Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel

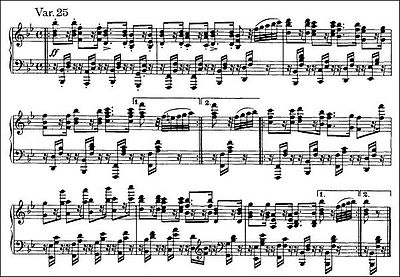

It consists of a set of twenty-five variations and a concluding fugue, all based on a theme from George Frideric Handel's Harpsichord Suite No.

[1] Biographer Jan Swafford describes the Handel Variations as "perhaps the finest set of piano variations since Beethoven", adding, "Besides a masterful unfolding of ideas concluding with an exuberant fugue with a finish designed to bring down the house, the work is quintessentially Brahms in other ways: the filler of traditional forms with fresh energy and imagination; the historical eclectic able to start off with a gallant little tune of Handel's, Baroque ornaments and all, and integrate it seamlessly into his own voice, in a work of massive scope and dazzling variety.

The Handel Variations were written in September 1861 after Brahms, aged 28, abandoned the work he had been doing as director of the Hamburg women's choir (Frauenchor) and moved out of his family's cramped and shabby apartments in Hamburg to his own apartment in the quiet suburb of Hamm, initiating a highly productive period that produced "a series of early masterworks".

24, Brahms did a careful study of "more rigorous, complex and historical models, among others preludes, fugues, canons and the then obscure dance movements of the Baroque period.

Identifying the bass as the essence of the theme ... Brahms advocated using it to control the structure and character of individual variations and of the entire set.

Because the theme for the Handel variations originated in the Baroque era, Brahms included forms such as a siciliana, a musette, a canon and a fugue.

He wrote to Breitkopf & Härtel, "I am unwilling, at the first hurdle, to give up my desire to see this, my favourite work, published by you.

1 in B♭ Major, HWV 434 (Suites de pièces pour le clavecin, published by J. Walsh, London 1733 with five variations).

[11] The appeal of the aria for Brahms might have been its simplicity: its range is restricted to one octave; the harmony is plain, with every note taken from the B-flat major scale; it "made an admirably neutral starting-place".

Brahms's use of Handel exemplifies his love of the music of the past and his tendency to incorporate it and transform it in his own compositions.

"Brahms might well have known that large and often admirable work, published as recently as 1856, which Volkmann based on the so-called 'Harmonious Blacksmith' theme from the Air with Variations in Handel's E major Harpsichord Suite.

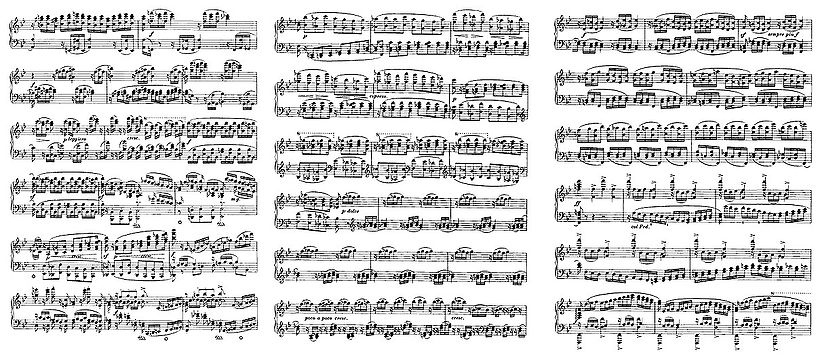

The individual variations are grouped in such a way as to create a series of waves, both in terms of tempo and dynamics, leading to the final fugue, and superimposed on this overall organization are a number of subordinate patterns.

We thus find a sensitivity to motion and momentum that complements—and possibly transcends in importance to the listener—the elegance of structure about which so many authors have (legitimately) enthused.

The elegant aria moves in stately quarter notes in 44 time with "a ceremonial character typical of its period".

Brahms's first variation stays close to the melody and harmonies of Handel's theme while changing its character completely.

While explicitly recalling the melody of Handel's theme, the chromaticism of this variation adds to the sense of a world beyond the Baroque.

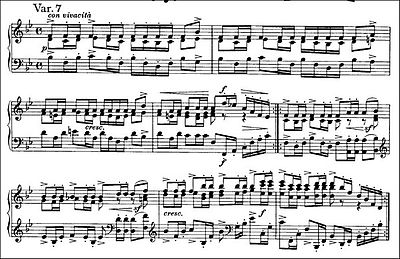

Returning to Handel's original B♭ major, Variation 7 is fast, exciting, high-spirited, and fundamentally rhythmic in nature.

A sustained drumbeat effect is created by the emphatic repetition of its upper notes and a staccato rhythm throughout all three voices.

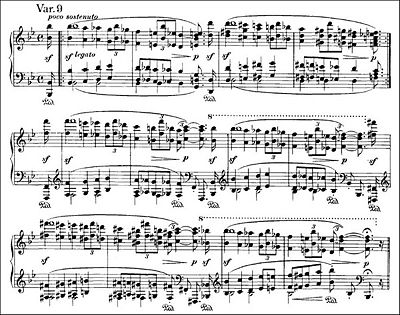

Variation 9 slows the pace of the series, with a sense of grandeur as both treble and bass move in stately, ominous octaves.

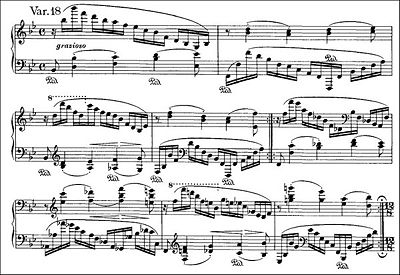

Donald Francis Tovey sees a grouping in Variations 14–18, which he describes as "aris[ing] one out of the other in a wonderful decrescendo of tone and crescendo of Romantic beauty".

The effect is of gently falling raindrops, with gracefully descending broken chords in the right hand, piano and staccato, repeated throughout the work at various pitches.

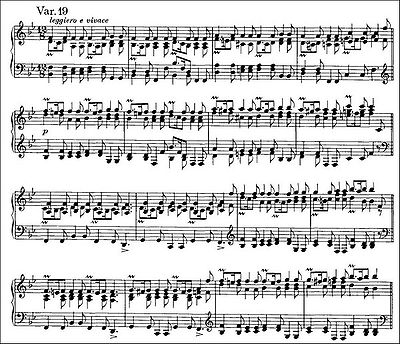

[21] The accompaniment from the previous variation, which now echoes the melody of the aria, is now syncopated and alternating between the hands, while the "raindrops" are replaced by sweeping arpeggios.

The light mood prepares the way for the climactic, concluding section which, in Tovey's words, comes "swarming up energetically out of darkness".

At its most microscopic level, the subject comes solely from the ascending major second from the first two beats in the top voice of Handel's theme.

"In this way it systematically creates a web of links between past and present, achieving synthesis rather than quotation or parody."

But the pianism is an equal part of the conception, and in this, the most complex example of Brahms's virtuoso style, the characteristic spacings in thirds, sixths and wide spans between the hands are employed as never before.

Although I can well understand this feeling, I cannot help finding it hard when one has devoted all one's powers to a work, and the composer himself has not a kind word for it.

[27] Clara Schumann premiered the work in Hamburg on December 7, when she visited Brahms's home town to give a series of performances, which also included the Piano Concerto No.

During that winter, Brahms also gave performances of the Handel Variations, as a result of which he made minor alterations to the score.

With the "complete failure,[28]" as he described it to Clara, of his first large-scale orchestral work, the First Piano Concerto, the Handel Variations became an important landmark in the developing career of Brahms.