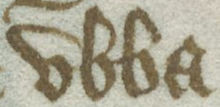

Ubba

Whilst there is reason to suspect that Edmund's cult was partly promoted to integrate Scandinavian settlers in Anglo-Saxon England, the legend of Ragnar Lodbrok may have originated in attempts to explain why they came to settle.

After the fall of the East Anglian kingdom, leadership of the Great Army appears to have fallen to Bagsecg and Halfdan, who campaigned against the Mercians and West Saxons.

Archaeological evidence and documentary sources suggest that this Great Army was not a single unified force, but more of a composite collection of warbands drawn from different regions.

[18] The Great Army may have included Vikings already active in Anglo-Saxon England, as well as men directly from Scandinavia, Ireland, the Irish Sea region and the Continent.

The considerable time that members of the Great Army appear to have spent in Ireland and on the Continent suggests that these men were well accustomed to Christian society, which in turn may partly explain their successes in Anglo-Saxon England.

[47][note 4] Also that year, Annales Bertiniani reports that Charles II, King of West Francia (died 877) paid off a Viking fleet stationed on the Seine.

This statement seems to suggest that these Vikings had intended to acquire a grant of lands in the region, which could mean that they thereafter took part in the Great Army's campaigning across the Channel.

[58] With the collapse of the Northumbrian kingdom, and the destruction of its regime, the 12th-century Historia regum Anglorum,[59] and Libellus de exordio, reveal that a certain Ecgberht (died 873) was installed by the Vikings as client king over a northern region of Northumbria.

[62][63] It was probably on account of this seemingly purchased peace that the Great Army relocated to York, as reported by the chronicle, where it evidently renewed its strength for future forays.

[64] The earliest source to make specific note of Ubba is Passio sancti Eadmundi, which includes him in its account of the downfall of Edmund, King of East Anglia (died 869).

[93][note 9] The apparent contradictory accounts of Edmund's demise given by these sources may stem from the telescoping of events surrounding an East Anglian military defeat and the subsequent capture and execution of the king.

Husband and wife lay dead or dying together on their thresholds; the babe snatched from its mother's breast was, in order to multiply the cries of grief, slaughtered before her eyes.

An impious soldiery scoured the town in fury, athirst for every crime by which pleasure could be given to the tyrant who from sheer love of cruelty had given orders for the massacre of the innocent.

[119][note 14] In contrast to Passio sancti Eadmundi, the 12th-century "F" version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle specifically identifies Ubba and Ivar as the chiefs of the men who killed the king.

[137] Although Passio sancti Eadmundi presents the invasion of East Anglia by Ubba and Ivar as a campaign of wanton rape and murder, the account does not depict the destruction of the kingdom's monasteries.

[162] The account of the burning given by Historia ecclesiastica may well be the inspiration behind the tale of facial mutilation and fiery martyrdom first associated with Coldingham by the Wendover version of Flores historiarum.

[209] The account of events presented by Passio sancti Eadmundi seems to show that Edmund was killed in the context of the Great Army attempting to impose authority over him and his realm.

Although Alfred, King of Wessex (died 899) sued for peace in 876, the Vikings broke the truce the following year, seized Exeter, and were finally forced to withdraw back to Mercia.

[245][note 28] Vita Alfredi specifies that it was fought at a fortress called Arx Cynuit,[247] a name which appears to equate to what is today Countisbury, in North Devon.

[260][note 31] Although Ubba is identified as the slain commander by the 12th-century Estoire des Engleis,[262] it is unknown whether this identification is merely an inference by its author, or if it is derived from an earlier source.

[263] In any case, Estoire des Engleis further specifies that Ubba was slain at "bois de Pene"[266]—which may refer to Penselwood, near the Somerset–Wiltshire border[267]—and buried in Devon within a mound called "Ubbelawe".

[281] Whilst Vita Alfredi attributes the outcome to unnamed thegns of Alfred,[282] Chronicon Æthelweardi identifies the victorious commander as Odda, Ealdorman of Devon (fl.

As such, there is reason to suspect that the two Viking armies coordinated their efforts in an attempt to corner Alfred in a pincer movement after his defeat at Chippenham and subsequent withdrawal into the wetlands of Somerset.

[301] Although Alfred's position may have been still perilous in the aftermath, with his contracted kingdom close to collapse,[237] the victory at Arx Cynuit certainly foreshadowed a turn of events for the West Saxons.

[372][note 43] Although this text is heavily dependent upon Passio sancti Eadmundi for its depiction of Edmund's death, it appears to be the first source to meld the martyrdom with the legend of Ragnar Lodbrok.

[401] For example, the Wendover account states that Lodbrok (Lothbrocus) washed ashore in East Anglia, where he was honourably received by Edmund, but afterwards murdered by Björn (Berno), an envious huntsman.

[402][note 46] A slightly different version of events is offered by Estoire des Engleis, which states that the Vikings invaded Northumbria on behalf of Björn (Buern Bucecarle), who sought vengeance for the rape of his wife by the Northumbrian king, Osberht.

[410][note 48] On the other hand, the revenge motifs and miraculous maritime journeys presented in the accounts of Edmund are well-known elements commonly found in contemporaneous chivalric romances.

[415][note 49] The shared kinship assigned to Ivar and Ubba within the legend of Ragnar Lodbrok may stem from their combined part in Edmund's downfall as opposed to any historical familial connection.

[454] Ubba, Halfdan and Ivar the Boneless appear in the Ubisoft video game Assassin's Creed Valhalla as brothers, sharing significant roles in the story of Viking conquests of England during the 9th century.