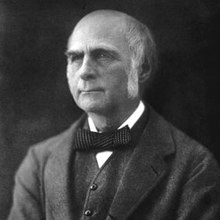

Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton FRS FRAI (/ˈɡɔːltən/; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911) was an English polymath and the originator of eugenics during the Victorian era; his ideas later became the basis of behavioural genetics.

[6] As the initiator of scientific meteorology, he devised the first weather map, proposed a theory of anticyclones, and was the first to establish a complete record of short-term climatic phenomena on a European scale.

[11][12] Galton was born at "The Larches", a large house in the Sparkbrook area of Birmingham, England, built on the site of "Fair Hill", the former home of Joseph Priestley, which the botanist William Withering had renamed.

Both Erasmus Darwin and Samuel Galton were founding members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham, which included Matthew Boulton, James Watt, Josiah Wedgwood, Joseph Priestley and Richard Lovell Edgeworth.

In 1850 he joined the Royal Geographical Society, and over the next two years mounted a long and difficult expedition into then little-known South West Africa (now Namibia).

Galton was a polymath who made important contributions in many fields, including meteorology (the anticyclone and the first popular weather maps), statistics (regression and correlation), psychology (synaesthesia), biology (the nature and mechanism of heredity), and criminology (fingerprints).

Galton devoted much of the rest of his life to exploring variation in human populations and its implications, at which Darwin had only hinted in The Origin of Species, although he returned to it in his 1871 book The Descent of Man, drawing on his cousin's work in the intervening period.

[27] Galton established a research program which embraced multiple aspects of human variation, from mental characteristics to height; from facial images to fingerprint patterns.

In Hereditary Genius, he envisaged a situation conducive to resilient and enduring civilisation as follows: The best form of civilization in respect to the improvement of the race, would be one in which society was not costly; where incomes were chiefly derived from professional sources, and not much through inheritance; where every lad had a chance of showing his abilities, and, if highly gifted, was enabled to achieve a first-class education and entrance into professional life, by the liberal help of the exhibitions and scholarships which he had gained in his early youth; where marriage was held in as high honor as in ancient Jewish times; where the pride of race was encouraged (of course I do not refer to the nonsensical sentiment of the present day, that goes under that name); where the weak could find a welcome and a refuge in celibate monasteries or sisterhoods, and lastly, where the better sort of emigrants and refugees from other lands were invited and welcomed, and their descendants naturalized.

[24] Galton's formulation of regression and its link to the bivariate normal distribution can be traced to his attempts at developing a mathematical model for population stability.

[30] Galton's solution to this problem was presented in his Presidential Address at the September 1885 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, for he was serving at the time as President of Section H: Anthropology.

[39] Darwin challenged the validity of Galton's experiment, giving his reasons in an article published in Nature where he wrote: Now, in the chapter on Pangenesis in my Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication I have not said one word about the blood, or about any fluid proper to any circulating system.

[41]) The statistical techniques that Galton developed (correlation and regression—see below) and phenomena he established (regression to the mean) formed the basis of the biometric approach and are now essential tools in all social sciences.

He stated that the purpose of this laboratory was to "show the public the simplicity of the instruments and methods by which the chief physical characteristics of man may be measured and recorded.

"[42] The laboratory was an interactive walk-through in which physical characteristics such as height, weight, and eyesight, would be measured for each subject after payment of an admission fee.

First, they would fill in a form with personal and family history (age, birthplace, marital status, residence, and occupation), then visit stations that recorded hair and eye colour, followed by the keenness, colour-sense, and depth perception of sight.

Although the laboratory did not employ any revolutionary measurement techniques, it was unique because of the simple logistics of constructing such a demonstration within a limited space, and because of the speed and efficiency with which all the necessary data were gathered.

[43] After the conclusion of the International Health Exhibition, Galton used these data to confirm in humans his theory of linear regression, posed after studying sweet peas.

James Surowiecki[52] uses this weight-judging competition as his opening example: had he known the true result, his conclusion on the wisdom of the crowd would no doubt have been more strongly expressed.

The same year, Galton suggested in a letter to the journal Nature a better method of cutting a round cake by avoiding making radial incisions.

[55] After examining forearm and height measurements, Galton independently rediscovered the concept of correlation in 1888[56][57] and demonstrated its application in the study of heredity, anthropology, and psychology.

[47] In the 1870s and 1880s he was a pioneer in the use of normal theory to fit histograms and ogives to actual tabulated data, much of which he collected himself: for instance large samples of sibling and parental height.

Galton was the first to describe and explain the common phenomenon of regression toward the mean, which he first observed in his experiments on the size of the seeds of successive generations of sweet peas.

Galton[60] developed the following model: pellets fall through a quincunx or "bean machine" forming a normal distribution centred directly under their entrance point.

Others, including Sigmund Freud in his work on dreams, picked up Galton's suggestion that these composites might represent a useful metaphor for an Ideal type or a concept of a "natural kind" (see Eleanor Rosch)—such as Jewish men, criminals, patients with tuberculosis, etc.—onto the same photographic plate, thereby yielding a blended whole, or "composite", that he hoped could generalise the facial appearance of his subject into an "average" or "central type".

However, his technique did not prove useful and fell into disuse, although after much work on it including by photographers Lewis Hine and John L. Lovell and Arthur Batut.

The method of identifying criminals by their fingerprints had been introduced in the 1860s by Sir William James Herschel in India, and their potential use in forensic work was first proposed by Dr Henry Faulds in 1880.

He wrote about the technique (inadvertently sparking a controversy between Herschel and Faulds that was to last until 1917), identifying common pattern in fingerprints and devising a classification system that survives to this day.

His niece appears to have burnt most of the novel, offended by the love scenes, but large fragments survived,[72] and it was published online by University College, London.

The scientists in its thrall claimed this could be achieved by controlling reproduction, policing borders to prevent certain types of immigrants, and locking away "undesirables", including disabled people.