Uralic languages

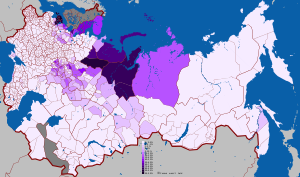

Other languages with speakers above 100,000 are Erzya, Moksha, Mari, Udmurt and Komi spoken in the European parts of the Russian Federation.

[7] Scholars who do not accept the traditional notion that Samoyedic split first from the rest of the Uralic family may treat the terms as synonymous.

Fogel's unpublished study of the relationship, commissioned by Cosimo III of Tuscany, was clearly the most modern of these: he established several grammatical and lexical parallels between Finnish and Hungarian as well as Sámi.

[19] Several early reports comparing Finnish or Hungarian with Mordvin, Mari or Khanty were additionally collected by Gottfried Leibniz and edited by his assistant Johann Georg von Eckhart.

Hungarian intellectuals especially were not interested in the theory and preferred to assume connections with Turkic tribes, an attitude characterized by Merritt Ruhlen as due to "the wild unfettered Romanticism of the epoch".

[24]Up to the beginning of the 19th century, knowledge of the Uralic languages spoken in Russia had remained restricted to scanty observations by travelers.

[25] One of the first of these was undertaken by Anders Johan Sjögren, who brought the Vepsians to general knowledge and elucidated in detail the relatedness of Finnish and Komi.

[26] Still more extensive were the field research expeditions made in the 1840s by Matthias Castrén (1813–1852) and Antal Reguly (1819–1858), who focused especially on the Samoyedic and the Ob-Ugric languages, respectively.

[27] Budenz was the first scholar to bring this result to popular consciousness in Hungary and to attempt a reconstruction of the Proto-Finno-Ugric grammar and lexicon.

[33] Meanwhile, in the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland, a chair for Finnish language and linguistics at the University of Helsinki was created in 1850, first held by Castrén.

[35] During the late 19th and early 20th century (until the separation of Finland from Russia following the Russian Revolution), the Society hired many scholars to survey the still less-known Uralic languages.

[36] The vast amounts of data collected on these expeditions would provide over a century's worth of editing work for later generations of Finnish Uralicists.

[43][57] A recent competing proposal instead unites Ugric and Samoyedic in an "East Uralic" group for which shared innovations can be noted.

[59] The term Volgaic (or Volga-Finnic) was used to denote a branch previously believed to include Mari, Mordvinic and a number of the extinct languages, but it is now obsolete[43] and considered a geographic classification rather than a linguistic one.

A recent re-evaluation of the evidence[54] however fails to find support for Finno-Ugric and Ugric, suggesting four lexically distinct branches (Finno-Permic, Hungarian, Ob-Ugric and Samoyedic).

One alternative proposal for a family tree, with emphasis on the development of numerals, is as follows:[12] Another proposed tree, more divergent from the standard, focusing on consonant isoglosses (which does not consider the position of the Samoyedic languages) is presented by Viitso (1997),[60] and refined in Viitso (2000):[61] The grouping of the four bottom-level branches remains to some degree open to interpretation, with competing models of Finno-Saamic vs. Eastern Finno-Ugric (Mari, Mordvinic, Permic-Ugric; *k > ɣ between vowels, degemination of stops) and Finno-Volgaic (Finno-Saamic, Mari, Mordvinic; *δʲ > *ð between vowels) vs. Permic-Ugric.

Extending this approach to cover the Samoyedic languages suggests affinity with Ugric, resulting in the aforementioned East Uralic grouping, as it also shares the same sibilant developments.

Structural characteristics generally said to be typical of Uralic languages include: Basic vocabulary of about 200 words, including body parts (e.g. eye, heart, head, foot, mouth), family members (e.g. father, mother-in-law), animals (e.g. viper, partridge, fish), nature objects (e.g. tree, stone, nest, water), basic verbs (e.g. live, fall, run, make, see, suck, go, die, swim, know), basic pronouns (e.g. who, what, we, you, I), numerals (e.g. two, five); derivatives increase the number of common words.

The following is a very brief selection of cognates in basic vocabulary across the Uralic family, which may serve to give an idea of the sound changes involved.

As is apparent from the list, Finnish is the most conservative of the Uralic languages presented here, with nearly half the words on the list above identical to their Proto-Uralic reconstructions and most of the remainder only having minor changes, such as the conflation of *ś into /s/, or widespread changes such as the loss of *x and alteration of *ï. Finnish has also preserved old Indo-European borrowings relatively unchanged.

(An example is porsas ("pig"), loaned from Proto-Indo-European *porḱos or pre-Proto-Indo-Iranian *porśos, unchanged since loaning save for loss of palatalization, *ś > s.) The Estonian philologist Mall Hellam proposed cognate sentences that she asserted to be mutually intelligible among the three most widely spoken Uralic languages: Finnish, Estonian, and Hungarian:[69] However, linguist Geoffrey Pullum reports that neither Finns nor Hungarians could understand the other language's version of the sentence.

[81] This hypothesis has, however, been rejected by some specialists in Uralic languages,[82] and has in recent times also been criticised by other Dravidian linguists, such as Bhadriraju Krishnamurti.