Double-slit experiment

[1] In 1927, Davisson and Germer and, independently, George Paget Thomson and his research student Alexander Reid[2] demonstrated that electrons show the same behavior, which was later extended to atoms and molecules.

[3][4][5] Thomas Young's experiment with light was part of classical physics long before the development of quantum mechanics and the concept of wave–particle duality.

[9] Additionally, the detection of individual discrete impacts is observed to be inherently probabilistic, which is inexplicable using classical mechanics.

Richard Feynman called it "a phenomenon which is impossible […] to explain in any classical way, and which has in it the heart of quantum mechanics.

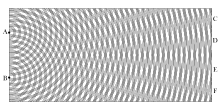

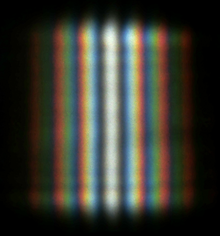

When Thomas Young (1773–1829) first demonstrated this phenomenon, it indicated that light consists of waves, as the distribution of brightness can be explained by the alternately additive and subtractive interference of wavefronts.

However, the later discovery of the photoelectric effect demonstrated that under different circumstances, light can behave as if it is composed of discrete particles.

These seemingly contradictory discoveries made it necessary to go beyond classical physics and take into account the quantum nature of light.

A low-intensity double-slit experiment was first performed by G. I. Taylor in 1909,[23] by reducing the level of incident light until photon emission/absorption events were mostly non-overlapping.

[24][25] In 1974, the Italian physicists Pier Giorgio Merli, Gian Franco Missiroli, and Giulio Pozzi performed a related experiment using single electrons from a coherent source and a biprism beam splitter, showing the statistical nature of the buildup of the interference pattern, as predicted by quantum theory.

[30] Many related experiments involving the coherent interference have been performed; they are the basis of modern electron diffraction, microscopy and high resolution imaging.

[31][32] In 2018, single particle interference was demonstrated for antimatter in the Positron Laboratory (L-NESS, Politecnico di Milano) of Rafael Ferragut in Como (Italy), by a group led by Marco Giammarchi.

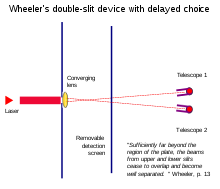

[9] This which-way experiment illustrates the complementarity principle that photons can behave as either particles or waves, but cannot be observed as both at the same time.

[52] An experiment performed in 1987[53][54] produced results that demonstrated that partial information could be obtained regarding which path a particle had taken without destroying the interference altogether.

This "wave-particle trade-off" takes the form of an inequality relating the visibility of the interference pattern and the distinguishability of the which-way paths.

However, commentators such as Svensson[59] have pointed out that there is in fact no conflict between the weak measurements performed in this variant of the double-slit experiment and the Heisenberg uncertainty principle.

[64][65] In 1999, a quantum interference experiment (using a diffraction grating, rather than two slits) was successfully performed with buckyball molecules (each of which comprises 60 carbon atoms).

The total intensity of the far-field double-slit pattern is shown to be reduced or enhanced as a function of the wavelength of the incident light beam.

[69] In 2012, researchers at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln performed the double-slit experiment with electrons as described by Richard Feynman, using new instruments that allowed control of the transmission of the two slits and the monitoring of single-electron detection events.

[19] Hydrodynamic analogs have been developed that can recreate various aspects of quantum mechanical systems, including single-particle interference through a double-slit.

[71] A silicone oil droplet, bouncing along the surface of a liquid, self-propels via resonant interactions with its own wave field.

The droplet's interaction with its own ripples, which form what is known as a pilot wave, causes it to exhibit behaviors previously thought to be peculiar to elementary particles – including behaviors customarily taken as evidence that elementary particles are spread through space like waves, without any specific location, until they are measured.

[76] In 2023, an experiment was reported recreating an interference pattern in time by shining a pump laser pulse at a screen coated in indium tin oxide (ITO) which would alter the properties of the electrons within the material due to the Kerr effect, changing it from transparent to reflective for around 200 femtoseconds long where a subsequent probe laser beam hitting the ITO screen would then see this temporary change in optical properties as a slit in time and two of them as a double slit with a phase difference adding up destructively or constructively on each frequency component resulting in an interference pattern.

If the viewing distance is large compared with the separation of the slits (the far field), the phase difference can be found using the geometry shown in the figure below right.

Modern quantitative versions of the concept allow for a continuous tradeoff between the visibility of the interference fringes and the probability of particle detection at a slit.

[85][86] The Copenhagen interpretation is a collection of views about the meaning of quantum mechanics, stemming from the work of Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Max Born, and others.

The term "Copenhagen interpretation" was apparently coined by Heisenberg during the 1950s to refer to ideas developed in the 1925–1927 period, glossing over his disagreements with Bohr.

Features common across versions of the Copenhagen interpretation include the idea that quantum mechanics is intrinsically indeterministic, with probabilities calculated using the Born rule, and some form of complementarity principle.

[98] David Wallace, another advocate of the many-worlds interpretation, writes that in the familiar setup of the double-slit experiment the two paths are not sufficiently separated for a description in terms of parallel universes to make sense.

[99] An alternative to the standard understanding of quantum mechanics, the De Broglie–Bohm theory states that particles also have precise locations at all times, and that their velocities are defined by the wave-function.

[101] While the model is in many ways similar to Schrödinger equation, it is known to fail for relativistic cases[102] and does not account for features such as particle creation or annihilation in quantum field theory.