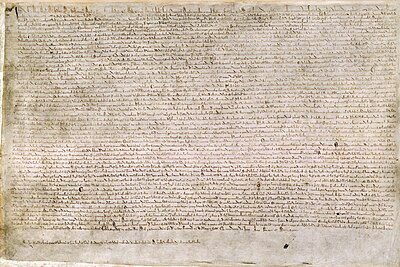

Vellum

Modern scholars and experts often prefer to use the broader term "membrane", which avoids the need to draw a distinction between vellum and parchment.

[4] Vellum is generally smooth and durable, but there are great variations in its texture which are affected by the way it is made and the quality of the skin.

The making involves the cleaning, bleaching, stretching on a frame (a "herse"), and scraping of the skin with a crescent-shaped knife (a "lunarium" or "lunellum").

Scratching the surface with pumice, and treating with lime or chalk to make it suitable for writing or printing ink can create a final look.

[5][6][7] Though Christopher de Hamel, an expert on medieval manuscripts, writes that "for most purposes the words parchment and vellum are interchangeable",[8] a number of distinctions have been made in the past and present.

Calf, sheep, and goat were all commonly used, and other animals, including pig, deer, donkey, horse, or camel were used on occasion.

"[11] Writing in 1936, Lee Ustick explained that: To-day the distinction, among collectors of manuscripts, is that vellum is a highly refined form of skin, parchment a cruder form, usually thick, harsh, less highly polished than vellum, but with no distinction between skin of calf, or sheep, or of goat.

[13] In the usage of modern practitioners of the artistic crafts of writing, illuminating, lettering, and bookbinding, "vellum" is normally reserved for calfskin, while any other skin is called "parchment".

Historians have found evidence of manuscripts where the scribe wrote down the medieval instructions now followed by modern membrane makers.

Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham point out, in their Introduction to Manuscript Studies, that "the quire was the scribe's basic writing unit throughout the Middle Ages".

Vellum can be stained virtually any color but seldom is, as a great part of its beauty and appeal rests in its faint grain and hair markings, as well as its warmth and simplicity.

Lasting in excess of 1,000 years—for example, Pastoral Care (Troyes, Bibliothèque Municipale, MS 504), dates from about 600 and is in excellent condition—animal vellum can be far more durable than paper.

[19] In February 2016, the UK House of Lords announced that legislation would be printed on archival paper instead of the traditional vellum from April 2016.

[21] On 2017, the House of Commons Commission agreed that it would provide front and back vellum covers for record copies of Acts.

[23] The only UK company still producing traditional parchment and vellum is William Cowley (established 1870), which is based in Newport Pagnell, Buckinghamshire.

Its dimensions are more stable than a linen or paper sheet, which is frequently critical in the development of large scaled drawings such as blueprints.