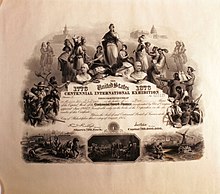

Centennial Exposition

It was the first official world's fair to be held in the United States and coincided with the centennial anniversary of the Declaration of Independence's adoption in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776.

Both had a similar neo-Gothic appearance, including the waving flags, a huge central hall, the "curiosities" and relics, handmade and industrial exhibits, and also a visit from the U.S. president and his family.

The idea of the Centennial Exposition is credited to John L. Campbell, a professor of mathematics, natural philosophy, and astronomy at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana.

[citation needed] The Philadelphia City Council and the Pennsylvania General Assembly created a committee to study the project and seek support of the U.S. Congress.

(And in fact, after the exposition ended, the federal government sued to have the money returned, and the United States Supreme Court ultimately forced repayment.)

The Commission decided to classify the exhibits into seven departments: agriculture, art, education and science, horticulture, machinery, manufactures, and mining and metallurgy.

Newspaper publisher John W. Forney agreed to head and pay for a Philadelphia commission sent to Europe to invite nations to exhibit at the exposition.

A small hospital was built on the exposition's grounds by the Centennial's Medical Bureau, but despite a heat wave during the summer, no mass health crises occurred.

Drawing lessons from this failure, the Philadelphia exposition was ready for its visitors, with direct railroad connections to service passenger trains every 30 minutes, trolley lines, street cars, carriage routes, and even docking facilities on the river.

The Centennial Commission turned to third-place winner's architect Henry Pettit and engineer Joseph M. Wilson for design and construction of the Main Exhibition Building.

[19] Situated high atop a hill presiding over Fountain Avenue, Horticultural Hall epitomized floral achievement, which attracted professional and amateur gardeners.

In dramatic fashion, the exposition introduced the general public to the notion of landscape design, as exemplified the building itself and the grounds surrounding it.

A long, sunken parterre leading to Horticultural Hall became the exposition's iconic floral feature, reproduced on countless postcards and other memorabilia.

Designed by Joseph M. Wilson and Henry Pettit, Machinery Hall was the second largest structure in the exposition and located west of the Main Exhibition Building.

The 1,400 horsepower engine was 45 ft (14 m) tall, weighed 650 tons, and had 1 mi (1.6 km) of overhead line belts connecting to the machinery in the building.

[22] Memorial Hall was designed by Herman J. Schwarzmann, who basically adopted an art museum plan submitted by Nicholas Félix Escalier to the Prix de Rome competition in 1867–69.

Female organizers drew upon deep-rooted traditions of separatism and sorority in planning, fundraising, and managing a pavilion devoted entirely to the artistic and industrial pursuits of their gender.

Elizabeth Duane Gillespie, president of the Women's Centennial Committee, led the effort to gather 82,000 signatures in two days to raise money for the pavilion.

On exhibit were over 80 patented inventions, including a reliance stove, a hand attachment for sewing machines, a dishwasher, a fountain griddle-greaser, a heating iron with removable handle, a frame for stretching and drying lace curtains, and a stocking and glove darner.

Exhibits demonstrated positive achievements and women's influence in domains such as industrial and fine arts (wood-carvings, furniture-making, and ceramics), fancy articles (clothing and woven goods), and philanthropy as well as philosophy, science, medicine, education, and literature.

[26] Eleven nations had their own exhibition buildings, and others contributed small structures, including the Swedish School house referenced below, now in Central Park, New York City.

[31] The formal name of the exposition was the International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures, and Products of the Soil and Mine, but the official theme was the celebration of the United States centennial.

[1] The exposition was originally scheduled to open in April, marking the anniversary of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, but construction delays caused the date to be pushed back to May 10.

[32] The opening ceremony concluded in Machinery Hall, with Grant and Pedro II turning on the Corliss Steam Engine which powered most of the other machines at the exposition.

[33] Cooling temperatures, news reports, and word of mouth began increasing attendance in the final three months of the exposition, with many of the visitors coming from farther distances.

Inventions included the typewriter and electric pen along with new types of mass-produced sewing machines, stoves, lanterns, guns, wagons, carriages, and agricultural equipment.

The exposition also featured many well-known products including Alexander Graham Bell's first telephone, set up at opposite ends of Machinery Hall, Thomas Edison's automatic telegraph system, screw-cutting machines that dramatically improved the production of screws and bolts from 8,000 to 100,000 per day, and a universal grinding machine by the Brown & Sharpe Manufacturing Company.

Its showpiece was the Gothic Revival high altar that Edward Sorin, founder of University of Notre Dame, had commissioned from the workshop of Désiré Froc-Robert & Sons in Paris.

Featuring costumed presenters and a "colonial kitchen" complete with a spinning wheel, the reconstructed mansion was accompanied by a polemical narrative about "old-fashioned domesticity".

Beaver Falls Cutlery Company exhibited the "largest knife and fork in the world" made by Chinese immigrant workers, among others.