Utagawa Toyoharu

Born in Toyooka in Tajima Province,[1] Toyoharu first studied art in Kyoto, then in Edo (modern Tokyo), where from 1768 he began to produce designs for ukiyo-e woodblock prints.

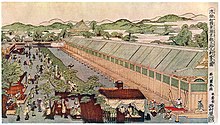

He soon became known for his uki-e "floating pictures" of landscapes and famous sites, as well as copies of Western and Chinese perspective prints.

The Utagawa school of art grew to dominate ukiyo-e in the 19th century with artists such as Utamaro, Hiroshige, and Kuniyoshi.

Tradition holds that the name Utagawa derives from Udagawa-chō, where Toyoharu lived in the Shiba district in Edo.

[3] He died in 1814 and was buried in Honkyōji Temple in Ikebukuro under the Buddhist posthumous name Utagawa-in Toyoharu Nichiyō Shinji (歌川院豊春日要居士).

[b][11] Toyoharu's works have a gentle, calm, and unpretentious touch,[4] and display the influence of ukiyo-e masters such as Ishikawa Toyonobu and Suzuki Harunobu.

[14] One of the better-known examples of Toyoharu's work in this style is a four-sheet set depicting the Chinese ideal of the four arts.

[4] Toyoharu produced a small number of yakusha-e actor prints that, in contrast to the works of the leading Katsukawa school, are executed in the learned style of an Ippitsusai Bunchō.

[4] While Toyoharu trained in Kyoto he may have been exposed to the works of Maruyama Ōkyo, whose popular megane-e were pictures in one-point perspective meant to be viewed in a special box in the manner of the French vue d'optique.

These early examples were inconsistent in their application of perspective techniques, and the results can be unconvincing; Toyoharu's were much more dextrous,[17] though not strict—he manipulated it to allow the representation of figures and objects that otherwise would have been obscured.

The titles were often fictional: The Bell which Resounds for Ten Thousand Leagues in the Dutch Port of Frankai is an imitation of a print of the Grand Canal of Venice from 1742 by Antonio Visentini, itself based on a painting by Canaletto.

Excepting a few prominent examples, such as Hiroshige or Kuniyoshi, the later generations of artists tended to lack stylistic diversity, and their work has become emblematic of ukiyo-e's decline in the 19th century.