Usury

[4] Similar condemnations are found in religious texts from Buddhism, Judaism (ribbit in Hebrew), Christianity, and Islam (riba in Arabic).

Usury (in the original sense of any interest) was denounced by religious leaders and philosophers in the ancient world, including Moses,[7] Plato, Aristotle, Cato, Cicero, Seneca,[8] Aquinas,[9] Gautama Buddha[10] and Muhammad.

The historian Paul Johnson comments: Most early religious systems in the ancient Near East, and the secular codes arising from them, did not forbid usury.

[13]Theological historian John Noonan argues that "the doctrine [of usury] was enunciated by popes, expressed by three ecumenical councils, proclaimed by bishops, and taught unanimously by theologians.

In 1275, Edward I of England passed the Statute of the Jewry which made usury illegal and linked it to blasphemy, in order to seize the assets of the violators.

[20] The rich who were in a position to take advantage of the situation became the moneylenders when the increasing tax demands in the last declining days of the Empire crippled and eventually destroyed the peasant class by reducing tenant-farmers to serfs.

[21] Cicero, in the second book of his treatise De Officiis, relates the following conversation between an unnamed questioner and Cato: ...of whom, when inquiry was made, what was the best policy in the management of one's property, he answered "Good grazing."

[32]Johnson contends that the Torah treats lending as philanthropy in a poor community whose aim was collective survival, but which is not obliged to be charitable towards outsiders.

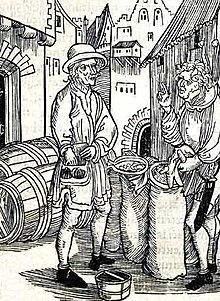

[33]As Jewish people were ostracized from most professions by local rulers during the Middle Ages, the Western churches and the guilds,[34] they were pushed into marginal occupations considered socially inferior, such as tax and rent collecting and moneylending.

For instance, the 15th-century commentator Rabbi Isaac Abarbanel specified that the rubric for allowing interest does not apply to Christians or Muslims, because their faith systems have a common ethical basis originating from Judaism.

xviii, 8], and in lending money ask the hundredth of the sum [as monthly interest], the holy and great Synod thinks it just that if after this decree any one be found to receive usury, whether he accomplish it by secret transaction or otherwise, as by demanding the whole and one half, or by using any other contrivance whatever for filthy lucre's sake, he shall be deposed from the clergy and his name stricken from the list.

(canon 25)[45] [emphasis in source]The Council of Vienne made the belief in the right to usury a heresy in 1311, and condemned all secular legislation that allowed it.

We, therefore, wishing to get rid of these pernicious practices, decree with the approval of the sacred council that all the magistrates, captains, rulers, consuls, judges, counsellors or any other officials of these communities who presume in the future to make, write or dictate such statutes, or knowingly decide that usury be paid or, if paid, that it be not fully and freely restored when claimed, incur the sentence of excommunication.

[47]The Fifth Lateran Council, in the same declaration, gave explicit approval of charging a fee for services so long as no profit was made in the case of Mounts of Piety: (...) We declare and define, with the approval of the Sacred Council, that the above-mentioned credit organisations, established by states and hitherto approved and confirmed by the authority of the Apostolic See, do not introduce any kind of evil or provide any incentive to sin if they receive, in addition to the capital, a moderate sum for their expenses and by way of compensation, provided it is intended exclusively to defray the expenses of those employed and of other things pertaining (as mentioned) to the upkeep of the organizations, and provided that no profit is made therefrom.

It certainly should not be considered as usurious; (...)[47]Pope Sixtus V condemned the practice of charging interest as "detestable to God and man, damned by the sacred canons, and contrary to Christian charity.

In condemning usury Aquinas was much influenced by the recently rediscovered philosophical writings of Aristotle and his desire to assimilate Greek philosophy with Christian theology.

The Catholic Church, in a decree of the Fifth Council of the Lateran, expressly allowed such charges in respect of credit-unions run for the benefit of the poor known as "montes pietatis".

Pope Benedict XIV's encyclical Vix Pervenit (1745), operating in the pre-industrial mindset[neutrality is disputed] [original research?

[64]He further gave the following view of the development of Catholic practice: In such a situation the legislator has to choose between forbidding interest here and allowing usury there; between restraining speculation and licensing oppression.

[64]The Congregation of the Missionary Sons of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, a Catholic Christian religious order, teaches that the charging of interest is sinful[citation needed].

Charging interest is indeed sinful when doing so takes advantage of a person in need as well as when it means investing in corporations involved in the harming of God's creatures.

(See Islamic banking) The following quotations are English translations from the Qur'an:[65] Those who consume interest will stand (on Judgment Day) like those driven to madness by Satan’s touch.

(Al-'Imran 3:130) We forbade the Jews certain foods that had been lawful to them for their wrongdoing, and for hindering many from the Way of Allah, taking interest despite its prohibition, and consuming people’s wealth unjustly.

The attitude of Muhammad to usury is articulated in his Last Sermon:[66]Verily your blood, your property are as sacred and inviolable as the sacredness of this day of yours, in this month of yours, in this town of yours.

Interest on loans, and the contrasting views on the morality of that practice held by Jews and Christians, is central to the plot of Shakespeare's play The Merchant of Venice.

Shakespeare's play is a vivid portrait of the competing views of loans and use of interest, as well as the cultural strife between Jews and Christians that overlaps it.

In the early 20th century Ezra Pound's anti-usury poetry was not primarily based on the moral injustice of interest payments but on the fact that excess capital was no longer devoted to artistic patronage, as it could now be used for capitalist business investment.

[83] In the 1996 Smiley v. Citibank case, the Supreme Court further limited states' power to regulate credit card fees and extended the reach of the Marquette decision.

[84] Some members of Congress have tried to create a federal usury statute that would limit the maximum allowable interest rate, but the measures have not progressed.

[89][90] The decline of the Byzantine Empire led to a growth of capital in Europe, so the Catholic Church tolerated zinskauf as a way to avoid prohibitions on usury.