Twin study

[2] Twins have been of interest to scholars since early civilization, including the early physician Hippocrates (5th century BCE), who attributed different diseases in twins to different material circumstances,[3] and the stoic philosopher Posidonius (1st century BCE), who attributed such similarities to shared astrological circumstances.

[5] Both Gustav III and his father had read and been strongly influenced by a 1715 treatise from a French physician on the dangers of what would later be identified as caffeine in tea and coffee.

[6] After assuming the throne in 1771 the king became strongly motivated to demonstrate to his subjects that coffee and tea had deleterious effects on human health.

To this end he offered to commute the death sentences of a pair of twin murderers if they participated in a primitive clinical trial.

The age of the coffee-drinking twin at his death is unknown, as both doctors assigned by the king to monitor this study predeceased him.

[9] This factor was still not understood when the first study using psychological tests was conducted by Edward Thorndike (1905) using fifty pairs of twins.

This allowed him to account for the oversight that had stumped Fisher, and was a staple in twin research prior to the advent of molecular markers.

Wilhelm Weinberg and colleagues in 1910 used the identical-DZ distinction to calculate respective rates from the ratios of same- and opposite-sex twins in a maternity population.

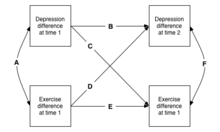

[17][18] The basic logic of the twin study can be understood with very little mathematical knowledge beyond an understanding of the concepts of variance and thence derived correlation.

Like all behavior genetic research, the classical twin study begins by assessing the variance of behavior (called a phenotype by geneticists) in a large group, and attempts to estimate how much of this is due to: Typically these three components are called A (additive genetics) C (common environment) and E (unique environment); hence the acronym ACE.

It is also possible to examine non-additive genetics effects (often denoted D for dominance (ADE model); see below for more complex twin designs).

Research is typically carried out using Structural equation modeling (SEM) programs such as OpenMx capable in principle of handling all sorts of complex pedigrees.

Beginning in the 1970s, research transitioned to modeling genetic, environmental effects using maximum likelihood methods (Martin & Eaves, 1977).

[23] SEM programs such as OpenMx[24] and other applications suited to constraints and multiple groups have made the new techniques accessible to reasonably skilled users.

[27][28][29] A special ability to test this assumption occurs where parents believe their twins to be non-identical when in fact they are genetically identical.

Studies of a range of psychological traits indicate that these children remain as concordant as MZ twins raised by parents who treated them as identical.

[30] Molecular genetic methods of heritability estimation have tended to produce lower estimates than classical twin studies due to modern SNP arrays not capturing the influence of certain types of variants (e.g., rare variants or repeat polymorphsisms), though some have suggested it is because twin studies overestimate heritability.

[41] Studies in plants or in animal breeding allow the effects of experimentally randomized genotypes and environment combinations to be measured.

For example, in identical and fraternal twins shared environment and genetic effects are not confounded, as they are in non-twin familial studies.

[18] Twin studies are thus in part motivated by an attempt to take advantage of the random assortment of genes between members of a family to help understand these correlations.

Adoption designs are a form of natural experiment that tests norms of reaction by placing the same genotype in different environments.

The variance partitioning of the twin study into additive genetic, shared, and unshared environment is a first approximation to a complete analysis taking into account gene–environment covariance and interaction, as well as other non-additive effects on behavior.

An initial limitation of the twin design is that it does not afford an opportunity to consider both Shared Environment and Non-additive genetic effects simultaneously.

Addressing this limit requires incorporating adoption models, or children-of-twins designs, to assess family influences uncorrelated with shared genetic effects.

[52][53] On this basis, critics contend that twin studies tend to generate inflated or deflated estimates of heritability due to biological confounding factors and consistent underestimation of environmental variance.

[50][54] Other critics take a more moderate stance, arguing that the equal environments assumption is typically inaccurate, but that this inaccuracy tends to have only a modest effect on heritability estimates.

Statistical critiques argue that heritability estimates used for most twin studies rest on restrictive assumptions that are usually not tested, and if they are, they are often contradicted by the data.

Modern twin methods based on structural equation modeling are not subject to the limitations and heritability estimates such as those noted above are mathematically impossible.

Artificial induction of ovulation and in vitro fertilization-embryo replacement can also give rise to fraternal and identical twins.

Measured studies on the personality and intelligence of twins suggest that they have scores on these traits very similar to those of non-twins (for instance Deary et al. 2006).