Kingdom of Valencia

It was dissolved, alongside the other components of the old crown of Aragon, by Philip V of Spain in 1707, by means of the Nueva Planta decrees, as a result of the Spanish War of Succession.

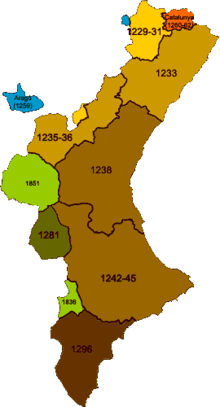

The conquest of what would later become the Kingdom of Valencia started in 1232 when the king of the Crown of Aragon, James I, called Jaume I el Conqueridor (the Conqueror), took Morella, mostly with Aragonese troops.

The matter of the large majority of Mudéjar (Muslim) population, left behind from the progressively more southern combat front, lingered from the very beginning until they finally were expelled en masse in 1609.

Up to that moment, they represented a complicated issue for the newly established Kingdom, as they were essential to keep the economy working due to their numbers, which inspired frequent pacts with local Muslim populations, such as Mohammad Abu Abdallah Ben Hudzail al Sahuir, allowing their culture various degrees of tolerance but, on the other side, they were deemed as a menace to the Kingdom due to their lack of allegiance and their real or perceived conspiracies to bring the Ottoman Empire to their rescue.

During the second revolt, king James I was almost killed in battle, but Al-Azraq also was finally subjugated, his life spared only because of a longtime relationship with the Christian monarch.

His campaign aimed at the fertile countryside around Murcia and the Vega Baja del Segura whose local Muslim rulers were bound by pacts with Castile and governing by proxy on behalf of this kingdom; Castilian troops often raided the area to assert a sovereignty which, in any case, was not stable but was characterized by the typical skirmishes and ever changing alliances of a frontier territory.

The campaign under James II was successful to the point of extending the limits of the Kingdom of Valencia well south of the previously agreed border with Castile.

Taking into account the standards of the day, it can be considered as a rather rapid conquest, since most of the territory was gained in less than fifty years and the maximum expansion was completed in less than one century.

Modern historiography sees the conquest of Valencia in the light of similar Reconquista efforts by the Crown of Castile, i.e., as a fight led by the king in order to gain new territories as free as possible of a serfdom subject to the nobility.

Finally the Aragonese nobles were granted several domains, but they managed to obtain only the interior lands, mostly mountainous and sparsely populated parts of the Kingdom of Valencia.

These facts had linguistic consequences, which are traditionally sketched this way: A few authors have promoted an alternative view, in which the languages of the conquerors were mixed with a local Romance (Mozarabic) which was already similar to Catalan.

The local industry, especially textile manufactures, achieved great development and the city of Valencia turned into a Mediterranean trading emporium where traders from all Europe worked.

The kings of Habsburg Spain (January 23, 1516 – November 1, 1700) maintained the privileges and liberties of the territories and cities which formed the kingdom and its legal structure and factuality remained intact.

Aside from economic resentment of the aristocracy, the revolt also featured a strong anti-Muslim aspect, as the superstitious populace blamed Muslims for a plague that struck the city.

The mudéjars (Muslims) were seen as allies of the aristocracy, as they worked in the nobility's large farms and undercut the Valencians on wages making them competitors for scarce jobs.

In line with similar processes in other parts of feudal Europe, the power vacuum left by rapid socio-economic change was readily filled by an increasingly emboldened monarchy.