Ushnu

[4]: 271 [5] Notable ushnus are found in Vilcashuamán, Huánuco Pampa, Chinchero the three of them in Peru and Samaipata in Bolivia and Shincal de Quimivil in northern Argentina.

He also directed that there be a throne and seat of the Incas called usno in each uamani [district]The truncated pyramids and the circular pillar with a basin−pit system found during the archaeological surveys in Caral date back to the Andean preceramic period (8000 to 1800 BCE) and represent mountain and water cult symbols.

He climbed it and could spot a multitude of Incan soldier in the fields, thus he ordered his four small cannons to be hidden on the top of the fortress to get ready for the attack.

Other images of ushnu platforms are found in the drawings and books by 19th century explorers such as Léonce Angrand (1874)[14] Ephraim George Squier (1877),[15] and Charles Wiener (1880).

When the ushnus were built in the new conquered areas, where they adopted the physical form of platforms or pyramids, a drainage was emplaced together with a stairway and in some cases a seat on the top.

On the contrary the natural carved stone may have very different shapes depending on the original rock outcrop, with one common point: the seat or throne on top of it.

Thus the Sapa Inca or his representative, on top of the ushnu, was seating in a central position connecting all the sacred ceques directions.

[2]: 354–356 [35] The ushnu as a well recognizable character of Inca architecture represented one of the main symbols of the central power in peripheral settlements and administrative centers.

As a sort of theatricality of power the ushnu was intended to produce a uniform collective consciousness that allowed all person subjected to the Inca to feel connected to the astral deities and to the sacred places.

This was primarily intended to ensure ideological domination over the multitudes of newly subjugated peoples in the recently conquered territories.

Several have been restored and others are being considered for further research especially under the Proyecto Qhapaq Ñan carried out by the Ministerio de Cultura (Ministry of Culture) in Peru.

[2]: 357 … in the large plaza of the city of Cuzco, there stood the stone of the war that was large, in the shape and make of a sugarloaf, well stuck and filled with gold ...In 1534 Pizarro, after conquering Cusco, decided to convert it into a Spanish colonial town, to this purpose he reserved areas to the east and the south of the square for the erection of the new cathedral and the Jesuits' church.

These steps were most probably the foundation of the Cusco ushnu and its destruction and substitution for a gibbet was a sign of the empowerment of the new governor and of the end of the Inca sacred ceremonies.

Thus, Guamán Poma de Ayala[13]: plate398 draws the ushnu of Cuzco as superimposed platforms, like a truncated pyramid, on top of which Manco Inca Yupanqui (founder and monarch of the independent Neo-Inca State in Vilcabamba) sits.

This system was composed of a series of ritual imaginary pathways leading outward from Cusco into the territory of the Inca Empire.

All along the ceque lines huacas (shrines, sacred places) were found corresponding to spots of ceremonial, ritual, or religious significance.

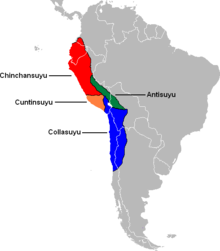

The first huaca of the fifth ceque of Antisuyu was in the main square and was mentioned as usnu by Polo de Ondegardo (Spanish colonial jurist, civil servant and thinker).

Notably the southern direction of its stairway was possibly oriented to the 6,635 metres (21,768 ft) high, permanently snow-capped Yerupajá, which was a very important apu (protective deity of the mountains).

The public activities that were carried out around the ushnu of Huánuco Pampa constituted, possibly, a symbolic way of rewarding the attending people through the libation rituals.

[5] The area was conquered by the Incas to gain access to the forested lowlands and the coca plantations, when they expanded their empire towards the east in the current Santa Cruz Department (Bolivia).

[48]: 191 In fact the south side of the outcrop shows five sculpted seats from which persons may have observed the events taking place in the plaza.

[6] This assumption is quite complex because the rock has seats and niches facing different cardinal points and only a few of them could have been used as ushnu for rituals to be kept in the plaza which remains quite far away.

The archaeological investigations, started in 1901, revealed ancient buildings, out of which about one hundred can be found today, that were part of the Inca settlement.

The settlement had a plaza, five kallankas (halls) a 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) long aqueduct to provide fresh water, and about twenty collcas (warehouses).

It has an access through the west side front, formed by a stone stairway with 9 steps, which leads to a trapezoidal opening placed in the center of the façade.

A bench with stone walls filled with mortar and a seat made of flat slates can be observed on the northern sector of the platform.

Before their placement, the stones underwent rudimentary percussion work in order to adapt them to imitate the typical Cusco stonework.