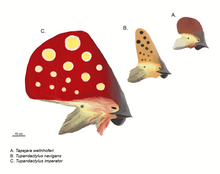

Tupandactylus

Tupandactylus (meaning "Tupan finger", in reference to the Tupi thunder god) is a genus of tapejarid pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous Crato Formation of Brazil.

The holotype specimen is MCT 1622-R, a skull and partial lower jaw, found in the Crato Formation, dating to the boundary of the Aptian-Albian stages of the early Cretaceous period, about 112 Ma ago.

Soft tissue impressions also show that the small bony crests were extended by a much larger structure made of a keratinous material.

[6] Beginning in 2006, several researchers, including Kellner and Campos (who named Tupandactylus), had found that the three species traditionally assigned to the genus Tapejara (T. wellnhofferi, T. imperator, and T. navigans) are in fact distinct both in anatomy and in their relationships to other tapejarid pterosaurs, and thus needed to be given new generic names.

Therefore, because both sets of authors used imperator as the type, Ingridia is considered a junior objective synonym of Tupandactylus.

[8] It was not until 2011 that T. navigans was formally reclassified in the genus Tupandactylus, in a subsequent study supporting the conclusions of Unwin and Martill in 2007.

[10][11] A research team consisting of paleontologist Sankar Chatterjee of Texas Tech University, aeronautical engineer Rick Lind of the University of Florida, and their students Andy Gedeon and Brian Roberts sought to mimic the physical and biological characteristics of this pterosaur—skin, blood vessels, muscles, tendons, nerves, cranial plate, skeletal structure, and more—to develop an unmanned aerial vehicle that not only flies but also walks and sails just like the original, to be called a Pterodrone.

[12] The large, thin rudder-like sail on its head functioned as a sensory organ that acted similarly to a flight computer in a modern-day aircraft and also helped with the animal's turning agility.

It has been noted that tapejarids had short wings, about as suited for soaring as those of Galliformes, which are indeed consistent with adaptations for terrestriality and climbing.