Typos of Constans

Ten years later his son, Constantine IV, fresh from a triumph over his Arab enemies and with the predominantly Monophysitic provinces irredeemably lost, called the Third Council of Constantinople.

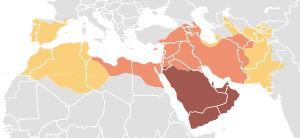

[note 1] High taxes, the power of the landowners over the peasants, and the recently ended war with the Persians were some of the reasons why the Syrians welcomed the change.

In the following three years, the Empire endured four short-lived emperors or usurpers before seventeen-year-old Constans II, grand-son of Heraclius, established himself on the throne of the diminished realm.

[4] Emperor Heraclius spent the last years of his life attempting to find a compromise theological position between the Monophysites and the Chalcedonians.

What he promoted via his Ecthesis was a doctrine which declared that Jesus, whilst he possessed two distinct natures, had only one will; the question of the energy of Christ was not relevant.

Pope Honorius I and the four Patriarchs of the East – Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem – all gave their approval to the doctrine, referred to as Monothelitism, and so it looked as if Heraclius would finally heal the divisions in the church.

His successor Pope John IV also rejected the doctrine completely, leading to a major schism between the eastern and western halves of the Catholic Church.

The threat of imminent invasion increased the local bishops' antipathy to Monophysitism, knowing that its adherents in Syria and Egypt had welcomed the invading Arabs.

A monk named Maximus the Confessor had long carried on a furious campaign against Monotheletism, and in 646 convinced an African council of bishops, all resolutely Chalcedonian, to draw up a manifesto against it.

This they forwarded to the new pope, Theodore I, who in turn wrote to Patriarch Paul II of Constantinople, outlining the heretical nature of the doctrine.

He had just established an uncertain truce with the Arabs, and badly needed to rebuild his forces and to gain the full support of his empire.

[note 2] This edict made it illegal to discuss the topic of Christ possessing either one or two wills, or one or two energies; or even to acknowledge that such a debate was possible.

[17] The Typos goes on to deny people "the licence to conduct any dispute, contention or controversy",[17] explaining that whole matter has been settled by the five previous ecumenical councils "and the straight forwardly plain statements... of the approved holy fathers".

[12] In Rome and the west, the opposition to Monotheletism was reaching fever pitch, and the Typos of Constans did nothing to defuse the situation; indeed it made it worse by implying that either doctrine was as good as the other.

After the synod, Pope Martin wrote to Constans, informing the emperor of its conclusions and requiring him to condemn both the Monothelete doctrine and his own Typos.

[19] Arriving while the Lateran Synod was sitting, he realised how opposed the west was to the emperor's policy and set up Italy as an independent state; his army joined his rebellion.

[20] Constans appointed a new Exarch, Theodore I Calliopas, who marched on Rome with the newly loyal army, abducted Pope Martin and brought him to Constantinople where he was tried for high treason before the Senate; he was banished to Chersonesus (present-day Crimea)[21] and shortly after died as a result of his mistreatment.

[23] Constans viewed settling the dispute as a matter of state security, and persecuted anyone who spoke out against Monotheletism, including Maximus the Confessor and a number of his disciples.

Constans even personally journeyed to Rome in 663 to meet with the Pope, the first emperor to visit since the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Pope Vitalian, who had hosted the visit of Constans II to Rome in 663, almost immediately declared himself in favour of the doctrine of the two wills of Christ, the orthodox Chalcedonian position.