Shroud of Turin

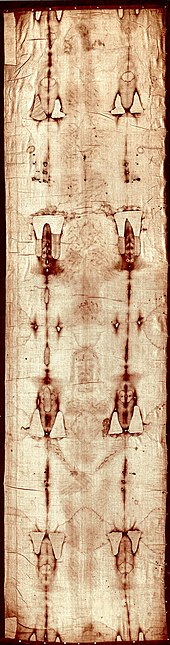

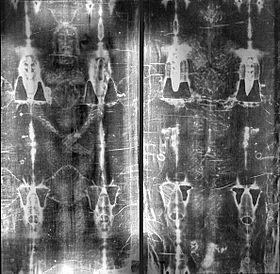

[23] The image in faint straw-yellow colour on the crown of the cloth fibres appears to be of a man with a beard, moustache, and shoulder-length hair parted in the middle.

[33] In 1353 the village of Lirey, in north-central France, was enriched with a small collegiate church endowed by the local feudal lord, a knight named Geoffroi de Charny.

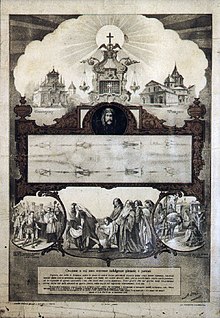

[10] Around 1355, the dean of the chapter of Lirey, Robert de Caillac, began exhibiting in the church a long fabric that bore an image of the mangled body of Jesus.

[32][34] Clement issued a bull allowing the canons of Lirey to continue exhibiting the Shroud as long as they made it clear that it was an artistic representation of the passion of Jesus and not a true relic.

[41][42] Roberto Gottardo of the diocese of Turin stated that for the first time they had released high definition images of the Shroud that can be used on tablet computers and can be magnified to show details not visible to the naked eye.

[41] As this rare exposition took place, Pope Francis issued a carefully worded statement which urged the faithful to contemplate the Shroud with awe but, like most of his predecessors, he "stopped firmly short of asserting its authenticity".

[citation needed] The Gospels of Matthew,[47] Mark,[48] and Luke[49] state that Joseph of Arimathea wrapped the body of Jesus in a linen shroud "sindon" and placed it in a new tomb.

On the whole, either the Evangelist John must have given a false account, or every one of them must be convicted of falsehood, thus making it manifest that they have too impudently imposed on the unlearned.Although pieces said to be of burial cloths of Jesus are held by at least four churches in France and three in Italy, none has gathered as much religious following as the Shroud of Turin.

[54] The religious beliefs and practices associated with the shroud predate historical and scientific discussions and have continued in the 21st century, although the Catholic Church has never passed judgment on its authenticity.

Today the Catholic devotions to the Holy Face of Jesus are usually associated with the negative image of the Shroud of Turin, as first captured in Secondo Pia's 1898 photograph.

However, these devotions predate Pia's image, having been established in 1844 by the Carmelite nun Marie of St Peter, based on depictions of Jesus before his crucifixion and associated with the tradition of the Veil of Veronica.

The modern devotion to the Holy Face centered on the negative photographic image from the Shroud of Turin derives principally from an Italian nun born in Milan, Maria Pierina De Micheli, who reported having visions of Jesus starting in 1936.

[68][69] His successor, Pope Benedict XVI, called it an "icon written with the blood of a whipped man, crowned with thorns, crucified and pierced on his right side".

In his address at the Turin Cathedral on Sunday 24 May 1998 (the occasion of the 100th year of Secondo Pia's 28 May 1898 photograph), he said: "The Shroud is an image of God's love as well as of human sin...

The imprint left by the tortured body of the Crucified One, which attests to the tremendous human capacity for causing pain and death to one's fellow man, stands as an icon of the suffering of the innocent in every age.

"[43][44] In his carefully worded statement, Pope Francis urged the faithful to contemplate the shroud with awe, but "stopped firmly short of asserting its authenticity".

A variety of scientific theories regarding the shroud have since been proposed, based on disciplines ranging from chemistry to biology and medical forensics to optical image analysis.

McCrone concluded that the Shroud's body image had been painted with a dilute pigment of red ochre (a form of iron oxide) in a collagen tempera (i.e., gelatin) medium, using a technique similar to the grisaille employed in the 14th century by Simone Martini and other European artists.

McCrone also found that the "bloodstains" in the image had been highlighted with vermilion (a bright red pigment made from mercury sulfide), also in a collagen tempera medium.

[81] In his book Ray Rogers states that Anderson, who was McCrone's Raman microscopy expert, concluded that the samples acted as organic material when he subjected them to the laser.

[83] He also argued that the members of STURP lacked relevant expertise in the chemical microanalysis of historical artworks and that their non-detection of pigment in the Shroud's image was "consistent with the sensitivity of the instruments and techniques they used.

[85][86] This dating is also slightly more recent than that estimated by art historian W. S. A. Dale, who postulated on artistic grounds that the shroud is an 11th-century icon made for use in worship services.

[87] Some proponents for the authenticity of the shroud have attempted to discount the radiocarbon dating result by claiming that the sample may represent a medieval "invisible" repair fragment rather than the image-bearing cloth.

[100] McCrone (see painting hypothesis) showed that these contain iron oxide, and theorised that its presence was likely due to simple pigment materials used in medieval times.

In 2018, an experimental Bloodstain Pattern Analysis (BPA) was performed to study the behaviour of blood flows from the wounds of a crucified person, and to compare this to the evidence on the Turin Shroud.

[5] McCrone also argued that the current image on the shroud may be fainter than the original painting, due to the rubbing off of the ochre pigment from the tops of the exposed linen fibers over the course of several centuries of handling and exhibition of the fabric.

[83]: 106 In 2009, Luigi Garlaschelli, professor of organic chemistry at the University of Pavia, stated that he had made a full size reproduction of the Shroud of Turin using only medieval technologies.

Such claimants tend to draw upon the wisdom of hindsight to project a distorted historical perspective, wherein their cases rest upon a particular concatenation of procedures which is exceedingly improbable; and their 'proofs' amount only to demonstrating (none too faithfully) that it was not totally impossible."

[143] Although the Pray Codex predates the Shroud of Turin, some of the assumed features of the drawing, including the four L-shaped holes on the coffin lid, have pointed some people towards a possible attempted representation of the linen cloth.

[145][146][147] However, STURP member Alan Adler has stated that this theory is not generally accepted as scientific, given that it runs counter to the laws of physics,[145] while agreeing that the darkening of the fabric could be produced by exposure to light (and predicting that despite the fact that the Shroud is normally stored in darkness and rarely displayed, it will eventually become darker in the future).