Tyrian purple

Production of Tyrian purple for use as a fabric dye began as early as 1200 BC by the Phoenicians, and was continued by the Greeks and Romans until 1453 AD, with the fall of Constantinople.

Like any perishable organic material, they are usually subject to rapid decomposition and their preservation over millennia requires exacting conditions to prevent destruction by microorganisms.

The even more sumptuous toga picta, solid Tyrian purple with gold thread edging, was worn by generals celebrating a Roman triumph.

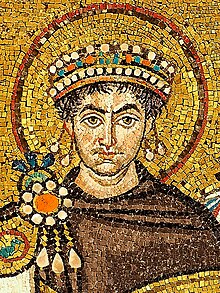

[4] By the fourth century AD, sumptuary laws in Rome had been tightened so much that only the Roman emperor was permitted to wear Tyrian purple.

Another dye extracted from a related sea snail, Hexaplex trunculus, produced a blue colour after light exposure which could be the one known as tekhelet (תְּכֵלֶת), used in garments worn for ritual purposes.

David Jacoby remarks that "twelve thousand snails of Murex brandaris yield no more than 1.4 g of pure dye, enough to colour only the trim of a single garment.

[21] This second species of dye murex is found today on the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts of Europe and Africa (Spain, Portugal, Morocco).

[24] Pliny the Elder described the production of Tyrian purple in his Natural History:[25][b] The most favourable season for taking these [shellfish] is after the rising of the Dog-star, or else before spring; for when they have once discharged their waxy secretion, their juices have no consistency: this, however, is a fact unknown in the dyers' workshops, although it is a point of primary importance.

About the tenth day, generally, the whole contents of the cauldron are in a liquefied state, upon which a fleece, from which the grease has been cleansed, is plunged into it by way of making trial; but until such time as the colour is found to satisfy the wishes of those preparing it, the liquor is still kept on the boil.

According to John Malalas, the incident happened during the reign of the legendary King Phoenix of Tyre, the eponymous progenitor of the Phoenicians, and therefore he was the first ruler to wear Tyrian purple and legislate on its use.

[29] Recently, the archaeological discovery of substantial numbers of Murex shells on Crete suggests that the Minoans may have pioneered the extraction of Imperial purple centuries before the Tyrians.

[30][31] Accumulations of crushed murex shells from a hut at the site of Coppa Nevigata in southern Italy may indicate production of purple dye there from at least the 18th century BC.

Evidence of the use of dye in pottery are found in most cases on the upper part of ceramic basins, on the inside surface, the areas in which the reduced dye-solution was exposed to air, and underwent oxidation that turned it purple.

[2] The production of Murex purple for the Byzantine court came to an abrupt end with the sack of Constantinople in 1204, the critical episode of the Fourth Crusade.

"[33] By contrast, Jacoby finds that there are no mentions of purple fishing or dyeing, nor trade in the colorant in any Western source, even in the Frankish Levant.

Not only did the people of ancient Mexico use the same methods of production as the Phoenicians, they also valued murex-dyed cloth above all others, as it appeared in codices as the attire of nobility.

"Nuttall noted that the Mexican murex-dyed cloth bore a "disagreeable ... strong fishy smell, which appears to be as lasting as the color itself.

[39] The final shade of purple is decided by chromatogram, which can be identified by high performance liquid chromatography analysis in a single measurement: indigotin (IND) and indirubin (INR).

The good semiconducting properties of the dye originate from strong intermolecular hydrogen bonding that reinforces pi stacking necessary for transport.

Ancient reports are also not entirely consistent, but these swatches give a rough indication of the likely range in which it appeared: _________ _________ The lower one is the sRGB colour #990024, intended for viewing on an output device with a gamma of 2.2.

The colour name "Tyrian plum" is popularly given to a British postage stamp that was prepared, but never released to the public, shortly before the death of King Edward VII in 1910.