publication, Thieng Tho (Workers' Voice), Ngô Văn wrote an opinion piece under the name Dong Vu (30 October 1951) "Prolétaires et paysans, retournez vos fusils!"

It is what Robert Alexander recounts as "the passion, effort and attention paid by Trotskyists of virtually all countries and all factions to support of the Stalinist side during the long and cruel Vietnam War, which in one form or another went on for thirty years, from 1945 to 1975.