U Dhammaloka

Drawing on Western atheist writings, he publicly challenged the role of Christian missionaries, and resisted attempts by the colonial government to charge him for sedition.

Leaving the ship in Japan, he made his way to Rangoon, arriving probably in the late 1870s or early 1880s, before the Third Anglo-Burmese War, which marked the final conquest of Burma by the British.

Ocha before establishing his own mission and free school on Havelock Road in 1903, supported mainly by the Chinese community and a prominent local Sri Lankan jeweller.

Dhammaloka's presence at an October 'student conference' at the same university in company with the elderly Irish-Australian Theosophist Letitia Jephson is also described by American author Gertrude Adams Fisher in her 1906 travel book A Woman Alone in the Heart of Japan.

[25] Dhammaloka produced a large amount of published material, some of which, as was common for the day, consisted of reprints or edited versions of writing by other authors, mostly Western atheists or freethinkers, some of whom returned the favour in kind.

It was originally intended to produce ten thousand copies of each of a hundred tracts; while it is not clear if it reached this number of titles, print runs were very large.

[27] To date copies or indications have been found of at least nine different titles, including Thomas Paine's Rights of Man and Age of Reason, Sophia Egoroff's Buddhism: the highest religion, George W Brown's The teachings of Jesus not adapted to modern civilisation, William E Coleman's The Bible God disproved by nature, and a summary of Robert Blatchford.

[30] He was also a frequent topic of comment by the local press in South and Southeast Asia, by missionary and atheist authors, and by travel writers such as Harry Franck (1910).

[32][33] As a Buddhist preacher he seems to have deferred to Burmese monks for their superior knowledge of Buddhism and instead spoken primarily of the threat of missionaries, whom he identified as coming with "a bottle of 'Guiding Star brandy', a 'Holy bible' or 'Gatling gun'," linking alcoholism, Christianity and the British Army.

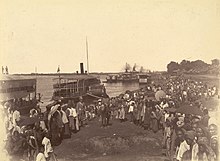

In Burma he received support from traditionalists (he was granted a meeting with the Thathanabaing, was treated with respect among senior Burmese monks and a dinner was sponsored in his honour), from rural Burmese (who attended his preaching in large numbers, sometimes travelling several days to hear him; in at least one case women laid down their hair for him to walk on as a gesture of great respect) and from urban nationalists (who organised his preaching tours, defended him in court etc.

Turner[37][38] speculates that this was to avoid the potential political embarrassment to the colonial authorities of trials with more substantial charges and hence a greater burden of proof.

During the shoe affair in 1902 it was alleged that Dhammaloka had said "we [the West] had first of all taken Burma from the Burmans and now we desired to trample on their religion" – an inflammatory statement taken as hostile to the colonial government and to Christianity.

Witnesses testified that he had described missionaries as carrying the Bible, whiskey and weapons, and accused Christians of being immoral, violent and set on the destruction of Burmese tradition.

Rather than a full sedition charge, the crown opted to prosecute through a lesser aspect of the law (section 108b) geared to the prevention of future seditious speech, which required a lower burden of proof and entailed a summary hearing.

[43][25] No reliable record of his death has been found, but it would not necessarily have been reported during the First World War, if it had taken place while he was travelling, or indeed if he had been given a traditional monastic funeral in a country such as Siam or Cambodia.

[46] These accounts do not mention Dhammaloka,[47] but construct a genealogy starting with Bhikkhus Asoka (H. Gordon Douglas), Ananda Metteyya (Allan Bennett) and Nyanatiloka (Anton Gueth).

[48] By contrast with Dhammaloka, Ananda Metteyya was oriented toward the image of gentleman scholar, avoided conflict with Christianity and aimed at making Western converts rather than supporting Burmese and other Asian Buddhists.

On the Burmese side, Dhammaloka takes up an intermediate place between traditionalist orientations towards simple restoration of the monarchy and the more straightforward nationalism of the later independence movement.