Uti possidetis

A peace treaty was presumed to give each party a permanent right to the territory it occupied at the conclusion of hostilities, unless the contrary was expressly stipulated.

When colonial territories achieve independence, or when a polity breaks up (e.g., Yugoslavia), then, in default of a better rule, the old administrative boundaries between the new states ought to be followed.

However, in reality proof of ownership could be exceedingly difficult[1] for lack of documentation since, during the formative period of Roman law, there was no system of written conveyancing and registration of land.

A praetor held office for a year, at the start of which it was customary for him to publish edicts; these announced the legal policies he intended to apply.

[7] According to the Roman jurist Gaius (Institutes, Fourth Commentary): *The vindication was the name of the traditional action for claiming ownership of land, as already explained.

[14] This was significant when early modern European powers sought to apply the uti possidetis concept to their colonial acquisitions (see below).

Accordingly, on a prearranged day the parties would commit a symbolic act of violence (vis ex conventu)[18] e.g. pretending to expel each other from the land.

[19] The agere per sponsonie was sent off to be tried by a iudex (akin to a one-man jury, usually a prominent citizen),[20] who in due course delivered his decision.

[21] Meanwhile, the right to interim possession of the land was auctioned to whichever of the two contestants was the highest bidder, on his promise to pay his adversary the rent if he turned out to be in the wrong.

Getting one's opponent into court at all could be difficult, and arguably praetors "were nothing more than politicians, frequently incompetent, open to bribery, and largely insulated against suits for malfeasance".

The Roman doctrine about establishing possession (not ownership) may seem slightly elusive for those brought up in the Anglophone common law[24] where it is trivially obvious that a good title to land can indeed be acquired by mere occupation (e.g. "squatters' rights").

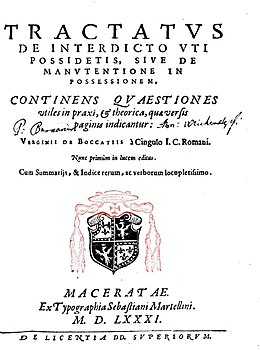

Although Gaius' text was imperfectly known to early modern Europeans, because it was lost and not rediscovered until 1816,[26] they knew the edict in the later recension by Justinian.

De cloacis hoc interdictum non dabo: neque pluris quam quanti res elit; intra annum, quo primum experiundi potestas fuerit, agere permittan.

The value of the thing in dispute and no more may be recovered, and I will not allow a party to proceed in this way except within the first year of days available for procedure (annus utilis).

[30][31][32] European powers, when they sought to justify their acquisition of territory in America and elsewhere, based their claims on a variety of legal concepts.

But some prominent European jurists and theologians, like Francisco de Vitoria, rejected this, arguing that the lands did have owners: the indigenous peoples.

[40] As the new continent was explored it was gradually realised that the Tordesillas line, though rather vague,[41] gave Portugal only a corner of it, the vast majority going to Spain.

Summarised E. Bradford Burns: From a few village nuclei and plantations in the mid-sixteenth century clinging tenuously to the shores of the South Atlantic Ocean, first the Luso-Brazilians and, after 1822, the Brazilians crept westward and northwestward to the foothills of the mighty Andes Mountains by 1909.

Thus, by mid 17th century – see map (a) – the Portuguese had established incursive footholds around the mouth of the Amazon and along the south Atlantic coast.

[42] Modern research has revealed that their cartographers deliberately distorted maps to convince the Spanish they occupied more land to the east than was the case.

[54][55][56] By 1750, the Luso-Brazilians, employing their "indirect method of conquest", had tripled the extension of Portuguese America beyond that allowed by the Treaty of Tordesillas.

In the Portuguese view this trumped Spanish paper claims – such as, under the Treaty of Tordesillas – because, as time went by, they became obsolete and no longer reflected reality.

[60] In The Undrawn Line: Three Centuries of Strife on the Paraguayan-Mato Grosso Frontier, John Hoyt Williams wrote: When the Treaty of Madrid was signed in 1750, separating the Spaniards and Portuguese from each other's throats, it established the high-minded principle of uti possidetis as a basis of territorial settlement.

Intended to be an even-handed manner of recognizing the territory actually held (rather than merely claimed) by each of the contestants, in reality it touched off complex and bitter maneuvers to grab as much of the unmapped wilderness as possible before demarcation teams could arrive and begin to plot precise imperial limits.

[65] In treaties between Brazil and (respectively) Uruguay (1851), Peru (1852), Venezuela (1852), Paraguay (1856), the Argentine Confederation (1857), and Bolivia (1867), the uti possidetis de facto principle was adopted.

When two states had been at war, the ensuing peace treaty was interpreted to mean that each party got a permanent right to the territory it occupied at the conclusion of hostilities, unless the contrary was expressly stipulated.

Probably the most influential 19th century textbook, Henry Wheaton's Elements of International Law, asserted (in text virtually unchanged through successive editions for 80 years):[67] The treaty of peace leaves everything in the state in which it found it – according to the principle of uti possidetis – unless there be some express stipulation to the contrary.

In such cases it was doubtful whether the losing side was deemed (1) to assert the status quo ante bellum or (2) to concede the uti possidetis, but most authors favoured the latter alternative.

[69] The classical doctrine that victory in war gave good title to conquered territory was modified in the 20th century.

[74] Later, the principle was extended to the newly independent African states, and it has been applied to the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union.