Uruk period

This is the region of the Near East that was the most agriculturally productive, as a result of an irrigation system which developed in the 4th millennium BC and focused on the cultivation of barley (along with the date palm and various other fruits and legumes) and the pasturing of sheep for their wool.

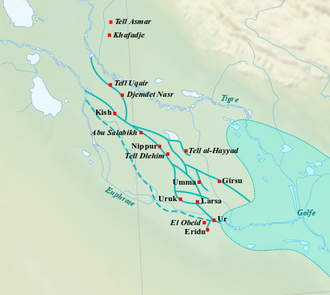

[13][28] The sources relating to the Uruk period derive from a group of sites distributed over an immense area, covering all of Mesopotamia and the neighboring regions up to central Iran and southeastern Anatolia.

But in other areas the Uruk culture is more evident, such as Upper Mesopotamia (Girdi Qala and Logardan, Grai Resh, Tell al-Hawa, and Kani Shaie for example), northern Syria, western Iran and southeastern Anatolia.

Level V of Godin Tepe could be interpreted as an establishment of merchants from Susa and/or lower Mesopotamia, interested in the location of the site on commercial routes, especially those linked to the tin and lapis lazuli mines on the Iranian Plateau and in Afghanistan.

The excavations there have revealed some very rich tombs, different kinds of residence, workshops, and very large buildings with an official or religious function (notably the 'round structure'), which may indicate that Tepe Gawra was a regional political centre.

The fact that the characteristics of the culture of the Uruk region are found across such a large territory (from northern Syria to the Iranian plateau), with Lower Mesopotamia as a clear centre, led the archaeologists who studied this period to see this phenomenon as an 'Uruk expansion'.

Or was it perhaps some sort of an infiltration by groups of Urukean or southern Mesopotamian people trying to farm suitable lands – perhaps even by some refugees fleeing growing political oppression and overcrowding at Uruk?

For Algaze, the motivation of this activity is considered to be a form of economic imperialism: the elites of southern Mesopotamia wanted to obtain the numerous raw materials which were not available in the Tigris and Euphrates floodplains, and founded their colonies on nodal points which controlled a vast commercial network (although it remains impossible to determine what exactly was exchanged), settling them with refugees as in some models of Greek colonisation.

However, although long-distance trade is undoubtedly a secondary phenomenon for the south Mesopotamian states compared to local production and seems to follow the development of increased social complexity rather than causing it, this does not necessarily prove a process of colonisation.

[57] Some other theories propose a form of agrarian colonisation resulting from a shortage of land in Lower Mesopotamia or a migration of refugees after the Uruk region suffered ecological or political upheavals.

[62][63] In Egypt, Urukian influence seems to be limited to a few objects which were seen as prestigious or exotic (most notably the knife of Jebel el-Arak), chosen by the elite at a moment when they needed to assert their power in a developing state.

This is especially the case in English-language scholarship, in which the theoretical approaches have been largely inspired by anthropology since the 1970s, and which has studied the Uruk period from the angle of 'complexity' in analysing the appearance of early states, an expanding social hierarchy, intensification of long-distance trade, etc.

A first group of developments took place in the field of cereal cultivation, followed by the invention of the ard—a wooden plough pulled by an animal (ass or ox)—towards the end of the 4th millennium BC, which enabled the production of long furrows in the earth.

The date of its first cultivation by man can't be precisely determined: it is commonly supposed that the culture of this tree knew its development during the Late Uruk period, but the texts are not explicit on this matter.

Beyond the expansion of sheep farming, these were notably in the institutional framework,[80] which led to changes in agricultural practice with the introduction of pasturage for these animals in the fields, as convertible husbandry, and in the hilly and mountainous zones around Mesopotamia (following a kind of transhumance).

Clay was not the sole building material: some structures were built in stone, notably the limestone quarried about 50 km west of Uruk (where gypsum and sandstone were also found).

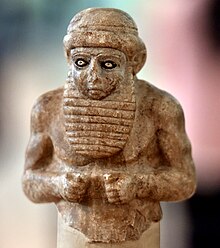

An important figure who clearly holds some kind of authority has long been noted: a bearded man with a headband who is usually depicted wearing a bell-shaped skirt or as ritually naked.

[98] Researchers who analyse the appearance of the state as being characterised by greater central control and stronger social hierarchy, are interested in the role of the elites who sought to reinforce and organise their power over a network of people and institutions and to augment their prestige.

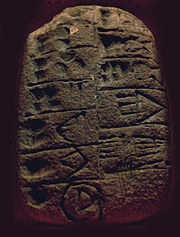

[99] With respect to this development of a more centralised control of resources, the tablets of Late Uruk reveal the existence of institutions that played an important role in society and economy and undoubtedly in contemporary politics.

One study carried out at Abu Salabikh in lower Mesopotamia indicated that the production was distributed between different households of different sizes, wealth, and power, with the large institutions at the top.

Early urbanisation should therefore be thought of as a phenomenon which took place simultaneously in several regions of the Near East in the 4th millennium BC, though further research and excavation is still required in order to make this process clearer to us.

[37][113] Urbanisation is not found everywhere in the sphere of influence of the Uruk culture; at its extreme northern edge, the site of Arslantepe had a palace of notable size but it was not surrounded by any kind of urban area.

[113][114] This model of a house with a central space remained very widespread in the cities of Mesopotamia in the following periods, although it must be kept in mind that the floor plans of residences were very diverse and depended on the development of urbanism in different sites.

[116] This, notably, allowed them to administer trading posts with precision, noting down the arrival and departure of products—sometimes presented as purchase and sale—in order to maintain an exact count of the products in stock in the storerooms which the scribe had responsibility for.

It is thought that notches would be placed on the surface of the clay balls containing the calculi, leading to the creation of numerical tablets which served as an aide-mémoire before the development of true writing (on which, see below).

These texts were misunderstood by their first publisher in the 1930s, Adam Falkenstein, and it was only through the work of the German researchers Hans Nissen, Peter Damerow and Robert Englund over the following 20 years that substantial progress was made.

[129] A more recent theory, defended by Jean-Jacques Glassner, argues that from the beginning writing was more than just a managerial tool; it was also a method for recording concepts and language (i.e. Sumerian), because from its invention the signs did not only represent real objects (pictograms) but also ideas (ideograms), along with their associated sounds (phonograms).

This realism indicates a true shift, which might be called 'humanist', because it marks a turning point in Mesopotamian art and more generally a change in the mental universe which placed man or at least the human form in a more prominent position than ever before.

A final remarkable work of the artists of Uruk III is the Mask of Warka, a sculpted female head with realistic proportions, which was discovered in a damaged state, but was probably originally part of a complete body.

[97] The religious beliefs of the 4th millennium BC have been the object of debate: Thorkild Jacobsen saw a religion focused on gods linked to the cycle of nature and fertility, but this remains very speculative.