Turkish coffee

[15]: 14 The coffee tree was first cultivated commercially in the Yemen, having been introduced there from the rainforests of Ethiopia[nb 1] where it grew wild.

[16] For a long time[17]: 85 Yemenis had a world monopoly on the export of coffee beans[16] (according to Carl Linnaeus, by deliberately destroying their ability to germinate).

[18]: 102 For nearly a century (1538–1636), the Ottoman Empire controlled the southern coastal region of the Yemen, notably its famous coffee port Mocha.

[15]: 163 In the 18th century Egypt was the richest province of the Ottoman Empire, and the chief commodity it traded was Yemeni coffee.

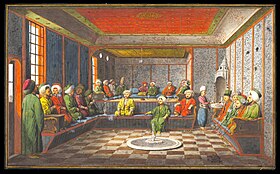

[21]: 744 Ignatius d'Ohsson described for French readers the Turkish method of brewing coffee (Tableau Général de l'Empire Othoman, 1789).

His description, translated in this note,[22] closely resembles the present day version, including the production of foam.

Yemenis may have been the first to consume coffee as a hot beverage (instead of chewing the bean, or adding it to solid food)[17]: 88 and the earliest social users were probably Sufi mystics in that region who needed to stay awake for their nocturnal vigils.

[34]: 90 Under Sultan Murad IV those found keeping a coffeehouse were cudgelled for a first offence, sewn in a bag and thrown into the Bosphorus for a second.

(Similarly, the government of Charles II of England tried to suppress coffee houses as seditious gatherings - the ban lasted a few days[28]: 14 - and, much later, the republican government of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk tried to prohibit or discourage coffeehouses in Turkish villages, saying they were places where men gathered to waste their time).

To demonstrate the civility of their rule, they built magnificent coffeehouses in newly conquered parts of the Ottoman Empire.

[39]: 209 However, most early modern Europeans did not like coffee,[39]: 194, 200 [36]: 4 which is an acquired taste,[40]: 5–6 and especially they did not like the black, bitter Turkish version.

[39]: 215 Coffee did not become a popular beverage until it was altered to appeal to European palates and its price drastically lowered, as follows.

[39]: 213 [40]: 76 They were followed by the French, who planted a tree at the Jardin des Plantes de Paris; it has been claimed that "This tree was destined to be the progenitor of most of the coffee of the French colonies, as well as those of South America, Central America, and Mexico",[37]: 5–9 [38]: 286 i.e. most of the coffee in the world, though it has been called "a neat story".

[43] Especially in France there was a craze for things Turkish: fashion plates depicted aristocratic ladies taking coffee while dressed as sultanas, attended by servants in Moorish costume.

Its medical value was stressed: it became popular in France when doctors advised café au lait was good for the health.

[39]: 201, 203–208, 211 In England, the earliest advertisement (1652) for a coffee house — owned by Pasqua Rosée, an Armenian from Ragusa (modern Dubrovnik) — claimed that Turkish people "are not troubled with the Stone, Gout, Dropsie, or Scurvey" and "their skins are exceedingly cleer and white".

Despite this, Rosée's product was weak enough to be drunk a half pint (485 ml) at a time on an empty stomach,[37]: 53, 55 not an attribute of real Turkish coffee.

If there were 'Turkish' coffeehouses in Oxford or Paris, the cited historical sources do not show they were serving coffee made in the Turkish manner.

"The coffeehouse and café, far from being English and French creations, were at heart an import from Mecca, Cairo, and Constantinople",[39]: 198 a topic outside the scope of this article.

[41]: 13 In the 20th century, especially in wartime and the 1950s, shortages in Turkey meant that coffee was scarcely available for years at a time, or was adulterated with chickpeas and other substances.

'"[14]: 71 There is controversy about its name e.g. in some ex-Ottoman dependencies, mostly due to nationalistic feelings or political rivalry with Turkey.

Originally, “dibek” referred to two slightly indented stones used to crush roasted coffee beans by rubbing them together.

The roasted beans are crushed in the dibek using a wooden or iron hammer until they reach the desired size.

This method preserves the aromatic oils in the coffee, enhancing its flavor and helping to maintain its foam during cooking.

Additionally, Dibek Coffee is highlighted as a gastronomic representative of İzmir and its surrounding areas, including Urla, Seferihisar, Sığacık, Çeşme, Alaçatı, and nearby villages.

A deviation from the Turkish preparation is that when the water reaches its boiling point, a small amount is saved aside for later, usually in a coffee cup.

Everything is put back on the heat source to reach its boiling point again, which only takes a couple of seconds since the coffee is already very hot.

[66] Coffee drinking in Bosnia is a traditional daily custom and plays an important role during social gatherings.