Postage stamps and postal history of the United States

[5] In the years leading up to the American Revolution, mail routes among the colonies existed along the few roads between Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Montreal, Trois Rivieres, and Quebec City.

[10][11] Postage stamps revolutionized this process, leading to universal prepayment; but a precondition for their issue by a nation was the establishment of standardized rates for delivery throughout the country.

Greig, retained by the Post Office to run the service, kept the firm's original Washington stamp in use, but soon had its lettering altered to reflect the name change.

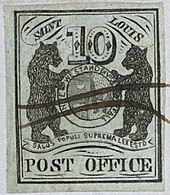

[16] However, Congress did not authorize the production of stamps for nationwide use until 1847; still, postmasters realized that standard rates now made it feasible to produce and sell "provisional" issues for prepayment of uniform postal fees, and printed these in bulk.

Congress finally provided for the issuance of stamps by passing an act on March 3, 1847, and the Postmaster-General immediately let a contract to the New York City engraving firm of Rawdon, Wright, Hatch, and Edson.

The post office had become so efficient by 1851 that Congress was able to reduce the common rate to three cents (which remained unchanged for over thirty years), necessitating a new issue of stamps.

[21] In February 1861, a congressional act directed that "cards, blank or printed ... shall also be deemed mailable matter, and charged with postage at the rate of one cent an ounce."

Raised lettering on the metal backs of the jackets often advertised the goods or services of business firms; these included the Aerated Bread Company; Ayer's Sarsaparilla and Cathartic Pills; Burnett's Cocoaine; Sands Ale; Drake's Plantation Bitters; Buhl & Co.

[27] The Post Office eventually adopted the grill, a device consisting of a pattern of tiny pyramidal bumps that would emboss the stamp, breaking up the fibers so that the ink would soak in more deeply, and thus be difficult to clean off.

Study of the stamps shows that there were eleven types of grill in use, distinguished by size and shape (philatelists have labeled them with letters A-J and Z), and that the practice started sometime in 1867 and was gradually abandoned after 1871.

These came out in 1869, and were notable for the variety of their subjects; the 2¢ depicted a Pony Express rider, the 3¢ a locomotive, the 12¢ the steamship Adriatic, the 15¢ the landing of Christopher Columbus, and the 24¢ the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

But the large banknotes did not represent a total retreat to past practices, for the range of celebrated Americans was widened beyond Franklin and various presidents to include notables such as Henry Clay and Oliver Hazard Perry.

One side was printed with a Liberty-head one-cent stamp design, along with the words "United States Postal Card" and three blank lines provided for the mailing address.

The Post Office got in on the act, issuing a series of 16 stamps depicting Columbus and episodes in his career, ranging in value from 1¢ to $5 (a princely sum in those days).

[21] The final issue of 1898 altered the colors of many denominations to bring the series into conformity with the recommendations of the Universal Postal Union (an international body charged with facilitating the course of transnational mail).

The result, paradoxically, was a substantial increase in Post Office profits; for, while the higher valued Columbians and Trans-Mississippis had sold only about 20,000 copies apiece, the public bought well over five million of every Pan-American denomination.

Although there were only two central images, a profile of Washington and one of Franklin, many subtle variants appeared over the years; for the Post Office experimented with half-a-dozen different perforation sizes, two kinds of watermarking, three printing methods, and large numbers of values, all adding to several hundred distinct types identified by collectors.

The eight lowest values illustrated aspects of mail handling and delivery, while higher denominations depicted such industries as Manufacturing, Dairying and Fruit Growing.

[citation needed] During this period, the U.S. Post Office issued more than a dozen 'Two Cent Reds' commemorating the 150th anniversaries of Battles and Events that occurred during the American Revolution.

(In a memorable sequence from Philip Roth's novel The Plot Against America, the young protagonist dreams that his National Parks stamps, the pride, and joy of his collection, have become disfigured with swastika overprints.)

Around 1935, Postmaster Farley removed sheets of the National Parks set from stock before they had been gummed or perforated, giving these and unfinished examples of ten other issues to President Roosevelt and Interior Secretary Harold Ickes (also a philatelist) as curiosities for their collections.

[46] The thirteen stamps present full color images of the national flags of Poland, Czechoslovakia, Norway, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Greece, Yugoslavia, Albania, Austria, Denmark, and Korea, with the names of the respective countries written beneath.

The other stamps in the series included liberty-related statesmen and landmarks, such as Patrick Henry and Bunker Hill, although other subjects, (Benjamin Harrison, for example) seem unrelated to the basic theme.

The Post Office had long avoided this image, fearing accusations that, in issuing stamps on which they would be defacing the flag by cancellation marks, they would be both committing and fomenting desecration.

Self-adhesives were not issued again until 1989, gradually becoming so popular that as of 2004[update], only a handful of types are offered with the traditional gum (now affectionately called "manual stamps" by postal employees).

[citation needed] The first US postage stamp to incorporate microprinting as a security feature was the American Wildflower Series introduced by the United States Postal Service in 1992.

[65] In 2006 sculptor Frank Gaylord enlisted Fish & Richardson to make a pro bono claim that the Postal Service had violated his Intellectual property rights to the sculpture and thus should have been compensated.

The Postal Service argued that Gaylord was not the sole sculptor (saying he had received advice from federal sources—who recommended that the uniforms appear more in the wind) and also that the sculpture was actually architecture.

In September 2011, however, the postal service announced that, in an attempt to increase flagging revenues, stamps would soon offer images of celebrated living persons, chosen by the Committee in response to suggestions submitted by the public via surface mail and social networks on the Internet.

The revised criterion reads: "The Postal Service will honor living men and women who have made extraordinary contributions to American society and culture.

issued in 1895

Issue of 1861

1870 issue

issue of 1912

issue of 1917

issue of 1915

issue of 1918