2020 United States redistricting cycle

[citation needed] Prior to the 2022 U.S. House elections, each state apportioned more than one representative will draw new congressional districts based on the reapportionment following the 2020 census.

[12] The legislatures of Alabama, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia can override gubernatorial vetoes with a simple majority vote,[13] giving governors in those states little leverage in the drawing of new district maps.

[15] The Voting Rights Act of 1965 establishes protections against racial redistricting plans that would deny minority voters an equal opportunity to elect representatives of their choice.

The Supreme Court case of Thornburg v. Gingles established a test to determine whether redistricting lines violate the Voting Rights Act.

[16] In addition to standards required by federal law, many states have also adopted other criteria, including compactness, contiguity, and the preservation of political subdivisions (such as cities or counties) or communities of interest.

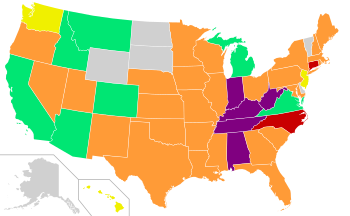

[17] The table shows the partisan control of states in which congressional redistricting is enacted through either a bill or a joint resolution passed by the legislature.

"*" indicates that a 2/3 super-majority vote is required in the legislature "↑" indicates that one party can override a gubernatorial veto because of a supermajority in the legislature "†" indicates that the state employs an advisory commission "‡" indicates that the state employs a back-up commission Ohio requires certain qualified majorities, at each stage of its congressional redistricting process, for its congressional maps to endure (subject to judicial review) for the full decade.

[22] Ohio employs a hybrid commission as a back-up redistricting authority in the case of the state legislature failing to achieve a certain qualified majority for approval of a map.

[23] The legislatures of Alabama, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia can override gubernatorial vetoes with a simple majority vote,[13] giving governors in those states little leverage in the drawing of new district maps.

[24] The Voting Rights Act of 1965 establishes protections against racial redistricting plans that would deny minority voters an equal opportunity to elect representatives of their choice.

The Supreme Court case of Thornburg v. Gingles established a test to determine whether redistricting lines violate the Voting Rights Act.

[16] Many states have also adopted other criteria, including compactness, contiguity, and the preservation of political subdivisions (such as cities or counties) or communities of interest.

In Missouri, a commission is created for each legislative chamber as a result of the governor picking from lists submitted by the leaders of the two major parties.

As more states continue to adopt maps through the redistricting process, the number of lawsuits filed will potentially increase.

[103] On January 24, 2022, a three-judge panel blocked Alabama's congressional maps over claims it likely violates the VRA.

The panel argued that because African Americans counted for a considerable percentage of the total population growth, there should be more opportunities for representation.

[109] A Trump appointed US District judge ruled that the groups did not have standing, and stated that the plaintiff must be the US Attorney General in February, 2022.

[111] US Senator Tom Cotton filed an amicus brief with the court supporting the state of Arkansas, calling racial gerrymandering accusations "baseless".

[116] Later, in October 2023, Judge Jones found that Georgia's maps did illegally discriminate against Black voters, ordering the state to create an additional majority-Black district.

[123] In December 2021, the Department of Justice also filed a lawsuit against Texas's new congressional and state house maps, arguing that they "were drawn with discriminatory intent".

[127] On March 25, a circuit court judge threw out the congressional districts, calling them an "extreme gerrymander" that disenfranchised multiple communities of interest.

[130] Federal Judge Gary L. Sharpe of the Northern District of New York delayed New York's congressional and state senate primaries to August in May 2022, rejecting an argument from state Democrats that the primary must take place in June, and so it was too late to redraw new maps.

He called the argument "a Hail Mary pass, the object of which is to take a long-shot try at having the New York primaries conducted on district lines that the state says is unconstitutional".

New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham characterized the congressional map as one "in which no one party or candidate may claim any undue advantage.

[citation needed] The Connecticut Supreme Court was forced to take over the congressional redistricting process after the bipartisan legislative panel deadlocked and failed to agree on new maps.

The court appointed Nathaniel Persily, who drew Connecticut's 2010 maps, as special master to draw the new congressional districts.

[137] Persily drew a least-change map, making only the adjustments necessary to ensure equal population in each congressional district.

[43] North Carolina House Speaker Tim Moore called the process "egregious" and "unconstitutional", and accused the court of drawing the maps "in an unknown, black-box manner".

[146] The formula had covered states with a history of minority voter disenfranchisement, and the preclearance procedure was designed to block discriminatory voting practices.

[147] In another 2019 case, Department of Commerce v. New York, the Supreme Court blocked the Trump administration from adding a question to the 2020 census regarding the citizenship of respondents.

- ^ Louisiana is labeled as Republican because the Democratic governor vetoed the maps but was overridden with almost no Democratic votes

- ^ Maryland is labeled as bipartisan because the Republican governor signed the Democratic-controlled legislature's maps after a court overturned a Democratic gerrymander as a deal to drop the legislature's appeal