Twelfth siege of Gibraltar

The defenders were able to hold off the numerically superior besieging force through exploiting Gibraltar's geography and the small town's fortifications, though they were frequently short of manpower and ammunition.

Sea power proved crucial, as the French navy sought unsuccessfully to prevent the Grand Alliance shipping in fresh troops, ammunition and food.

It was not only, as a later Spanish writer put it, "the first town in Spain to be dismembered from the domination of King Philip and forced to recognise Charles,"[3] but it also potentially had great value as an entry point for the Grand Alliance armies.

Its possibilities were recognised immediately by the Alliance forces' leader Prince George of Hesse-Darmstadt, who told Charles in a letter of September 1704, that Gibraltar was "a door through which to enter Spain".

From there, it was a relatively short distance to Seville, where the Habsburg claimant Charles could be proclaimed king, following which the Alliance could march to Madrid and finish the war.

[4] The town was garrisoned by a motley assortment of Alliance forces, consisting of around 2,000 British and Dutch marines, 60 gunners and several hundred Spanish, mostly Catalans, followers of Charles of Austria.

[7] The Anglo-Dutch fleet was hampered by a shortage of shot and gunpowder, much of which had already been used in bombarding Gibraltar during the operation to capture it, and Sir George Byng's squadron was forced to pull back when it ran out of ammunition.

The Spanish had already mobilised their forces and at the start of September the Marquis of Villadarias, the captain-general of Andalusia, arrived in the vicinity of Gibraltar with an army of 4,000 men.

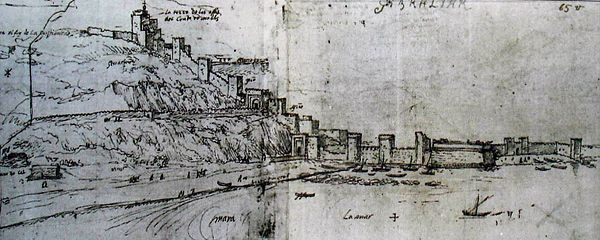

The north side of the Rock of Gibraltar presents a vertical cliff; the only access to the town was via a narrow strip, only about 400 feet (120 m) wide, which was blocked by the heavily fortified curtain wall known as the Muralla de San Bernardo (later the Grand Battery).

[11] Although Hesse was confident that he would be able to hold Gibraltar against the numerically superior Franco-Spanish force, he was undermined by political disputes between the Habsburg and English commanders.

The two men had fought on opposite sides during the Irish campaign of William III; the Protestant Fox had gone on to serve Queen Anne, while the Catholic Nugent had joined the service of Charles of Austria.

This brought the number of soldiers under Villadarias's command to some 7,000, which Hesse estimated consisted of eight Spanish and six French battalions of foot plus nine cavalry squadrons.

As the accused were Habsburg subjects, a court-martial consisting of British and Dutch officers – who did not owe allegiance to Charles – was convened to adjudicate the case.

They made it to the top of the Rock, reaching its southernmost peak near where O'Hara's Battery stands today, and descended part-way down the west side where they sheltered overnight in St. Michael's Cave.

At daybreak they climbed the Philip II Wall, which extends up the west side of the Rock, and killed the English sentries in the lookout point at Middle Hill.

Although the Bourbons had the advantage of height, they were effectively trapped against the precipice of the Rock and only had three rounds of ammunition each, as a result of travelling light; they had not come prepared for a pitched battle.

[19] At the same time, Sandoval, with his remaining regulars and miquelets, charged upon the bulk of the assaulting force from one flank, while Heinrich von Hesse attacked from the other side.

[16][18] The other 1,500 members of the Spanish force did not even set off to support the attack because, after the first 500 had left, Admiral Leake's squadron was sighted entering the bay with 20 ships.

Hesse's relief at Leake's timely arrival was evident in the letter that he sent the admiral after the battle, thanking him for turning up just as "the enemy were attacking us that very night of your entrance in many places at once with a great number of men.

"[20] Leake had not brought many supplies to Gibraltar but provided what he could, and loaned Hesse the fleet's skilled manpower, of which the confederate garrison was desperately short.

Captain Joseph Bennett, an engineer whom Leake had brought with him, helped to bolster the fortifications but earned the wrath of some in the garrison, who felt that Gibraltar should be abandoned.

[22] He wrote to a friend on 6 December to tell him that "many officers had a design to quit the place and blow up the works but I always opposed them, and mentioned the garrison could be kept with the number of 900 men we had, and no more, as I believe you will have an [account] of.

Their living conditions were increasingly grim; their shoes had worn out and many men wore makeshift sandals made from hay and straw.

[25] The Bourbon Spanish and French land force continued to bombard Gibraltar, inflicting further damage on the town's somewhat weak fortifications but were unable to make any progress against the reinforced garrison.

[25] Relations steadily worsened between the Spanish and French components of the besieging force, a trend that was exacerbated by the lack of progress they were making, the appalling conditions they were enduring in the open and the steady stream of casualties being caused by the counter-bombardment and outbreaks of epidemic disease.

On 7 February, he sent 1,500 French, Spanish and Irish troops to seize the Round Tower,[26] an outlying fortification on the cliff face above the present Laguna Estate.

Their morale improved somewhat when Admiral Bernard Desjean, Baron de Pointis sailed into the bay on 26 February with a force of 18 men-of-war from Cadiz.

"[2] With the French having gone home, Villadarias resumed command and began to convert the siege into a blockade by pulling back from the isthmus and removing his cannon.

The following day, a larger party, protected by grenadiers, resumed the work of demolishing the Spanish batteries without further opposition, marking the end of the siege.

Various territorial exchanges were agreed: although Philip V retained the Spanish overseas empire, he ceded the Southern Netherlands, Naples, Milan, and Sardinia to Austria; Sicily and some Milanese lands to Savoy; and Gibraltar and Menorca to Great Britain.