Soil consolidation

The theoretical framework of consolidation is therefore closely related to the concept of effective stress, and hydraulic conductivity.

The early theoretical modern models were proposed one century ago, according to two different approaches, by Karl Terzaghi and Paul Fillunger.

The Terzaghi’s model is currently the most utilized in engineering practice and is based on the diffusion equation.

[1] In the narrow sense, "consolidation" refers strictly to this delayed volumetric response to pressure change due to gradual movement of water.

This broader definition encompasses the overall concept of soil compaction, subsidence, and heave.

Some types of soil, mainly those rich in organic matter, show significant creep, whereby the soil changes volume slowly at constant effective stress over a longer time-scale than consolidation due to the diffusion of water.

Coarse-grained soils do not undergo consolidation settlement due to relatively high hydraulic conductivity compared to clays.

The first modern theoretical models for soil consolidation were proposed in the 1920s by Terzaghi and Fillunger, according to two substantially different approaches.

[1] The former was based on diffusion equations in eulerian notation, whereas the latter considered the local Newton’s law for both liquid and solid phases, in which main variables, such as partial pressure, porosity, local velocity etc., were involved by means of the mixture theory.

Terzaghi had an engineering approach to the problem of soil consolidation and provided simplified models that are still widely used in engineering practice today, whereas, on the other hand, Fillunger had a rigorous approach to the above problems and provided rigorous mathematical models that paid particular attention to the methods of local averaging of the involved variables.

Fillunger’s model was very abstract and involved variables that were difficult to detect experimentally, and, therefore, it was not applicable to the study of real cases by engineers and/or designers.

Due to the different approach to the problem of consolidation by the two scientists, a bitter scientific dispute arose between them, and this unfortunately led to a tragic ending in 1937.

After Fillunger’s suicide, his theoretical results were forgotten for decades, whereas the methods proposed by Terzaghi found widespread diffusion among scientists and professionals.

In the following decades Biot fully developed the three-dimensional soil consolidation theory, extending the one-dimensional model previously proposed by Terzaghi to more general hypotheses and introducing the set of basic equations of poroelasticity.

Today, the Terzaghis’ one dimensional model is still the most utilized by engineers for its conceptual simplicity and because it is based on experimental data, such as oedometer tests, which are relatively simple, reliable and inexpensive and for which theoretical solutions in closed form are well known.

[2] Consolidation is the process in which reduction in volume takes place by the gradual expulsion or absorption of water under long-term static loads.

A soil that is currently experiencing its highest stress is said to be "normally consolidated" and has an OCR of one.

A soil could be considered "underconsolidated" or "unconsolidated" immediately after a new load is applied but before the excess pore water pressure has dissipated.

Occasionally, soil strata form by natural deposition in rivers and seas may exist in an exceptionally low density that is impossible to achieve in an oedometer[clarification needed]; this process is known as "intrinsic consolidation".

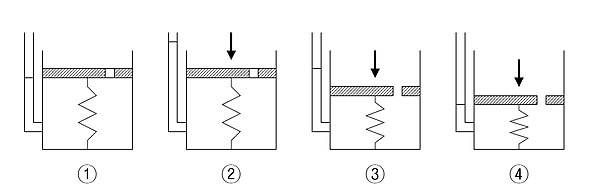

[6] The process of consolidation is often explained with an idealized system composed of a spring, a container with a hole in its cover, and water.

This is especially true in saturated clays because their hydraulic conductivity is extremely low, and this causes the water to take an exceptionally long time to drain out of the soil.

While drainage is occurring, the pore water pressure is greater than normal because it is carrying part of the applied stress (as opposed to the soil particles).

where Tv is the time factor; Hdr is the average longest drain path during consolidation; t is the time at measurement; Cv is defined as the coefficient of consolidation found using the log method with

The theoretical formulation above assumes that time-dependent volume change of a soil unit only depends on changes in effective stress due to the gradual restoration of steady-state pore water pressure.

This is the case for most types of sand and clay with low amounts of organic material.

Soil creep is typically caused by viscous behavior of the clay-water system and compression of organic matter.

This process of creep is sometimes known as "secondary consolidation" or "secondary compression" because it also involves gradual change of soil volume in response to an application of load; the designation "secondary" distinguishes it from "primary consolidation", which refers to volume change due to dissipation of excess pore water pressure.

Analytically, the rate of creep is assumed to decay exponentially with time since application of load, giving the formula:

The compressibility of saturated specimens of clay minerals increases in the order kaolinite < illite < smectite[clarification needed].

The compression index Cc, which is defined as the change in void ratio per 10-fold increase in consolidation pressure, is in the range of 0.19 to 0.28 for kaolinite, 0.50 to 1.10 for illite, and 1.0 to 2.6 for montmorillonite, for different ionic forms.