University of al-Qarawiyyin

[12][13] Education at the University of al-Qarawiyyin concentrates on the Islamic religious and legal sciences with a heavy emphasis on, and particular strengths in, Classical Arabic grammar/linguistics and Maliki Sharia, though lessons on non-Islamic subjects are also offered to students.

[14] Deverdun suggested the inscription may have come from another unidentified mosque and was moved here at a later period (probably 15th or 16th century) when the veneration of the Idrisids was resurgent in Fez, and such relics would have held enough religious significance to be reused in this way.

[26]: 287 [1]: 71 [27] Major mosques in the early Islamic period were typically multi-functional buildings where teaching and education took place alongside other religious and civic activities.

[21]: 453 It is unclear at what time al-Qarawiyyin began to act more formally as an educational institution, partly because of the limited historical sources that pertain to its early period.

[40] Part of the collection was gathered decades earlier by Sultan Abu Yusuf Ya'qub (ruled 1258–1286), who persuaded Sancho IV of Castile to hand over a number of works from the libraries of Seville, Córdoba, Almeria, Granada, and Malaga in al-Andalus/Spain.

[40] Students were male, but traditionally it has been said that "facilities were at times provided for interested women to listen to the discourse while accommodated in a special gallery (riwaq) overlooking the scholars' circle".

[26] The 12th-century cartographer Mohammed al-Idrisi, whose maps aided European exploration during the Renaissance, is said to have lived in Fez for some time, suggesting that he may have worked or studied at al-Qarawiyyin.

[1][30] In 1788–89, the 'Alawi sultan Muhammad ibn Abdallah introduced reforms that regulated the institution's program, but also imposed stricter limits and excluded logic, philosophy, and the more radical Sufi texts from the curriculum.

[24] At the time Morocco became a French protectorate in 1912, al-Qarawiyyin worsened as a religious center of learning from its medieval prime,[1] though it retained some significance as an educational venue for the sultan's administration.

[51]: 140, 146 In July 1930, al-Qarawiyyin strongly participated in the propagation of Ya Latif, a communal prayer recited in times of calamity, to raise awareness and opposition to the Berber Dahir decreed by the French authorities two months earlier.

[55] In 1988, after a hiatus of almost three decades, the teaching of traditional Islamic education at al-Qarawiyyin was resumed by King Hassan II in what has been interpreted as a move to bolster conservative support for the monarchy.

[1] Education at al-Qarawiyyin University concentrates on the Islamic religious and legal sciences with a heavy emphasis on, and particular strengths in, Classical Arabic grammar/linguistics and Maliki law, though some lessons on other non-Islamic subjects such as French and English are also offered to students.

[c] In addition to being Muslim, prospective students of al-Qarawiyyin are required to have fully memorized the Quran, as well as other shorter medieval Islamic texts on grammar and Maliki law, and to be proficient in classical Arabic.

The Zenata Berber emir Ahmed ibn Abi Said, one of the rulers of Fez during this period who was aligned with the Umayyads, wrote to the caliph Abd al-Rahman III in Córdoba for permission and funds to expand the mosque.

[5]: 20 [60]: 193 This expansion required the purchase and demolition of a number of neighboring houses and structures, including some that were apparently part of the nearby Jewish neighbourhood (before the Mellah of Fez).

This involved not only embellishing some of the arches with new forms but also adding a series of highly elaborate cupola ceilings composed in muqarnas (honeycomb or stalactite-like) sculpting and further decorated with intricate reliefs of arabesques and Kufic letters.

[5][62] The craftsmen who worked on this expansion are mostly anonymous, except for two names that are carved on the bases of two of the cupolas: Ibrāhīm and Salāma ibn Mufarrij, who may have been of Andalusi origin.

[68][69] It was designed by Abu Zayd Abd al-Rahman ibn Sulayman al-Laja'i and completed on November 20, 1361 (21 Muharram 763 AH), as recorded by an original inscription.

[34] The gates vary from small rectangular doorways to enormous horseshoe arches with huge doors preceded by wooden roofs covering the street in front of them.

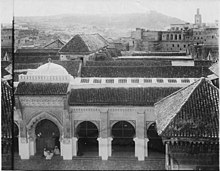

The main area, south of the courtyard, is a vast space divided into ten transverse aisles by rows of arches running parallel to the southern wall.

[20]: 119–120 Many of the muqarnas compositions are further embellished with intricate reliefs of arabesques and Arabic inscriptions in both Kufic and cursive letters, highlighted with blue and red colours.

Its entrance is covered by a wooden screen from the Marinid period which features an inscription carved in cursive Arabic above the doorway recording Abu Inan's foundation of the library.

[5]: 64 The current library building dates in part from a Saadian construction by Ahmad al-Mansur (late 16th century), who built a chamber called al-Ahmadiyya behind the qibla wall.

It included the current grand reading room, which measures 23 metres long and features an ornately-painted wooden ceiling, and also added an entrance outside the mosque which made it accessible to non-Muslims.

[11] Many scholars consider that the university was only adopted outside the West, including into the Islamic world, in the course of modernization programs or under European colonial regimes since the beginning of the 19th century.

[102][103][104] Other scholars have questioned this, citing the lack of evidence for an actual transmission from the Islamic world to Christian Europe and highlighting the differences in the structure, methodologies, procedures, curricula and legal status of the madrasa versus the European university.

by means of an endowment bequeathed by a wealthy woman of much piety, Fatima bint Muhammed al-Fahri.Higher education has always been an integral part of Morocco, going back to the ninth century when the Karaouine Mosque was established.

It is no doubt true that other civilizations, prior to, or wholly alien to, the medieval West, such as the Roman Empire, Byzantium, Islam, or China, were familiar with forms of higher education which a number of historians, for the sake of convenience, have sometimes described as universities.

Yet a closer look makes it plain that the institutional reality was altogether different and, no matter what has been said on the subject, there is no real link such as would justify us in associating them with medieval universities in the West.

The four medieval faculties of artes – variously called philosophy, letters, arts, arts and sciences, and humanities –, law, medicine, and theology have survived and have been supplemented by numerous disciplines, particularly the social sciences and technological studies, but they remain nonetheless at the heart of universities throughout the world.Even the name of the Universitas, which in the Middle Ages was applied to corporate bodies of the most diverse sorts and was accordingly applied to the corporate organization of teachers and students, has in the course of centuries been given a more particular focus: the university, as a universitas litterarum, has since the eighteenth century been the intellectual institution which cultivates and transmits the entire corpus of methodically studied intellectual disciplines.In many respects, if there is any institution that Europe can most justifiably claim as one of its inventions, it is the university.