Uruk

By the final phase of the Uruk period around 3100 BC, the city may have had 40,000 residents,[2] with 80,000–90,000 people living in its environs,[3] making it the largest urban area in the world at the time.

After the end of the Early Dynastic period, marked by the rise of the Akkadian Empire, the city lost its prime importance.

William Kennett Loftus visited the site of Uruk in 1849, identifying it as "Erech", known as "the second city of Nimrod", and led the first excavations from 1850 to 1854.

Its names in other languages include: Arabic: وركاء or أوروك, Warkāʾ or Auruk; Classical Syriac: ܐܘܿܪܘܿܟ, ʿÚrūk; Biblical Hebrew: אֶרֶךְ ʾÉreḵ; Ancient Greek: Ὀρχόη, romanized: Orkhóē, Ὀρέχ Orékh, Ὠρύγεια Ōrúgeia.

[7] The rest of the city was composed of typical courtyard houses, grouped by profession of the occupants, in districts around Eanna and Anu.

[8] This canal system flowed throughout the city connecting it with the maritime trade on the ancient Euphrates River as well as the surrounding agricultural belt.

The change in position was caused by a shift in the Euphrates at some point in history, which, together with salination due to irrigation, may have contributed to the decline of Uruk.

This period of 800 years saw a shift from small, agricultural villages to a larger urban center with a full-time bureaucracy, military, and stratified society.

Dynastic categorizations are described solely from the Sumerian King List, which is of problematic historical accuracy;[9][10] the organization might be analogous to Manetho's.

It enjoyed brief periods of independence during the Isin-Larsa period, under kings such as (possibly Ikūn-pî-Ištar, Sumu-binasa, Alila-hadum, and Naram-Sin), Sîn-kāšid, his son Sîn-irībam, his son Sîn-gāmil, Ilum-gāmil, brother of Sîn-gāmil, Etēia, AN-am3 (Dingiram), ÌR3-ne-ne (Irdanene), who was defeated by Rīm-Sîn I of Larsa in his year 14 (c. 1740 BC), Rîm-Anum and Nabi-ilīšu.

[12][11][13][14][15] It is known that during the time of Ilum-gāmil a temple was built for the god Iškur (Hadad) based on a clay cone inscription reading "For the god Iškur, lord, fearsome splendour of heaven and earth, his lord, for the life of Ilum-gāmil, king of Uruk, son of Sîn-irībam, Ubar-Adad, his servant, son of Apil-Kubi, built the Esaggianidu, ('House — whose closing is good'), the residence of his office of en, and thereby made it truly befitting his own li[fe]".

[23] Later, in the Late Uruk period, its sphere of influence extended over all Sumer and beyond to external colonies in upper Mesopotamia and Syria.

This is pointed out repeatedly in the references to this city in religious and, especially, in literary texts, including those of mythological content; the historical tradition as preserved in the Sumerian king-list confirms it.

In myth, kingship was lowered from heaven to Eridu then passed successively through five cities until the deluge which ended the Uruk period.

[27] The site, which lies about 50 miles (80 km) northwest of ancient Ur, is one of the largest in the region at around 5.5 km2 (2.1 sq mi) in area.

By Loftus' own account, he admits that the first excavations were superficial at best, as his financiers forced him to deliver large museum artifacts at a minimal cost.

It was later discovered that this 40-to-50-foot (12 to 15 m) high brick wall, probably utilized as a defense mechanism, totally encompassed the city at a length of 9 km (5.6 mi).

[33][34] Among the finds was the Stell of the Lion Hunt, excavated in a Jemdat Nadr layer but sylistically dated to Uruk IV.

The results are documented in two series of reports: Most recently, from 2001 to 2002, the German Archaeological Institute team led by Margarete van Ess, with Joerg Fassbinder and Helmut Becker, conducted a partial magnetometer survey in Uruk.

The soil characteristics of the site make ground penetrating radar unsuitable so caesium magnetometers, combined with resistivity probes, are being used.

There was an even larger cache of legal and scholarly tablets of the Neo-Babylonian, Late Babylonian, and Seleucid period, that have been published by Adam Falkenstein and other Assyriological members of the German Archaeological Institute in Baghdad as Jan J.

Archeologists have discovered multiple cities of Uruk built atop each other in chronological order.Charvát, Petr; Zainab Bahrani; Marc Van de Mieroop (2002).

The structure of the Stone Temple further develops some mythological concepts from Enuma Elish, perhaps involving libation rites as indicated from the channels, tanks, and vessels found there.

The Anu Ziggurat began with a massive mound topped by a cella during the Uruk period (c. 4000 BC), and was expanded through 14 phases of construction.

The White Temple could be seen from a great distance across the plain of Sumer, as it was elevated 21 m and covered in gypsum plaster which reflected sunlight like a mirror.

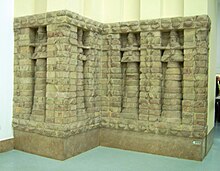

The Stone-Cone Temple, named for the mosaic of colored stone cones driven into the adobe brick façade, may be the earliest water cult in Mesopotamia.

Between these two monumental structures a complex of buildings (called A–C, E–K, Riemchen, Cone-Mosaic), courts, and walls was built during Eanna IVb.

These buildings were built during a time of great expansion in Uruk as the city grew to 250 ha (620 acres) and established long-distance trade, and are a continuation of architecture from the previous period.

Also in period IV, the Great Court, a sunken courtyard surrounded by two tiers of benches covered in cone mosaic, was built.

This period corresponds to Early Dynastic Sumer c. 2900 BC, a time of great social upheaval when the dominance of Uruk was eclipsed by competing city-states.