Urban planning in Singapore

The most recent plan is the 2019 masterplan, which details Singapore's increasing consideration towards sustainability, cultural preservation, building communities and closing resource loops.

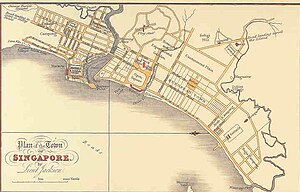

[3] To make Singapore a commercial and administrative centre, haphazardly constructed buildings were discouraged and significant disruptions were caused by the massive movements of people to and from their designated areas.

Furthermore, to add professionalism to the planning process, Raffles secured the services of G.P Coleman, an architect and surveyor, and appointed Jackson, an assistant engineer), to build and oversee the development of the island.

[5] The demarcations also allowed the British political and economic control over the separated indigenous population, depending on the European Quarter as an administrative and commercial centre.

[1] This observation was made with regards to Singapore in the 1920s: ... a striking example of a planless modern city and regional growth undirected by any comprehensive general plan and complementary schemes of improvement and development.

The outcome of their modern growth is much unnecessary disorder, congestion and difficulties for which remedial measures have long been overdue [sic][7] In 1918, in response to a Housing Committee's findings regarding unsanitary living conditions posing a health hazard,[1] the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) was established in 1927.

[9] In the years preceding the Second World War, the SIT concentrated mostly on building and improving roads and open spaces, and constructing public housing.

The plan was conceived with the expectation that Singapore would grow gradually and was unsuited for the social and economic change, rapid population growth and the Central Area's expansion in the early 1960s.

While the 1958 Master Plan provided a guide for the control of development and land use, it became inadequate for the rapidly changing social and economic conditions in Singapore as a result of self governance and time lapses between policy formulation and implementation.

The main problems that the plan had to target was the high rate of population growth, rapid expansion of central area, traffic congestion and deterioration of the city core.

Key developments in the city core include Shenton Way (Singapore's Wall Street) and Orchard Road (a shopping belt for tourists and higher-income Singaporeans).

Through 'active programs' which involved both public and private participation, URA revamped the road system and drastically changed the built environment of central Singapore.

[11] Led by its three guiding principles of conservation, rehabilitation, and rebuilding, URA planned and created a city that is physically, economically, and culturally regarded as a modern metropolis.

[14] The simultaneous development of mass housing and urban renewal also allowed large amounts of the population to be systematically transferred from the city core to the suburbs.

Since housing and urban renewal were at the top of the government's priorities, URA was given access to resources, capital, and manpower on a national scale for its development activities.

While Singapore's development focused mainly on economic success during the initial post-independence years, as Singaporeans became more affluent in the 1980s, planners started taking into account quality of life factors.

Additional land within new towns was allocated for parks and open spaces, while gardens and common facilities were incorporated into public housing estates to foster a sense of community between residents.

In line with the shift towards making Singapore more liveable, the revised Concept Plan touched on all aspects of life, from business to leisure, powered by economic growth.

Its main focuses include sustaining economic growth, increasing transport efficiency and providing comfortable accommodation for 4 million people and improving the quality of life for the population.

Urban development would be integrated with the natural environment, with an island-wide network of blue and green linkages and locating residential estates near waterfronts, parks and gardens.

Development of more resorts, marinas, beaches, sports facilities, entertainment complexes and theme parks were also planned to provide the population a wider range of leisure options.

The 2001 plan mainly focused on quality of life, proposing more diverse residential and recreational developments, and balancing the goals of liveability and economic growth.

[16] Green spaces would be expanded from 2000 to 4500 ha, with the opening of areas such as Pulau Ubin and the Central Catchment Reserve, which will be accessible by Park Connectors.

Three regional centres were also added to the mix, with Tampines, Jurong East and Woodlands supported by an expansive train network which provides links to places island-wide.

Consisting of members from many parts of society, it was intended to provide feedback on the URA's conservation proposals, and to encourage the public to learn more about Singapore's built heritage.

A Transit Priority Corridor is also in the works, where bus lanes and cyclists enjoy seamless journeys, encouraging residents to cycle or take public transport.

[27] The central area, home to Singapore's financial hub, will continue to grow, accommodating more nearby housing and a larger diversity of jobs in the future.

Beyond being an economic powerhouse, Singapore's planning priorities have expanded to sustainability, culture and resource preservation, bolstered by the use of advanced technology to create smarter cities.

[31] Over 90% of Singaporeans or Permanent Residents own their own home and at the 2010 Venice Architecture Biennale, it was calculated that with Singapore's land-use efficiency, the world's population could fit into 0.5% of the Earth's landmass.

In February 2021, a woodland reserve the size of 10 football fields just Northwest of Kranji was accidentally cleared for construction purposes, drawing intense criticism from Singapore's conservation groups.