Spanish American wars of independence

[39] By desacralizing power and frontal attacks on the clergy, the crown, according to William B. Taylor, undermined its own legitimacy, since parish priests had been traditionally the "natural local representatives of their Catholic king.

[28] This resulted in their taking action by using their wealth and positions within society, often as leaders within their communities, to spur resistance to convey their displeasure with Spanish reforms because of the negative economic impact which they had.

Following traditional Spanish political theories on the contractual nature of the monarchy (see Philosophy of Law of Francisco Suárez), the peninsular provinces responded to the crisis by establishing juntas.

These kingdoms were defined as "the viceroyalties of New Spain (Mexico), Peru, New Granada, and Buenos Aires, and the independent captaincies general of the island of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guatemala, Chile, Province of Venezuela, and the Philippines.

On the other hand, royal officials and Spanish Americans who desired to keep the empire together were split between liberals, who supported the efforts of the Cortes, and conservatives (often called "absolutists" in the historiography), who did not want to see any innovations in government.

Finally, although the juntas claimed to carry out their actions in the name of the deposed king, Ferdinand VII, their creation provided an opportunity for people who favored outright independence to promote their agenda publicly and safely.

A similar tension existed in Venezuela, where the Spanish immigrant José Tomás Boves formed a powerful, though irregular, royalist army out of the Llaneros, mixed-race slave and plains people, by attacking the white landowning class.

Finally, in the back country of Upper Peru, the republiquetas kept the idea of independence alive by allying with disenfranchised members of rural society and native groups, but were never able to take the major population centers.

Increasingly violent confrontations developed between Spaniards and Spanish Americans, but this tension was often related to class issues or fomented by patriot leaders to create a new sense of nationalism.

In Venezuela during his Admirable Campaign, Simón Bolívar instituted a policy of a war to the death, in which royalist Spanish Americans would be purposely spared but even neutral Peninsulares would be killed, to drive a wedge between the two groups.

The Venezuelan Llaneros switched to the patriot banner once the elites and the urban centers became securely royalist after 1815, and it was the royal army in Mexico that ultimately brought about that nation's independence.

[65] Philosophers Works At the first years of war, during Spanish constitutional period, the main military effort of Spain was aimed at preserving the island of Cuba and the viceroyalty of Mexico in North America.

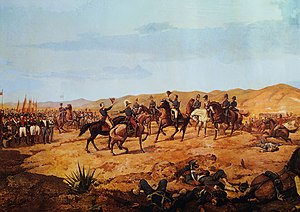

In northern South America, New Granadan and Venezuelan patriots, under leaders such as Simón Bolívar, Francisco de Paula Santander, Santiago Mariño, Manuel Piar and José Antonio Páez, carried out campaigns in the vast Orinoco River basin and along the Caribbean coast, often with material aid coming from Curaçao and Haiti.

But once in Spain he realized that he had significant support from conservatives in the general population and the hierarchy of the Spanish Catholic Church; so, on 4 May, he repudiated the Constitution and ordered the arrest of liberal leaders on 10 May.

In fact, in areas of New Spain, Central America and Quito, governors found it expedient to leave the elected constitutional ayuntamientos in place for several years to prevent conflict with the local society.

[73] In northern South America, after several failed campaigns to take Caracas and other urban centers of Venezuela, Simón Bolívar devised a similar plan in 1819 to cross the Andes and liberate New Granada from the royalists.

Like San Martín, Bolívar personally undertook the efforts to create an army to invade a neighboring country, collaborated with pro-independence exiles from that region, and lacked the approval of the Venezuelan congress.

Unlike San Martín, however, Bolívar did not have a professionally trained army, but rather a quickly assembled mix of Llanero guerrillas, New Granadan exiles led by Santander and British recruits.

From June to July 1819, using the rainy season as cover, Bolívar led his army across the flooded plains and over the cold, forbidding passes of the Andes, with heavy losses—a quarter of the British Legion perished, as well as many of his Llanero soldiers, who were not prepared for the nearly 4,000-meter altitudes—but the gamble paid off.

[76] In effect, the Spanish Constitution of 1812 adopted by the Cortes of Cádiz served as the basis for independence in New Spain and Central America, since in both regions it was a coalition of conservative and liberal royalist leaders who led the establishment of new states.

This alliance coalesced towards the end of 1820 behind Agustín de Iturbide, a colonel in the royal army, who at the time was assigned to destroy the guerrilla forces led by Vicente Guerrero.

The simple terms that Iturbide proposed became the basis of the Plan of Iguala: the independence of New Spain (now to be called the Mexican Empire) with Ferdinand VII or another Bourbon as emperor; the retention of the Catholic Church as the official state religion and the protection of its existing privileges; and the equality of all New Spaniards, whether immigrants or native-born.

José de San Martín and Simón Bolívar inadvertently led a continent-wide pincer movement from southern and northern South America that liberated most of the Spanish American nations on that continent.

After securing the independence of Chile in 1818, San Martín concentrated on building a naval fleet in the Pacific to counter Spanish control of those waters and reach the royalist stronghold of Lima.

During the next few months, successful land and naval campaigns against the royalists secured the new foothold, and it was at Huacho that San Martín learned that Guayaquil (in Ecuador) had declared independence on 9 October.

[85] In Peru, on 29 January 1821, Viceroy Pezuela was deposed in a coup d'état by José de la Serna, but it would be two months before San Martín moved his army closer to Lima by sailing it to Ancón.

[86] To ensure that the Presidency of Quito became a part of Gran Colombia and did not remain a collection of small, divided republics, Bolívar sent aid in the form of supplies and an army under Antonio José de Sucre to Guayaquil in February 1821.

In 1827 Colonel José Arizabalo started an irregular war with Venezuelan guerrillas, and Brigadier Isidro Barradas led the last attempt with regular troops to reconquer Mexico in 1829.

The increasing irrelevance of the Holy Alliance after 1825 and the fall of the Bourbon dynasty in France in 1830 during the July Revolution eliminated the principal support of Ferdinand VII in Europe, but it was not until the king's death in 1833 that Spain finally abandoned all plans of military reconquest, and in 1836 its government went so far as to renounce sovereignty over all of continental America.

The arrival of the Russian fleet in Cadiz in February 1818 was not to the liking of the Spanish navy, which was dissatisfied with the state of deterioration in which some supposedly new ships were found: between 1820 and 1823 all the Warships were scrapped as being useless.